Nightmare magazine issue.., p.1

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 138 (March 2024), page 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issue 138 (March 2024)

FROM THE EDITOR

Editorial: March 2024

FICTION

Second Deaths

Keith Rosson

A Guide to Camping in the Forest

Oyedotun Damilola Muees

Our Very Best Selves!

Fatima Taqvi

POETRY

The Let Go

E. Catherine Tobler

NONFICTION

The H Word: Scream & the Joy of Cheap Thrills

J.D. Harlock

Book Reviews: New Novels by Hand & Kiste

Adam-Troy Castro

AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS

Keith Rosson

Fatima Taqvi

MISCELLANY

Coming Attractions

Stay Connected

Subscriptions and Ebooks

Support Us on Patreon, or How to Become a Dragonrider or Space Wizard

About the Nightmare Team

© 2024 Nightmare Magazine

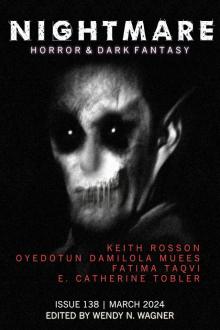

Cover by Wilqkuku / Shutterstock Images

www.nightmare-magazine.com

Published by Adamant Press

Editorial: March 2024

Wendy N. Wagner | 516 words

Welcome to Issue #138 of Nightmare Magazine. This is where I would normally say something pithy about the weather or perhaps something clever about an upcoming holiday. But instead, I’ll address a topic that’s not rooted in anything timely. In fact, it’s equally applicable across all seasons and all continents, and it’s evergreen content that goes against much of what I say and believe about humanity.

It’s this:

Sometimes people just suck.

Let me clarify. Lest you think I’ve been mainlining cable news or perhaps just reading a lot of Sartre (who hurt you, Jean-Paul, to make you say, “Hell is other people”?), I mostly believe in human goodness and expect the best from people. But I think we can all agree that when people decide to be mean, it hurts like nothing else. When a tree falls on your house, it’s scary and terrible, but you know it didn’t happen on purpose. A hurricane doesn’t pick and choose its victims. All of those terrible things? They stink, but they’re not malicious. It’s people who are.

This issue is all about things that suck. It’s about interactions gone bad, relationships that have fallen apart, and people making bad choices. That stuff is the mainstay of fiction, but this time we’re really getting into it. I’m not exactly sure what to call this bundle of bad vibes, but for better or for worse, that’s what this issue is about. That’s why we’re kicking off the month with a short story from Keith Rosson called “Second Deaths.” Keith’s work has appeared here in Nightmare before (“Primal Slap,” May 2023), but this story delves more deeply into the kind of content his novels explore—crime and poverty and just plain human nastiness. It’s a terrific story, and I hope you enjoy every gross, depressing second of it!

Fatima Taqvi’s story “Our Very Best Selves!” tilts in a very different direction. As you might guess from the title, it’s all about toxic positivity and how it helps—er, “helps”—people in difficult situations. It’s gross, too! Hooray!

Over in our Horror Lab short works, we have a delicious new poem from E. Catherine Tobler, “The Let Go,” and an uncomfortable little ghost story from Oyedotun Damilola Muees, “A Guide to Camping in the Forest.” The latest installment of our The H Word column is about the Scream franchise and what makes it so darn fun. Of course we also have spotlight interviews with our authors, and Adam-Troy Castro has some book recommendations.

It’s another terrific issue, all of it written and edited by real actual humans, not a one of whom suck. In fact, just like all of you reading this, they’re pretty delightful.

Thanks for reading (and double thanks if you have a subscription)! It’s people like you who keep me believing in this species.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Wendy N. Wagner is the author of The Creek Girl, forthcoming 2025 from Tor Nightfire, as well as the horror novel The Deer Kings and the gothic novella The Secret Skin. Previous work includes the SF thriller An Oath of Dogs and two novels for the Pathfinder Tales series. Her short fiction has been nominated for a Shirley Jackson award, and her short stories, poetry, and essays have appeared in more than sixty venues. A Locus award nominee for her editorial work here, she also serves as the managing/senior editor of Lightspeed Magazine, and previously served as the guest editor of our Queers Destroy Horror! special issue. She lives in Oregon with her very understanding family, two large cats, and a Muppet disguised as a dog.

Second Deaths

Keith Rosson | 5059 words

* * *

CW: death, bodily harm, drug abuse.

* * *

Chuck was wire-sick again, so he hobbled up onto Jerome’s porch one sunny afternoon, need curling his spine like a bent clothes hanger. Jerome was the guy who could get you whatever you needed, as long as what you needed was wire, or crank, or a pallet of Captain Chompberry cereal, or twenty cartons of stolen Lithuanian cigarettes.

It was a kind, bighearted day. The sun winked bright and lovely off all the nice things in the world, knifing him in the eyes. Chuck’s hand trembled when he knocked.

Peach, Jerome’s brother, answered the door. He was gigantic.

“What you want, man?” said Peach. His eye roved up and down through the wedge of the open door.

“It’s Chuck,” Chuck said.

Peach snorted. “I know who the fuck it is, Charles. What do you want?”

Chuck could hear Jerome, deeper in the house, asking who it was.

“It’s Charles,” Peach called back.

Chuck heard Jerome say “shit,” like he was sad to hear it.

“Come on, man,” said Chuck.

Peach sighed and opened the door. Inside, the living room was choked with gloom, only a tiny shard of sunlight falling across the floor. Piles of clothes, dirty plates, socks flung around like skinned little animals. A single piece of bread was mashed into the carpet with a shoe tread in the middle. The room brimmed with the deathly potpourri of old farts and corn chips. Jerome and Peach were playing F*ckpunch on the Xbox, and a glass bong shaped like a giant toadstool sat next to Jerome’s foot. The buzzing flies made it seem like being inside a person’s rotten brain. Chuck stood there on his ruined, throbbing feet.

Jerome stared at the TV and mashed buttons. “What do you want, Charles?” He didn’t look away from the screen.

“I need some wire,” Chuck said.

“’Course you do,” Peach said, putting his feet on the coffee table. The bottom of his socks were black with grime.

On the TV, Jerome pulled off one guy’s head and kicked it down the street like a soccer ball. Gouts of blood shot out, painting the ground, but then he had to run away because the cops came and shot at him. Chuck could see the TV screen reflected in Jerome’s eyes.

“How long you been on the wire anyway, Charles?”

“I don’t know. A while.”

“But, like, you were already a motherfucker of a certain age, right? When you started? Not like you been on it since you were fifteen or whatever, right?”

“No,” Chuck said. “I mean, yeah. You’re right.”

Peach smiled at his brother, said quietly, “He’s all fucked up.”

“How old are you, Charles?”

“Forty-eight.”

Peach’s eyes widened and he sat up on the couch and cackled. When he slapped his knee, it sounded like a pistol shot. “Forty-eight? That’s it? You’re lookin’ sixty-eight, man! Jesus!”

Chuck kept his head dipped in the necessary supplication, the requisite shame. He felt like the character in F*ckpunch, who was being harried by drone-dogs now, and lashed with whips by men in spiked leather outfits. He ran his hands down his pant legs in one big sweep of sweat and said, “You got any wire or not, Jerome? Damn.”

Jerome sighed and handed the controller to his brother. He stood up. “Don’t let my guy die.”

“Yeah, yeah,” said Peach. He had Jerome’s guy on the screen drop an old-timey anvil on a puppy and a bunch of bonus points zipped up around the mashed head.

Jerome stood there in his sweatpants, assessing Chuck and scratching at his armpit. “How’s your feet, Charles?”

“Fine.”

“He was hobbling like a bitch coming up here,” Peach said. His guy on the TV beat a policeman to death with the corpse of the dead dog. The graphics were good, amazing, realistic, horrifying, vastly, overwhelmingly different than the pixelated video games of Chuck’s boyhood.

“Let me see your hands,” Jerome said.

Chuck held out his hands, the nails whole and unbloodied.

“You just do it in your feet?”

“Yeah.”

“How much you want?”

Spit flooded Chuck’s mouth. “Three spools?”

Jerome named an amount of money that was right on the cusp of unreasonable.

Chuck, shivering, opened his wallet and handed him the money. Jerome walked down the hall and Chuck stood there watching Peach mash buttons.

The plastic baggies Jerome handed him were fogged with cold; he must keep them in a freezer somewhere. Chuck had never been able to tell the difference between cold wire and not. Everyone had an opinion on it. Crystals hung fat on the coils, big as grains of salt. Jerome had a good connection.

“Charles, you got that bi

Chuck nodded. He wanted to get out of there.

“You got that barn there?”

“Yeah.”

“Listen, how about this. I give you another spool—for nothing. For you to owe me a favor sometime.”

Even through the corkscrewing scream of his need, Chuck was suspicious. “Why?”

Jerome snorted, went to go sit on the couch. “Shit, never mind.”

“No, no,” said Chuck. “Okay.”

Jerome turned and pulled out his phone. “Give me your phone number.”

Chuck recited it to him, and Jerome texted him right there. They both heard Chuck’s phone ding in his pocket.

Jerome stood up. “When I reach out to you, Charles, you’re on board, you feel me?”

“Okay.”

Jerome went down the hall and came out with another baggie.

He handed it to Chuck. He said, “I call, you answer.”

• • • •

He drove out to the lagoon and did his business. He took his work boots off and the stink of rot filled the truck’s cab. He had yet to fix under his fingernails and told himself he never would. So far it had been true. But his feet were getting to be a problem. Not as bad as photos you could find on the internet, but the nails were peeling off in damp yellow chunks, and the toes were purple, gelatinous black blood suppurating from the flesh, the whole affair heavy with that stink of decay. Traceries of purple veins climbed his feet up to his ankles. Everything from the shins down throbbed sickly in time with his heartbeat.

After he fixed and the world softened, he put his socks back on, thinking only for a moment about driving into the lagoon, letting the brackish, silty waters overtake him.

• • • •

Krista was lying on the couch, watching TV when he got home. Her belly was starting to show beneath her I’m A Pepper Too T-shirt. She still had a while to go. Her mother, Chuck’s sister Denise, was doing ten years in Junco Bay on a big-time distribution charge, and Chuck was the only family Krista had left. She was nineteen and the dad, whoever he was, was a ghost in the wind.

He sat down in the recliner, which loosed a pained farting noise when he leaned back. He was enveloped in a quiet, wordless euphoria that threatened in its own way to overcome him. A hush and purr in his brain, the television a corona of light, Krista gilded with a kind of angelic clouding, like icing, or cotton candy.

They watched television, talking little, as the surge of the wire’s chemical euphoria slowly faded from his blood, his litany of pains slowly returning to him. It lasted less and less these days. “What kind of show is this?” he asked.

“They’re looking for ghosts.”

“They look like frat guys.”

“Yeah, they are. They challenge the ghosts to fight and go to all these haunted burial places and do keg stands and stuff. They just try to make them mad.”

“What’s the point?”

Krista didn’t answer. What was the point of anything, truly?

He fell asleep and awoke to find that she had laid a blanket over him. He needed to be on a roof in Troutdale at seven the next morning, and he closed his eyes, falling back to a dream-fogged hush.

• • • •

Two weeks later he was down to the last little curl of the last spool of wire when Jerome texted him: You home? I’m coming over.

Chuck was indeed at home. It was pissing rain outside, and his foreman had given the crew the day off. Krista was at her part-time job, cashiering at an art supply store. The house sat heavy with silence, Chuck enveloped in the morose fog that always accompanied the end of a spool.

Jerome and Peach arrived in a white Ford pickup, a horse trailer behind it. Chuck stood on the porch, motioning them toward the barn beyond the house, then put on his coat and limped after them.

Jerome stood beside the trailer, his arms crossed, a grin splitting his face. Peach sat in the driver’s seat.

“That barn locks, right?”

Chuck looked at the barn, as if it had just appeared there. Rebuilding it had been the last thing his grandfather had done to the property before he’d died seven years before. It was still in good shape.

“Yeah.”

“Good. I need you to hold something for me.”

“What?”

“My cousin,” Jerome said, and opened up the back of the trailer. Chuck could make out a crouched figure, the glitter of an eye. The serpentine slither of chains along the floor of the trailer.

Chuck heard himself say, distantly, “Why do you have your cousin chained up in a horse trailer, Jerome?”

“Well, he’s not well,” said Jerome.

“And you want him in my barn?”

Jerome slapped the side of the trailer and Peach got out of the truck. “Yeah, he doesn’t give a fuck, trust me.” Peach unhooked the eyelet of the chain that was set into the floor of the trailer and wrapped the chain around his wrist. He pulled it and Jerome’s cousin stepped out of the gloom.

He was emaciated and milk-pale. The chain connected to a collar at his throat; his hands scrabbled at it uselessly. He was shirtless. His eyes had gone vacuous, all understanding blown out of them. Both eyes covered in a milky blue haze, like cataracts.

Peach yanked on the chain, hard, and Jerome’s cousin fell in a snarling heap onto the mudded driveway, limbs starfishing as he rolled onto his back, hands still working at the chain.

“No, man,” Chuck said. He stepped back. “Sorry. You can’t keep him here.”

“Bullshit.”

“I’m serious.”

“That’s not our deal,” Jerome said, lifting his chin toward the barn. Peach started dragging his cousin along the mudded driveway.

“What’s his name,” Chuck said helplessly to Jerome’s back.

“It used to be Michael,” Jerome said over his shoulder. “Doesn’t have one anymore, though.”

Michael gagged and yanked at the chain, drawn down to this single purpose of escape. Scrabbling to his knees and falling as he was pulled along. The afternoon smelled of rain and churned mud.

Chuck trotted past them—Michael distractedly swatting at him as he passed—and unlocked the barn door. It was a dark and fusty place despite its relative newness; Chuck never came out here. The shapes of old farming equipment lay rusted and furred in cobwebs.

Peach hurled the length of chain over a rafter and grabbed it as it landed on the floor. He threw it over the rafter again, and then once more. There was a sizeable length of chain left, and Peach handed it to Chuck.

“Hold him,” he said.

He ran to the van and came back with a steel peg and a hammer, and he took the chain back from Chuck and pounded the peg through one of the chain’s links into the floor.

Chuck said, “He’s dead, right? That’s what we’re doing?” It was just a thing that happened to some people, like rosacea or being double-jointed. Uncommon but not unheard of. A death that required a second, truer, more exacting death.

Jerome reached in his pocket and handed him two spools of wire. “They’re working on shots for them, did you know that?”

“So that they can come back to life?”

Jerome laughed. “Nah, man, so that when you die, you just fucking die. None of this shit here.”

Chuck was peering down at the spools in his hand when Peach grabbed him by the wrist and stretched out his arm, twisting it taut. Then he brought the hammer down on Chuck’s elbow, pretty damn hard, just one time.

Chuck dropped the baggie and doubled over, gasping. Even through the pain he heard the hiss of the chain as Michael lurched towards him. Chuck backpedaled out of the way, still clutching his arm.

“Don’t ever tell me no again,” Jerome said as he and Peach walked out of the barn. “You think that’s a smart idea, you got a profound misunderstanding of how this all works.”

• • • •

Why wire, he sometimes wondered. What kind of lunatic had invented it? Why craft something so medieval? Something intended for pleasure? Wire under the nails? It had the cadence of torture. Torture, until it wasn’t. Until the crystals dissolved, and the world bloomed, and the darkness peeled its face back to reveal some meager but holy light, and every looming wall suddenly leaned back from you, gave you space.

Chuck had been a roofer for almost thirty years. It was work that wrecked your body. Entire days of kneeling, the bending over, the hammering on roofs at difficult angles. Killed your back, killed your knees. Chuck knew he’d be hobbled even if he didn’t wire up. He’d done everything as a younger man—coke, crank, snorted heroin, popped pills—and wire hit something in him that nothing else did. Absolved him of ownership of the terrible things. Benighted him in some arcane way. This wretched thing he did to his body, and the light just started spilling out of him.