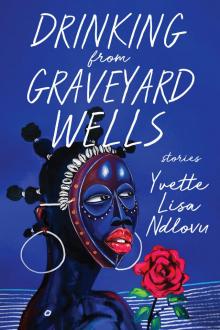

Drinking from graveyard.., p.1

Drinking from Graveyard Wells, page 1

Praise for Drinking from Graveyard Wells

“Drinking from Graveyard Wells is unlike any story collection you’ve read or will read. These wonderful, vibrant, and beautifully executed stories of life, death, and the cultural ties forged in migration have the uncanny ability to render the world we live in more intimate and mysterious than we often imagine. A striking and original debut.”

—Dinaw Mengestu, author of All Our Names, The Beautiful Things that Heaven Bears, and How to Read the Air

“In a set of short stories that skirt the surreal, the supernatural, and the mundane, Yvette Lisa Ndlovu invites readers into a look at life in Zimbabwe—past, present, and beyond. Drinking from Graveyard Wells is as mesmerizing and magical as it is unflinchingly real in its reflections, which pose questions at once personal and universal in their implications. These tales will stay with me, perhaps even haunt me, for some time to come!”

—P. Djèlí Clark, author of A Master of Djinn and Ring Shout

“Ndlovu’s stunning stories drawn from Zimbabwean and African legend poise poignant questions on history, identity, and nationhood. This is a collection by a supremely gifted writer committed to preserving and reinventing ancient folktales to weave a modern lore. She deserves nothing but the highest praise.”

—T. L. Huchu, author of The Hairdresser of Harare and The Library of the Dead

“Ndlovu’s tragicomic, sad, bold, and big-hearted Drinking from Graveyard Wells announces the arrival of a major talent. Ndlovu’s realism, both magic and hyper, spins around a central truth: amid collective peril, we need storytellers like Ndlovu all the more, those who might help spirit us into some semblance of our collective tomorrow.”

—Edie Meidav, author of Kingdom of the Young

“What a trenchant and powerful collection! These big-hearted stories offer a heady cocktail of history, myth, and realism that delights and edifies, etching women’s multicultural histories in a fresh and tender light. Ndlovu writes with sparkling wit and a keen eye for the everyday. Brimming with wisdom and intelligence, Drinking from Graveyard Wells heralds a wonderful new talent.”

—Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, author of House of Stone and I Dream America

Drinking from Graveyard Wells

Copyright © 2023 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Spalding University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, University of Pikeville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

This is a work of fiction. The characters, places, and events are either drawn from the author's imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance of fictional characters to actual living persons is entirely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ndlovu, Yvette Lisa, author.

Title: Drinking from graveyard wells : stories / Yvette Lisa Ndlovu.

Description: Lexington : The University Press of Kentucky, 2023.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022043823 | ISBN 9780813196978 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780813196992 (pdf) | ISBN 9780813196985 (epub)

Subjects: LCGFT: Short stories.

Classification: LCC PR9390.9.N4387 D75 2023 | DDC 823.92—dc23/eng/20220912

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022043823

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Member of the Association of University Presses

To my sister, Stacy, for being my first reader, role model, and rock.

And to my father, Stephen, the first storyteller in my life, who nurtured my love of reading with an unwavering belief in my impossible dreams and the magic of these stories to grow wings to carry me beyond.

Contents

Red Cloth, White Giraffe

Second Place Is the First Loser

Home Became a Thing with Thorns

The Carnivore’s Lollipop

Swimming with Crocodiles

Ugly Hamsters: A Triptych

Plumtree: True Stories

The Friendship Bench

Water Bites Back

Turtle Heart

The Soul Would Have No Rainbow

Three Deaths and The Ocean of Time

When Death Comes to Find You

Drinking from Graveyard Wells

Acknowledgments

Red Cloth, White Giraffe

On the day I die, my husband ties a red cloth on our gate. His hands are shaking. The cloth is from my favorite doek, the one that always looked like a rose when I tied it around my head on special occasions. He keeps the gates open for mourners to trickle in. The women wear black doeks, the strands of their hair tucked behind the thick cloth.

“Beauty has no place at a funeral!” Tete Saru screams at any woman who arrives uncovered. She never explains why the dead consider a woman’s hair disrespectful.

Wails and glum hymns ricochet through the house in the twilight. The red cloth marks the commencement of the all-night vigils that happen every night until I am to be buried.

There are too many people to fit into the house, so they remove the sofas from the living room and some people sit on the hardwood flooring. The sofas are carried outside, where other family members crowd around a fire, the flames casting dancing shadows. The fire burns every night before the burial. The higher the smoke rises into the air, the higher my prospects of securing a good spot amongst the ancestors.

At the first vigil, my relatives and friends argue about how the red cloth tradition started. Disputing the fabric’s origins provides a welcome distraction from the boiled cabbage swimming lifelessly on their plates. As my tete likes to remind us, eating meat at a funeral is akin to spitting in the deceased’s face.

“If you cannot forgo the luxury of meat, oil, and spice, how could you say you loved the deceased?” Tete Saru says.

Tete is in charge of inspecting the food. She urges the varoora who’d been assigned cooking duties to pour bowls and bowls of salt into the big black pots of boiling cabbage for an extra measure of misery. Funerals taste like tears and seawater.

“The red cloth has always been our culture,” a cousin says. He is an eager-eyed university student studying African History. “It signals to the community that a passing has occurred and a family is in mourning. It invites anyone, regardless of whether they knew the deceased or not, to come to pay their respects. It’s ubuntu. Even in death, I am since we are, and since we are, therefore I am.”

I wish I could smack him for sounding like a PhD dissertation and remind him of the times he ate sand, played nqobe, and did armpit farts.

“Fool!” says Sekuru Givemore, an aged uncle who’d fought in the war. “The freedom fighters during the liberation struggle started it. The white Africans, those bloody Rhodesians”—he spat on the ground after saying “Rhodesians,” as if to rid himself of the colonists along with the phlegm that had built up in his throat—“were so afraid of a revolution that they made it illegal for more than five black people who weren’t from the same household to meet under one roof. This made it complicated to bury our dead. An African must have a funeral as big as a wedding, or no funeral at all.”

“But—”

“The Rhodesians allowed funerals to happen if households would put a marker on their gates that a funeral was occurring, so that the Rhodesian Police wouldn’t disturb them as they patrolled,” my sekuru says. “That marker was the red cloth.”

“But—”

“Listen to your elders. The freedom fighters started meeting and plotting at funerals, and the Rhodesians were none the wiser. They never inspected a house with a red cloth on the gate. Thought they were clever, those bloody shits. That’s how we beat them.”

Sekuru laughs and throws a fist in the air. He starts coughing. My cousin has to slap him on the back to stop him from choking.

“It was her favorite headscarf,” my husband murmurs, but he is drowned out by another origin story.

Only Tete hears him. Her usually tough demeanor softens, and she whispers the words, “Don’t worry. We will find a way to bury her.”

The first day of being dead is a lot like sleep paralysis. I can see and hear everything around me but somehow I can’t tell my legs to move, can’t will my chest to rise or fight the pull of gravity. At first my spirit doesn’t register that its home is gone and that I must leave. I try to breathe life into the cells and jolt the heart to beat one last time. No matter how much I slap my limbs and try to pry open my eyelids, nothing moves at my command.

I remember Tete explaining death to me many years ago over a pot of cabbage. I was twelve, and it was my first funeral. My mother’s funeral.

“Westerners will tell you that funerals are for the living, not the dead, but that’s not how it works for us,” Tete Saru had said.

“What do you mean, Auntie?” I asked.

“Death is not t

She gestured for the varoora sweating over large black pots to drown the cabbage in more boiling water. The cabbage slowly turned from green to white.

“Soon you will graduate from primary school and go to high school. You will get a certificate from your school that tells the high school that you are ready for secondary education. You cannot go to high school without a certificate from your primary school. Think of death as part of a graduation ceremony at the end of mastering a long life. It is the certificate God gives you to open the gates to be with the ancestors. A spirit cannot proceed without this certificate.”

When the cabbage was sufficiently devoid of color, Tete Saru nodded her head in approval. It was ready to be served.

“One cannot skip that process,” Tete said, helping the cooks dump the soaked cabbage into plates and bowls. “You must crawl before you walk, and so the dead must be buried before they can advance to the after. The only problem with this process is that your family is in charge of securing your passage.”

My auntie’s words flood back to me as I lie in the mortuary unclaimed. Everything encasing me breaks down on a slab of steel. I yearn for a casket and fresh earth to cover me; but the dead, like newborns, are subject to the goodwill of others. My family will not bury me. The longer I stay in the mortuary, the more the gates recede.

When you’re dead, all you’re left with is your own thoughts. There is no body to distract you from yourself and no drink to fill the belly to quiet the musing. I lie in the cold that I cannot feel and think of how the end of flesh comes with an impatience, a call to journey to another world. At nine months a fetus yearns to break the barrier between the womb and a new world. I wonder if I will announce my arrival on the other side crying, too.

The third day of being dead, the sleep paralysis loosens.

The incandescent lightbulbs flicker on and off as the mortician stands over a table, working on a new body. He has the excitement and pride of a painter at a gallery showing. He likes to play with the pretty girls, girls who would never have breathed in his direction when they lived. At least other girls’ families collected them quickly.

When his fingers linger too long on the new arrival, I fight against the last hold my body has on my spirit. Something unlocks. My spirit yawns and stretches as it leaves its cage. Before I can register this new feeling, this new way of being, I hurtle towards the mortician. He yelps in surprise as his needles, scalpels, and pointy scissors fly at him. He bellows as he bleeds on the floor. I do not look back.

Newborns suck on their toes and thumbs. They don’t know what else to do in this new realm and body. I test out my new being by whipping through doors and walls. I escape from the building’s sterile walls and fly to a school playground. The children marvel at the empty swing rocking back and forth. I soon grow bored and float above the city, searching for a place to go. I see a gate with a red ribbon and race towards it.

Everyone is curious to know if they will get to attend their own funeral, but I want to know what it’s like to attend the funeral of another, as a spirit. It’s the last day of a vigil. Whoever has died will be buried tomorrow. The body rests in a coffin in the living room, sleeping one last time in its home before burial. The spirit stands over the open coffin, staring at what she once was.

“You’re . . . dead . . . too.” I try to get used to my new voice. It sounds like when the wind moans on a stormy night. “What’s your name?”

The spirit doesn’t look up. She continues to stare at her body, longing for the warmth of being alive.

“Maya.”

“Why are you upset?” I say, irritated. “At least your family is burying you!”

Her casket is completely gold. The inside has a soft white velvet lining.

“I won’t be able to cross the gates to the after,” Maya says. She points at herself in the coffin. She is wearing a pretty floral dress. That’s when I notice that she has one leg.

“I lost my leg in the car accident. I will never become an ancestor.” She weeps bitterly.

“A woman cannot proceed to the after without being whole,” I say. “That’s what Tete Saru told me.”

When I still had breath, I thought life was unfair, but death is a different kind of unfair. Spirits, especially female spirits, can be barred from the after for anything. Even women who donate their organs are not considered “whole” and cannot pass through the gates.

I fly away from the damned spirit towards home. Death is supposed to provide rest. But for Maya and me, it is just another system whose boot we live under. I throw birds at car windshields and laugh. I enter traffic lights and play with the pretty colors. I can’t tell if I like amber or green more. I avoid red. Car horns bellow as drivers swerve to avoid each other’s bumpers.

I remember the day before I died, my husband drove me to the hospital. We drove down the street lined with purple-flowered jacaranda trees as we always did. Suddenly my husband braked, nearly veering off the road. Out of nowhere a giraffe ran across the crosswalk and onto the street opposite Edgar’s department store. The shoppers inside pointed at the marvel outside. The Chipangali Wildlife Orphanage is only ten kilometers out of town, so it was nothing new for an animal to escape and make its way into rush hour traffic, blinded and scared by headlights. This giraffe in particular wasn’t spotted. It was completely white, as if it had been thrown into my auntie’s cabbage pot. A red tuft of fur clung to the base of its long neck. I don’t know why, but my hands went to the red doek tied over my hair.

“I don’t think I should go to the hospital,” I said.

“You are starting to sound like Tete Saru,” my husband said, shaking his head. “It’s rare, so what?”

“If something unexpected crosses a path you take every day,” I insisted, “you must turn back.”

“If everyone did that, no one would leave their homes,” my husband said, driving on.

Hours later the giraffe was shot, tranquilized, and airlifted back to Chipangali.

My death, like my life, was not exciting; just an incident beyond my control. Born with stubborn kidneys, I endured three weekly hospital visits for four hours. I would greet the nurse in her starched white uniform and white stockings. She would make a joke about seeing me more often than her own husband. She would weigh me, take my temperature and blood pressure, poke a needle or two and a colony of tubes into my arms. I would sit by the dialysis machine as the blood flowed into and out of my body until it was time to go home.

Kidney failure.

What a weird expression. As if my organs were students in a class competing for gold stars. My kidneys were the student that never applied himself, the student that cut class and never dreamed beyond an F.

The stats show that with dialysis treatment, patients can live a long, healthy life. These stats didn’t account for the fact that I lived in Zimbabwe. The machines are old, and the doctors and nurses were on a four-month strike before I passed. The friendly nurse left for Britain or America. I was the number, the variable the smart people didn’t account for in their studies, and so I died.

“Gone too soon” is what they call spirits like mine. Spirits that are most likely to get hung up on the injustices of their lives and become ngozi in death. “The dead must move on as the living do” is what I was taught when I was young. I don’t know if I believe in that anymore.

When I rush through my home’s gates, I find my husband pleading, begging my family to see reason.

“The mortuary fees are piling up,” he says. “How long will you keep her away from joining the ancestors?”

The men from my family do not soften.

“If you want to bury her,” they say, “finish paying for her lobola.”

“I do not have the money,” my husband says.

“She will not be buried until you do,” my family says, unwavering.

A woman has two weddings. The lobola and the white. On the morning of my lobola ceremony, a delegation from my future husband’s family made up of his brothers, uncles, and father came knocking on our gate. My father did not let them in.

“We don’t want to seem too eager,” he said, his face buried behind a newspaper. He turned the page with a flourish.