Dance move, p.1

Dance Move, page 1

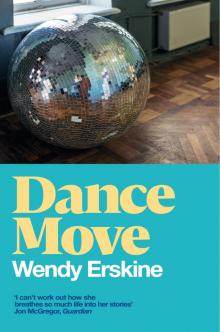

DANCE MOVE

– Stories –

Wendy Erskine

Contents

Mathematics

Mrs Dallesandro

Golem

His Mother

Dance Move

Gloria and Max

Bildungsroman

Cell

Nostalgie

Memento Mori

Secrets Bonita Beach Krystal Cancun

Man was made for Joy & Woe

And when this we rightly know

Thro the World we safely go

Joy & Woe are woven fine

A Clothing for the soul divine

—from ‘Auguries of Innocence’

by William Blake

Mathematics

The drawer beside Roberta’s bed contained remnants of other people’s fun: a small mother-of-pearl box, inlaid with gold, a lipstick that was a stripe of fuchsia, a lucky charm in the shape of a dollar sign. Anything left behind in one of the hotels had to be put in a box and kept for two months. A girl who used to live in the house told her that. Didn’t matter if it was a pair of tights or a phone charger, it was put away and then, at the end of that time, it was offered to the person who had cleaned the room where it had been found. That girl had got a little clock that way. But Mr Dalzell didn’t operate like that. Mr Dalzell had said that anything she found was hers, automatically. Finders keepers, losers weepers. Except if she found a weapon. Any guns just pass them over to me, Roberta, he laughed.

Some things didn’t make it to the drawer. Roberta would run her finger along traces of powder to see what would happen. The big flat that overlooked the river, the one with the ceiling to floor windows, was a fine spot for the powder. She often found tablets too. One lot she kept for the Saturday night when she was in her slippers and dressing gown. Her heart felt it was going to burst through her ribs. Occasionally she gave away the things she found, like the bottle of perfume that was worth over a hundred pounds. It smelled like the sawdust in a hamster’s cage. Igor took it. He puffed it on when he was dressing up for a night out. The smell hung in the hallway. But most stuff needed to be bin-bagged: dirty knickers, grey bras, empty blister packs, bottles, blades.

One time the green-door house had syringes and burnt foil everywhere. That was sad because Roberta associated the place with families, like the people who left behind a game that she tried to play. She divided herself into two teams but even though she read them a couple of times, Roberta couldn’t understand the instructions. The family left a small box of chocolates and a card on the table, saying thank you.

Roberta had encountered Mr Dalzell when the agency sent her to a restaurant for a three-day trial. The woman in charge there told her, and the other people entering the world of work, that it was important to turn up on time, dress sensibly and, most importantly, listen carefully to what they were told to do. They should take in every word and if necessary ask for clarification if they weren’t sure. On the first morning, the chef gave her an apron and told her to wash her hands. He showed her how he wanted her to cut the vegetables. She looked attentively at the way he held the knife. You think you can do that, love? he said. He let her practise with a few carrots. Then he said, see this bag of peeled spuds here? I want you to cut them just the same way. We are making a thing called dauphinoise potato. She nodded. So, love, do you think you can do that?

It hadn’t been easy to use the point of the knife to get the right small circular shape. When the chef came back he saw she had cut discs of potato the same size as the carrots. He smiled and said not to worry, that he hadn’t explained it very well, and that she should maybe polish some knives and forks. At the end of the day, he got one of the guys to show her how to mop the floor and clean the place down. That was what she was doing when Mr Dalzell came into the restaurant to sit down at a table with the owner and the chef. Now there’s a girl who knows how to work, Mr Dalzell said. She could hear the chef telling him about the potatoes. Followed instructions to the letter, he said. The total letter. Mr Dalzell surveyed the gleaming floor. How’d you like to come and work for me for a couple of weeks? he asked. But the couple of weeks had become over a year.

Mr Dalzell had provided her with training. A woman called Ava showed her how to clean the rooms, change the bedding and towels. She got to know when properties were rented by schoolkids for their parties by the pizza boxes and empty cans. She got used to the sick and even the shit. There was always the box of rubber gloves. She had got used to blood. There was one time when a laminate floor had been gluey with it. Stuck to the hall was a clump of black hair. Under the sofa she found a tooth, shreds of gum still attached. Mr Dalzell had been good to her. He owned the house where she lived. He sorted out the boys. They hung outside the shops, shouted at her, threw things. She shouted back. Listen to Crackers going crackers! they laughed. Mr Dalzell got to hear about it and then their eyes slid away from her when she walked by. One boy got a face all puffed with bruising.

Mr Dalzell got her a phone so that she could communicate with Gary Jameson. Every morning, she waited for him in the kitchen, which was always a mess. There were the plastic containers thick with the dregs of Igor’s protein shakes, the dirty dishes in the sink, the spatter of hot sauce that the girl from Donegal made down the cupboard. But she was only going to tidy things up if she was being paid. When she got into Gary Jameson’s van, he would always say the same thing: Another day, another dollar. He gave her a list of the day’s jobs and she studied it. In the back of the van there were sheets, duvet covers, pillowcases and towels, their freshness almost aggressive.

Whoever wrote the schedule knew how long each place took to be cleaned. A little flat might only be an hour. Others, like the big three-storey place, took so much longer. Gary Jameson sometimes waited outside for her, but often he went away. There were other things he needed to do in the area. Later on, he would pick up the bags of laundry and rubbish. Gary Jameson had the keys for all of the houses on a big metal ring decorated with a cockerel. Each key had a tag with the number and street name of the house. He would take off one of the keys and give it to her so she could let herself into the next place. Don’t lose it, he said. Don’t. Fucking. Lose. It.

In her little book, Roberta had all the addresses written down and all the buses she might need to get, if she couldn’t walk from one place to the next. It helped to put the details in the book, stopped them floating off. There’d come a time when the board at school almost looked underwater. The numbers flew out of her head, and words too. She would see them congregating in the corners of the ceiling and beg them to return to her head. They smirked, and said, nope. She started to divert her attention to the birds on the roof of the mobile classroom outside, and the tree that grew in the middle of the playground. It rustled. It looked so friendly. She didn’t like going out to play at lunchtime. Since when had they got so complicated with all the rules? No, you don’t throw it to her! We told you! You are not doing it right again! She said to him late one night, as she was going to bed, Daddy, I fell and hurt my head. It was a couple of months ago, I think. Well, that’ll harden you not to do it again! he said.

On the Tuesday, the first place, a small flat, was spruced up within half an hour. The next one was more work because the people had stayed for a week; they had made it their home, with their toothbrushes still in the glass, the ring around the bath. There were clippings of nails on the floor. Roberta bagged up the dirty towels, put out the new ones. The third place was on the edge of the park. Ain’t nothing like a house party, Gary Jameson said, as they drove there. Party house, this place, last night anyway. Give me a ring when you’ve finished, Roberta. He gave her the key and she got the bags from the van.

Although someone had opened a few of the windows, the house smelt of smoke. In the kitchen there was a pile of broken glass, pushed over to one of the corners. At the side of the sofa there was an old condom, the colour of frogspawn. She went round with a bin bag, filling it with bottles and cans. It had been some party, for sure. The vacuum cleaner was in a cupboard under the stairs. It needed to be emptied and Roberta did this the way she had been shown. Always so much hair: a brown bird’s nest of the stuff. After the hoovering, she polished the surfaces, then went upstairs. There was piss all over the bathroom floor and the towels were a ton weight because they were sodding wet. In the first bedroom there was another condom. She stripped the bed, which was streaked brown with fake tan, put on the fresh stuff.

The day she hit her head they had gone to the derelict place, the old Kane garage, Roberta, her sister and Desmond Kane. They were up on the roof and next thing she woke up with the sky a burning blue and Desmond Kane’s face above her. He carried her home on his back and her sister put her in bed with a hot-water bottle. Don’t tell where we were or what happened. Her sister brought up a bowl of soup but she couldn’t drink it. It’s the flu, her sister said. You have the flu.

When she opened the door of the smaller bedroom, a little girl—about eight or nine—was sitting on the floor. She looked up at Roberta, who stared at her and then closed the door again. People had been found in the houses before. A pair had once been still asleep in one of the beds. Gary Jameson got them out pretty quickly. Roberta remembered their frightened faces. She looked to see if Gary Jameson was still outside, but he had gone. She stood on the landing before opening the door again.

I’ve been waiting, the girl said. Waiting for my mum.

Roberta didn’t reply.

Is my mum downstairs? she asked.

Roberta looked

Oh, the child said.

She had a basic face, as if someone in a hurry had drawn quick features on a pebble. Her brown hair was in a thin ponytail. She wore pyjama bottoms and a school sweatshirt with a logo of three children dancing in a circle above the words Newton P.S.

Did your mum bring you here? Roberta asked.

Yes. And I stayed in the room like she said.

You were meant to contact the police if you found a child. But Roberta didn’t think Mr Dalzell would appreciate her contacting the police. Plus, she had another job soon. Think! Think! Maybe she should contact Gary Jameson.

Am I leaving now? the girl asked.

The mother might have got stuck somewhere. Maybe the mother intended to come back. Maybe the mother had started feeling sick somewhere. She might have fallen in a K-hole. There was one time when the young guy who lived in the house was laid out in the kitchen after taking ketamine and Roberta thought he was dead. But a while later, he was back to normal. People might take the child away from the mother if they knew she had been left alone in a house like this.

Where do you live? Roberta asked.

We’ve only just moved to the new place. I don’t know the address.

But that’s your school, yeah? Roberta pointed to the sweatshirt.

The child looked down. That’s where I go, she said.

Well, said Roberta. I wonder what we should do. I am going to have to make a plan. Okay, she said. I have got the plan. You are going to stay here and then I will come back for you. You’ll know it’s me because I will knock like this. Four times. Loud soft loud soft. And you will let me in.

Okay, the child said.

Roberta was waiting outside when Gary Jameson came. She loaded the black bin bags into the van and gave him the key. On the way to the next place, he stopped at the garage to get petrol. He ambled across the forecourt like a cowboy going into the saloon and expecting a shoot-out. Roberta’s hands were shaking as she reached down to get the big key ring. Place with the yellow fob, place with the green door, big windows, the window-box one, where could they go, where could they go, not the park place and then, yes, do it, the gloomy old place that hadn’t been used in ages, yes, thread the key off the metal before he is back. Gary Jameson was there with a bar of chocolate for her.

Thank you, she said. Do you want a piece?

You’re okay, bird.

This next place, Roberta said. Just let me in and then go because I don’t need a lift back home again. It’s alright. I’ll leave the bags round the back for you.

Oh, is that right now? he said.

Yeah.

You must have a boy on the go.

I might well, she said.

After, she headed back to the house where the child was. She knew what she would do. She would take her to school the next day and by then the mother might be ready to pick her up. Or someone else. A granny or a sister. She would keep her safe until then. There was no need for the police.

Loud soft loud soft. She half-expected the child to have gone, but there she was.

Good girl, let’s go, Roberta said.

The child was wearing a coat. But she was still dressed in pyjama bottoms, now tucked into boots.

Do you wear that to school?

No, the child said. I wear a school skirt and socks. But I don’t have them with me.

Well, they would need to get those things. Roberta and the girl walked side by side when they left the house. Adult and child, Roberta said when they got on the bus, waiting for the bus-driver to query it, but he didn’t. Adult and child, she whispered to herself, as they made their way down the aisle to a seat at the back.

In the town, they found a shop that sold school uniforms on the second floor. Roberta held up a couple of pleated skirts to the child.

You’re skinny, she said. But I’m not. And now—she shoved the skirt down inside her coat—I’m even less skinny than I was before. You need socks too?

Yes, and the girl said she also needed a schoolbag. Roberta paid for that, a cheap one with a cat on the front. After walking around for a while, they sat down so that Roberta could copy in her little book the bus times and the route to the house and back again. The girl watched her, gave her a smile when she raised her head from the book. She told Roberta that the school started at nine o’clock.

When they got off the bus, there was a shop on the corner where they got cereal and milk. The girl said she didn’t need a lunch for the next day because she got dinner in school. The hall was dark when they entered the house, but Roberta didn’t know where the light was. When she eventually found it, they both looked down at the various letters on the mat, the numerous promotions leaflets and menus for takeaways.

Well, the postman left a lot of those this morning, Roberta said.

The living room had thick and dusty brocade curtains and a red velveteen three-piece suite. The carpet was big blowsy flowers ready to burst into bloom. The girl sat on the sofa with her legs tucked under her, staring up at the cobwebs where the walls met the ceiling.

Is it just you who lives here? she asked.

Yes. Just me. That’s the way I like it.

Because it was so cold, Roberta looked around to find an old blow heater. It smelt of burnt plastic and kept cutting out, but it generated some sporadic warmth.

Today I don’t really feel like cooking, Roberta said, so we’ll just have cereal for tea. Okay?

Okay, the child said.

They sat by the heater, the occasional sound of the spoons clinking off the bowls. All of a rush the child said that the reason her mum brought her was because one of the times she was left before, she tried to make herself something to eat and she started a fire because the kitchen roll got caught on the flame. People had to come to put it out and her mum was very, very angry when she came back.

Roberta considered this. Things catch fire, she said. It wasn’t your fault. Wasn’t your mistake. Eat up.

People make mistakes, big fat Xs all over the work and that teacher always watching, even if you scowled back. They put her at a desk by herself where people from the past had gouged their names in the wood. She put her name along with them. Then they lifted her out to sit in the little room with the plant and box of tissues to speak to the woman in the cardigan who made her say numbers backwards, find words in a swirl of colour. Mistakes again, so they sent her to that other school with its buses, where she had to sit with a plastic bag on her lap because she was sick every journey. When she looked out the window, people made faces, did things with their hands. She slowly mouthed Fuck you, which surprised them.

What time do you go to bed? Roberta asked.

Half eight, the child said. But can I read for a while?

You can.

Does my mum know I’m here?

Don’t you worry, Roberta said.

Later, Roberta prepared the room where the child would sleep. She shook the pillow, folded the corner of the duvet so it looked welcoming, wiped the chest of drawers and window sills with an apple disinfectant that she found under the sink.

The child was at the door. Will I go to bed now? she asked.

Yes, Roberta said. Take off that sweatshirt so it’s good for the morning.

The child did that. She put her head down and crossed her bony arms across her chest. Roberta went outside the room, took off her own jumper, then her T-shirt, then her vest. She put the T-shirt back on and then handed the vest to the girl.

Thank you, she said, the vest still warm in her hand.

When she climbed into bed, the child lay on her back, staring at the ceiling.

The reading! She needed to read. Roberta suddenly realised. She bounded back up the stairs with the brochures that had been put through the door. The girl sat up to read a promotional leaflet about PVC windows and fascia.

Thank you, she said. That’s great.

The dark pressed against the window and Roberta put on the heater again. Cognitive, cognitive, said the woman with the cardigan. Nothing to do with falling. But if she had had a mother she would have taken her to the hospital and then she would have gone to the school with the blue blazer just like her sister. When the people talked, they thought she couldn’t hear them, but she did. Disgusting the way she went off with her fancy man, they said. What’s a fancy man? she asked her sister.