Nightmare magazine issue.., p.1

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 139 (April 2024), page 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issue 139 (April 2024)

FROM THE EDITOR

Editorial: April 2024

FICTION

My Containment

Shannon Scott

There are three children jumping over a can outside a bodega

Mark Galarrita

Backseat Kiss

James Tatam

POETRY

Ensabled Night

John R. Turner

NONFICTION

The H Word: Walking in Cemeteries

Corey Farrenkopf

De•crypt•ed: Taylor on King

Sonora Taylor

AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS

Shannon Scott

Mark Galarrita

James Tatam

MISCELLANY

Coming Attractions, May 2024

Stay Connected

Subscriptions and Ebooks

Support Us on Patreon, or How to Become a Dragonrider or Space Wizard

About the Nightmare Team

© 2024 Nightmare Magazine

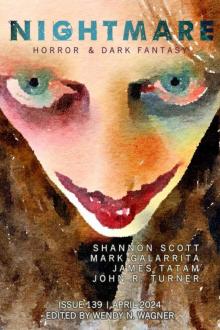

Cover by Linda Bestwick / Shutterstock Images

www.nightmare-magazine.com

Published by Adamant Press

Editorial: April 2024

Wendy N. Wagner | 314 words

Welcome to Issue #139 of Nightmare Magazine! And happy April, a month so delightful Shakespeare was both born and died in it. I like to think that if Shakespeare was working in 2024, he would be writing horror—after all, the genre is full of witches, ghosts, murder, and double-crosses, some of his favorite material.

The latter stuff—double-crossing, cheating, treachery, and betrayal—connects the work in this month’s issue. We start with a dark fantasy short by Shannon Scott: “My Containment,” a damply unpleasant little tale of a relationship based on trickery. James Tatam returns to our pages with “Backseat Kiss,” the story of a grudgingly polyamorous couple whose relationship turns horrific. Our flash piece this month is “There are three children jumping over a can outside a bodega,” by Mark Galarrita, which examines the way far too many people focus more on appearances than on real human connection. We also have a lovely poem with an unhappy ending in John R. Turner’s piece “Ensabled Night.”

Corey Farrenkopf writes about cemeteries in the latest installment of our column on horror, “The H Word,” plus we have author spotlights with our authors. In our de•crypt•ed column exploring the horror canon, Sonora Taylor discusses Stephen King’s short story “The Man Who Loved Flowers.”

I’m not going to compare the work in this issue to that of the Bard himself, but I think it’s a terrific installment in a genre that is absolutely flourishing right now. It’s said that Shakespeare lived at the very peak of the Renaissance in England, and I think it’s safe to say these writers are working at the zenith of a horror renaissance sweeping through film and literature. There’s such a tremendous amount of wonderful horror material to watch, read, and enjoy—thank you so much for spending time in our corner of the genre!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Wendy N. Wagner is the author of The Creek Girl, forthcoming 2025 from Tor Nightfire, as well as the horror novel The Deer Kings and the gothic novella The Secret Skin. Previous work includes the SF thriller An Oath of Dogs and two novels for the Pathfinder Tales series. Her short fiction has been nominated for a Shirley Jackson award, and her short stories, poetry, and essays have appeared in more than sixty venues. A Locus award nominee for her editorial work here, she also serves as the managing/senior editor of Lightspeed Magazine, and previously served as the guest editor of our Queers Destroy Horror! special issue. She lives in Oregon with her very understanding family, two large cats, and a Muppet disguised as a dog.

My Containment

Shannon Scott | 4916 words

* * *

CW: abusive relationships, implied harm to children.

* * *

When the American saw me sitting on a stone in the river, his mouth opened and closed, a brown trout caught on a fishing line. He kept his eyes on me as he hurried to pull off his socks and shoes, as if I would vanish otherwise. Then he rolled up the cuffs of his pants and waded into the shallow water. His toes were long and pale like the roots of a willow tree. When he came within arm’s reach of me, he stopped and let the current flow around his legs. He didn’t seem to know what to do.

“It’s my first time visiting the old country,” he said.

I thought he was calling me old, which I am, but not in a way he would understand.

“I’m teaching Michaelmas term at Trinity.” He grinned and nodded. “Are you familiar with Yeats?”

Maybe this is how American men seduce river women, but it’s not typical in my country. In my old country. As he continued to talk in his clipped accent, I grew bored, so I turned into a fish and swam away.

• • • •

Since I lost my sister, the days stretch ahead of me, sluggish and flat. It’s not fun to play alone. We used to take turns changing. If I became a tadpole, she became a newt, orange-bellied with sticky webbed feet. If I was a minnow, she was a dipper, a feathered fish, walking on the river floor, using her black wings to swim forward.

We were not limited to the natural world for inspiration. We could become diamond rings or porcelain teacups, plastic bags or tin cans. Treasure or trash, flotsam or forfeited.

She was better than me, I admit.

I was a silver sixpence sparkling in the water. My sister was a silver watch, intricately etched and embedded with jewels, still ticking time under the current. But I knew what people wanted to find. That was my gift. My sister’s was for detail, mine was for desire.

• • • •

The moon was as dark as the eye of an otter before the American came again. I watched him skid awkwardly down the riverbank, a bouquet of purple loosestrifes in one hand. He was growing a beard which suited him. He didn’t speak about his country or my country, but instead spoke a language we both preferred, so I didn’t swim away. Not that time. Or the time after. Or even when the weather grew cold and swans called out in the skies above us. The moss beneath my feet remained green and the water would not freeze, so the weather was all the same to me. But his breath came out like smoke and his flesh pimpled. He shivered and clung to me for warmth in a way I did not need to cling to him.

“How does it work?” He wanted to know. “Can you leave the river?”

I shook my head. I had to stay in the water. I’m not a mermaid, I have legs, but five steps away from the river and I will dry up and blow away.

I saw it happen with my own eyes.

Last year, a child fell into the river. He hit his head on a stone and my sister saved his life. She lifted his small body from the water and carried him up the riverbank and placed him in a bed of ferns. When she turned around, her lovely legs, smooth and tinted green, started to darken and crack, the fissures deepening like the bark of an aging alder tree. Desiccation spread so fast up her thighs and chest, into her neck and face, that I barely had time to scream her name before she broke apart completely. In her final transformation, she became ash, blown away by the wind and caught in small eddies along the bank.

“You turned into a fish the first time we met,” the American said. “Can you do it again? Would you do it again for me?”

I nodded. Who else was there now? No one. I was alone. When he kissed me, his lips were cold, but his chest was warm and his heart beat hard and fast.

• • • •

The last time the American came to the river, I turned into the most beautiful fish for him. Pink and purple iridescent scales, tail like delicate lace, fins shaped into tiny hearts. A creature that would have pleased my sister. Or better yet, made her jealous.

As a fish, I could only see the surface of the water reflected above me, so I swam to the top and poked my head above the current. The American’s eyes were filled with delight. It pleased me to please him. His arm was hidden behind his back. Maybe a bouquet of marsh marigolds this time? But when he brought it forward, he wasn’t holding flowers. He was holding a net.

Before I could swim away, he scooped me up, dropped me into a plastic bag of water, and twisted it closed. The world spun and blurred. I tried and failed to get my bearings. As he climbed back up the riverbank, before he got too far away, before he climbed into his car, I should have transformed. I might have made it back to the river without turning to ash. Now I will never know if I could have been faster than my sister.

• • • •

On the long journey, I thought I would die. My belly dropped in the darkness. The plastic bag rolled and bucked. I was sick and had to stay in the sickness. I closed my eyes and went back to the river. I imagined catkins above my head, felt mud squish between my toes, heard my sister laughing, her voice so light and sweet she never startled any living creature, even the heron who waited downstream for his meals. I would never see her or the places we lived together again. I would never be able to apologize for what I had done to her.

• • • •

He released me into warm water. “There,” he said. “That’s better.”

I became a woman again, gasping as I lifted my head into the air. I sat up and took in my surroundings. I was in a porcelain tub. The American crouched nearby, turning a silver knob left and right, left and right. Each time he cranked it, something rattled in the wall.

“Old pipes.” His smile was drooping wit

My feet pressed against the bottom of the tub. It wasn’t big enough to lie down and submerge myself in. There was nowhere to swim. My view was of a closed door. I thought of reaching for the American, gripping a handful of his brown hair and pushing his head beneath the tepid water. He would thrash until he didn’t. A man in water is a fish out of water. But then where would I go? I would be stuck in this room with his rotting body.

“This is temporary,” he assured me. “I’ll find a better arrangement soon.”

I gestured at the door, made a swimming motion with my hand. He had taken me to his country, his new country, and though it was unfamiliar, I knew well enough that outside the door were rivers because I could hear their voices. They were big and foreign and wild, like him, but they would welcome me. I demanded he take me to them.

“I can’t,” he said. “Everything is frozen. You have to wait until spring.”

I slapped his face and he stepped away from me, rubbing his cheek, wounded in a way that made me even more furious.

“I love you,” he said. “I couldn’t leave you behind.”

There was a plastic curtain hanging on a rod above me and I tugged it closed and hid myself from him. Then he left and locked the door behind him.

• • • •

Alone and bored, I opened bottles of blue foam and purple gel. I ran my fingers through crystals that smelled stronger than any flower I’d ever known. Everything created bubbles that made my skin itch. I watched the bubbles swirl down the drain and refilled the tub again. And again. What else was there to do? Unclog hair from the drain? Scry? There was no need for scrying to tell my future. It was a hard lump of bright green soap.

So I pretended the running faucet was my river running, that the drip from the tap came from rain hitting rocks. I rested my head on the lip of the bathtub and stared up at the rusted showerhead, at the ceiling blooming with black mold. I talked to my sister.

Remember the time we tangled those fishermen’s lines and I swiped their beer and we swam down river and drank away the afternoon.

Remember when you turned into a toad so fat you couldn’t swim.

Into a condom wrapper.

And finally.

Why did you save the child? There were other ways.

• • • •

I could hear the American inside the house. Flipping on light switches and opening doors, rustling papers and rattling dishes. He twisted on top of his squeaky mattress at night and snored. During the day, he turned on something that played music or cheering crowds, but when he left, he turned it off again. He was gone a lot. He would call out, I’m off to work, but I couldn’t speak his language to reply. I imagined him standing in front of a classroom of other captives, droning on and on about the old country in this new country.

When he was out, I turned the knob all the way to the right and let water flow into the tub until it overflowed, cresting the edge and then spilling over the side. Water crept across the tiles, grew a little higher with each minute.

Curious about the rest of the bathroom, I quickly left the tub and splashed over to the porcelain chair. I pulled down the lever. This caused water to disappear then reappear inside the chair. I pulled the lever again and again and again. Soon, water poured out of the chair too, adding another inch to the floor. I stepped back into the tub and crouched down, my weight causing a massive surge of water to flow over the edge. I stayed like that for hours, listening to the water build, seep, and drip, drip, drip somewhere far beneath me.

When the American returned, I heard his shoes, the ones he so carefully left on the riverbank, skid across the downstairs floor. Then I heard two hard thumps. One, I imagined, as he hit the wall, the second as he landed on the floor.

“Fuck, fuck, fuck!” He cursed as he climbed the stairs towards the bathroom. He didn’t knock, just yanked the door open, and water poured out and soaked his shoes. His face was bright red as he gawped at the little bog I’d created.

“What the fuck are you doing?” he shouted. “Did you have the water on all day?” There were puddles on the tile floor, saturated towels, a gurgling porcelain chair. “I could have serious water damage. This is not funny.”

He left again, squelching down two flights of stairs. Then the water stopped. Nothing came from the tap or the chair. Not even a drip. It had all run dry.

He didn’t bother coming back into the bathroom. He banged his fist against the wall and called up from the lower floor. “The water is off. I’m leaving it off until I can trust you. I suggest you don’t pull the plug.”

• • • •

After a few days, the American turned the water back on, but he didn’t visit again for a long time. When he did, he brought a bottle of wine and two glasses, setting them gingerly on the tile floor.

“I’ve missed you,” he said. “I’m sorry we fought.”

I shrugged. I was not sorry.

“I know this isn’t ideal,” he continued. “I’m working on it.”

He took a lock of my damp hair between his fingers. I wanted to kill him, but I wondered what my sister would do. She was always the kind one. And clever. And soon I was swimming in the bathtub, having changed into a large trout, mottled with irregular brown spots, sporting sharp and spindly teeth with whiskers like a sailor lost at sea.

“You’re upset,” he said.

Upset? I thought. I had tried to flush myself down the porcelain chair half a dozen times. Upset? I lifted my fat tail from the water and slapped it down hard, spraying his trouser legs. He seized his wine and left.

• • • •

Each time the American returned I was the same ugly trout. He stopped reassuring me, stopped telling me how he would fix things.

“You’re not the only one sacrificing,” he said, his shadow looming over the cloudy water that I refused to refill anymore. “I’ve been using the bathroom at work and showering at the gym. All for you. Because this is your space now.” He reached into the stagnant water, tried to grab me, but he was no bear, and I slipped away easily. He swore and kicked the bathtub. “You spend more time in this room than my ex-wife did!”

Other times, he pleaded.

“Please, come back. If you become yourself again, I promise I’ll take you to a river. The rivers are opening now. It’s thawing. It’s spring.”

I knew full well he could put me in a plastic bag anytime he wanted and take me to a river and free me. I recognized a trick. I played plenty of my own.

And finally, to my great pleasure, he began to doubt himself.

“I know you’re not a fish,” he said, though there was a thread of uncertainty.

I made my underwater expression especially trouty, like who is this crazy man talking to a fish in his bathtub?

“You’re a woman. I know you’re a woman.” He paced the small bathroom and slammed the door open and closed several times. “Not a woman. A bitch!”

• • • •

The next time he brought flowers, red roses, which he placed in the sink. When he looked down at the tub, he cried out in horror and sunk to his knees.

“No, no, no, no,” he sobbed.

He plunged his hands into the bathtub and lifted out my fish body, which had been floating belly up in the water. He raised me into the air, still muttering no, no, no and held me for about five seconds before I jerked from his grip and dove back into the water, flashing a toothy grin.

I expected a fit of rage. Maybe even pulling the plug and killing me. Instead, he was quiet. The silence went on so long that I rose to the surface to see what he was doing. To my surprise, he was taking off his clothes. His jacket was already abandoned on the floor. Now he was unbuttoning his shirt, then pulling the undershirt over his head. He took off his belt, unzipped his pants, removed his boxers, and left the clothes in a heap on the bathmat. He climbed into the water with me and sat down, his arms around his knees, his knees to his chest. He was crying. He dropped his head and tears fell into the water.

“I thought you loved me,” he said, without looking up. “I thought you understood what I was doing when I brought you here. Now it’s too late. You’re here. In a new country. I’m sorry.”