Childhood sweetheart a b.., p.1

Childhood Sweetheart: A brilliantly dark and twisty psychological thriller, page 1

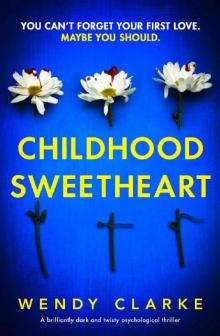

CHILDHOOD SWEETHEART

A BRILLIANTLY DARK AND TWISTY PSYCHOLOGICAL THRILLER

WENDY CLARKE

BOOKS BY WENDY CLARKE

Childhood Sweetheart

Blind Date

His Hidden Wife

The Bride

We Were Sisters

What She Saw

Available in audio

Blind Date (Available in the UK and the US)

His Hidden Wife (Available in the UK and the US)

The Bride (Available in the UK and the US)

We Were Sisters (Available in the UK and the US)

What She Saw (Available in the UK and the US)

CONTENTS

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Epilogue

What She Saw

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Hear More from Wendy

Books by Wendy Clarke

A Letter from Wendy

Blind Date

His Hidden Wife

The Bride

We Were Sisters

Acknowledgements

*

For everyone who loves my books

PROLOGUE

The most painful goodbyes are the ones that are never said and never explained.

The brothers stand silent, little more than a gull feather’s width between them, as their father points to the boat that’s been dragged onto the stones at the loch’s edge and unbuckles his belt.

From the edge of the forest, Seth sees the fear that crosses the face of one boy, the defiance etched in the hard stare of the other. He’s too far away to hear the lecture they’re getting but can guess the words. How the underwater currents could pull them away. How a sudden squall could whip the usually still water to a frenzy. How easy it would be on a freezing winter’s day such as this, for Loch Briona to take a life. Lowering his binoculars, he calls to his dog and steps back into the shadows.

The father’s hand tightens around the battered leather belt. From the window of the white house at the top of the hill above the lodges, Moira sees her husband, the man she loves despite everything, slowly draw it from the loops of his trousers. Sees her boy flinch and prays he won’t incite his father’s anger further.

As he folds his arms, squares up to the man as he’s always done, the little girl, Ailsa, squats on the concrete steps that lead to the wooden lodges. She sees the other boy, her best friend, pull at his brother’s shoulder. Knows he’ll be pleading with him not to do anything stupid. But, before she can find out what happens, her mother takes her hand. Tells her it’s not their business and leads her away.

Three sets of eyes.

A moment in time. Shaping all others.

Eleven years later, long after the cruel hand of death has visited, they will all have changed. The weak, the strong, the guilty, the innocent. Forever shackled to the past. Some alive. Some dead.

All regretting.

ONE

AILSA

Ailsa pulls the last of the sheets from the washing machine in the cold outhouse and presses her thumbs into the small of her back. Through the grimy, small-paned window she can just make out the Scandinavian-style lodges where birdwatchers and walkers stay from spring to autumn. The silver-freckled surface of Loch Briona bathed in late September sunshine at the bottom of the grassy slope.

Just out of sight is the lodge she shares with her son, Kyle. It’s larger than the others, set a little apart, its wooden steps leading to a raised deck affording a view of both the loch and the dark swathe of pine forest that surrounds the holiday complex on two sides. With its kitchen-living area, functional bathroom and two bedrooms, it’s all that she and Kyle need.

When Moira had asked why she hadn’t taken the bigger of the two bedrooms for herself rather than give it to Kyle, Ailsa had lied, saying she’d thought the view of the loch would be calming for her son. The real truth she’d kept hidden. There was no way to explain that she hadn’t wanted that room because of the boathouse. The wooden structure that jutted out onto the water on spindly legs just visible if you pressed your forehead to the glass.

Ailsa closes the washing machine door, trying to banish the image of the building’s weathered doors and rotten floorboards. The phantom smell of fish. She doesn’t mind having a smaller room if it stops her remembering what happened there when she was a child. Not much older than Kyle.

Too scared to tell anyone in case they didn’t believe her.

Too young to truly understand its significance.

Straightening up, Ailsa goes to the laundry room door where a glance at the sky shows dark clouds gathering. Banks of them. Solid as countries and casting shadows on the hills behind the main road that looks down on Loch Briona Lodges. Ailsa smiles at the term ‘main road’. Moira’s name for it, not hers, but it’s as main as they get on Bray, stretching from the harbour town of Trip, six miles to the east, all the way to Balmoor in the west. Another road joining it at the point where the forest turns into moorland. Connecting it to the main town of Elgin on the other side of Loch Briona and often impassable during a harsh winter.

Moira’s not back yet, the parking space next to the house still empty. She’s been Ailsa’s employer for the last eleven years and even now, when she’s in her uniform of battered wax jacket and wellingtons, it’s easy to forget the woman came from a wealthy family. Very easy. Not that Ailsa likes the word ‘employer’. Like the term ‘main road’, it strikes a false note, giving her relationship with the older woman a status that’s too formal. Yes, Moira might pay her wages, but, over the years, she’s been more of a mother to her than her own, and without her, she’d have no job, no home and certainly no stability for Kyle.

But, as she cleans the chalets and sweeps the wooden decks, the loch stretching out below her, serene or untamed as the weather sees fit, the thought is often there in her head. Intrusive but unspoken. How does Moira continue living here faced, every day, with the tragedy that blew her family apart? A devastation of such magnitude that it left in its wake a void that she and Kyle had struggled to fill.

Not that it had been easy for her either. Moira wasn’t the only one left to mourn.

The clouds have bunched and darkened, shutting down the sun. Ailsa shivers and steps back into the cold, stone room and rubs at her arms, the fabric of her cardigan wrinkling beneath her fingers. Yes, Moira might have lost her son, Callum, but because of that terrible night Ailsa had lost someone too. She’d lost Jonah.

She closes her eyes a moment, just his name enough for her heart to give its familiar lurch. She doesn’t often think of him, tries not to, and this is exactly why. It’s just too painful. The hurt still as raw as it was the day he left.

Ailsa turns away from the window, bending to lift the end of a white sheet that’s dragging on the tiles. But as she tucks it in with the rest, something feels wrong. Out of kilter. Just as it had earlier that morning.

Knowing she’s being silly, Ailsa drags the plastic basket along the tiled floor, and stuffs the bedding into the dryer. She can’t put her finger on what it is that’s worrying her. What caused her to push away the breakfast of bacon and scrambled eggs Moira had made her earlier that morning. Replacing her usual strong coffee with a cup of weak tea in the hope that it would calm her churning stomach. All she knows is that whatever this feeling is, it’s taken hold and grown. And it’s unnerving.

She shivers and pulls her cardigan around her. The feeling comes again – like milk curdling in her stomach. Usually, when she feels like this, it’s due to something Kyle’s done or said, but there have been no problems for a while. Her son’s hours of sleep are less erratic, and he usually only wakes once or twice now. Settling quickly when she goes into him. No, it’s something more than that; she’s just not sure what.

The metal door of the dryer is cold against Ailsa’s hip as she presses it closed. Thinking she hears a cry, she straightens and listens. She’s left the door to the outhouse open. The one to the kitchen of the old house too in case Kyle needs her.

Is it her

She’d left him engrossed in his Lego on the rug in front of the range in Moira’s kitchen, knowing from experience that it was better to let him stay than make him come with her if he didn’t want too. She’d be able to hear him through the open doors if he wanted anything and there was no danger of him wandering out on his own. The world is a frightening place for Kyle. A complicated jigsaw with the pieces moved into the wrong places. On his own, he’d be forever trying to rearrange them to make them fit better. Sometimes, Ailsa knows how that feels.

The cry comes again. Louder than before. There’s no mistaking it now. It is Kyle. Her son needs her.

Leaving the tumble drier rumbling, Ailsa kicks the washing basket aside and runs out into the small yard that houses the toilet and shower block and the wooden sauna. Moira’s house is one of the largest buildings on Bray, situated further up the hill where it can look down on the loch and the holiday lodges, and by the time Ailsa reaches the porched side door, she’s out of breath. She stops and listens, scared of what she’s going to find when she goes in. Trying to work out what might have happened.

The side door leads into a small lobby full of shoes. On the wall is a wooden shelf underneath which are several hooks – Kyle’s anorak the only coat hanging there. He’s quiet now, and not wanting to startle him, Ailsa steps over the walking boots and wellingtons on the floor to the kitchen door, positioning herself so that she can see him. He’s exactly where she left him half an hour ago, kneeling beside the Aga. But, instead of the intense concentration he’d had on his face earlier, he’s rocking. Forward and back. Forward and back. Forward and back.

A glance at the floor in front of him shows her what’s happened. Lego bricks are everywhere, the remains of the tower he’d been constructing. A tower, once completed, that would have been identical to the one he built yesterday and also the day before.

When the tower fell, the pieces had scattered into a kaleidoscope of colours and random patterns that Kyle must have found hard to cope with. Ailsa looks down at them, seeing them through her son’s eyes. Understanding what they represent to him: confusion, chaos, discord. The scattered pieces lying on the rug are in stark contrast to the orderly rows of individual colours Kyle had carefully placed before starting this latest project. Thirty pieces in each row – something Ailsa knows because he told her. Just like he told her the exact measurements of the tower on its completion.

Relieved that his outburst is nothing more than a bout of frustration at having failed in his task, Ailsa goes into the room. Putting her churning stomach down to something she ate, and knowing her son hates it when she’s ill, Ailsa composes her face.

‘All right, Kyle?’

Kyle looks up, his eyes meeting hers as she’s taught him, but he doesn’t return the smile she gives him. Instead, he frowns. ‘Did you know that a dog’s sense of smell is forty times better than ours? Did you know that they can sniff at the same time as breathing?’

Ailsa closes her eyes for a fraction of a second, then opens them again. ‘Yes, I know that, Kyle. You told me yesterday. And they don’t sweat.’

Kyle nods. ‘Yeah, Mum. Good remembering. Some are faster than a cheetah too.’

His obsession with dogs is a new thing. It used to be spiders and, before that, car number plates, though there aren’t that many to be seen on the small island of Bray. Most visitors preferring to leave their car on the mainland in order to travel on the more frequent foot passenger ferry. Those who have come to birdwatch, or visit the rutting grounds in autumn, are happy to make do with the local bus service or Douglas’s cab, when he isn’t serving behind the bar at The Stag down by the harbour in Trip. At Loch Briona Lodges, they go one better with Moira collecting the guests from the ferry in her new Land Rover.

She can hear Moira now, her wellingtons crunching on the gravel drive. She told her she was driving out to Ewan’s croft where she’d been promised a lamb for the freezer. Ailsa goes out to meet her, taking in the woman’s smart black trousers that balloon from her wellingtons and the red Fair Isle jumper, its pattern of vivid blue and yellow circling her neck. Covering both is the usual open wax jacket that had once belonged to Moira’s husband, Hugh, its green material worn at the elbows and in the creases. The quality of its waterproofing tested on a daily basis in winter.

The sight of it still makes Ailsa go cold. How can Moira want to wear it after the way he treated her? It’s like she’s clinging on to Hugh in some ghoulish way, unable to let go. Ailsa knows what the people in the village say when they see her in it, for gossip travels quickly on a small island. She should burn everything the bastard left behind. That’s what I’d do if my husband ran off and left me for one of his bits on the side.

Ailsa knows Moira hears the gossip too, but it’s not for the islanders to judge. She must have her reasons for wanting to keep him close, for despite him being a violent drunk, she’d clearly loved him. And they say love is blind.

The wind has picked up, playing with Ailsa’s hair, flapping it around her face. ‘You were gone a while. Get what you wanted?’

Moira glances over her shoulder at the Land Rover parked on the gravel drive. Something crosses her face but passes again before Ailsa can read it. ‘I suppose so. Managed to get away before Ewan started off on one of his rants about the birders camped at the croft. If he doesn’t like it, he shouldn’t have them stay.’ She gives Ailsa a tired smile. ‘Anyway, how’s your morning been?’

‘Fine.’ Ailsa points to the outhouse. ‘With so few guests this week, I’ve managed to get the last lot of sheets into the dryer. I’ll make up the new beds as soon as I’ve taken them out.’

Moira comes over to her and kisses her cheek. Her skin is cool, sweet-smelling, the press of her earring sharp against Ailsa’s jaw before she releases her.

‘Darling girl. What would I do without you?’

Another gust of wind blows between the buildings. Ailsa captures her hair in one hand, then, taking a band from around her wrist, secures it in its elastic embrace. As she does, she wonders, as she often does, how Moira always manages to look so well groomed. As though she’s stepped out of an office in the city rather than a four-wheel drive on a windswept isle off the north-west coast of Scotland.

As if reading her thoughts, Moira’s hand moves to her fair hair, which is pulled back tightly from her face into a neat bun. There are faint shadows under her eyes and the planes of her cheekbones seem sharper than usual. Her lips a little pinched.

‘Are you all right, Moira?’

Moira drops her hand to her side. ‘Yes, of course. I just didn’t sleep too well last night.’

‘It wasn’t Kyle, was it? He had a bad dream, but he quietened quickly.’ She thinks back to her son’s pale face, his forehead filmed with sweat. He’d been shouting. Something about a dog. She thinks of the questions he asked her a moment ago. The sooner he moves on to a new obsession, the better.

Moira gives her a reassuring smile. ‘No, of course not. You mustn’t ever think that.’ She points to the house. ‘Your lodge is nowhere near the house and, even if it was, the walls are so solid, a bomb could go off and I’d not hear it. Anyway, how is that wee man of yours? Built his tower yet?’