Lost treasure of the lan.., p.1

Lost Treasure of the Lanfang Republic, page 1

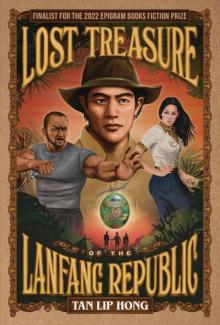

LOST TREASURE

OF THE

LANFANG REPUBLIC

Copyright © 2023 by Tan Lip Hong

Cover design by Nikki Rosales

Cover illustration by Yamaguchi Yohei

Published in Singapore by Epigram Books

www.epigram.sg

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher.

National Library Board, Singapore

Cataloguing in Publication Data

Name(s): Tan, Lip Hong.

Title: Lost treasure of the Lanfang Republic / Tan Lip Hong.

Description: First edition. | Singapore : Epigram Books, 2023.

Identifier: ISBN 978-981-49-8473-7 (paperback)

ISBN 978-981-49-8474-4 (ebook)

Subject(s): LCSH: Treasure hunting—Fiction. | Borneo—Fiction.

Classification: DDC S823—dc23

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

First edition, January 2023.

For my wife

Prologue

She came rushing in in her fussy old way, smelling of libraries and old books.

“Why are you still here?” she asked, squinting impatiently at Hector, her reading glasses swinging on a thin chain at her chest.

“Waiting for you,” Hector said testily.

“Waiting? What for? I’ll make my own way there when I’m done here. Get going now, or the committee’s going to be on my back again.”

She wasn’t as young as she used to be, and was prone to periods of haziness when she would dream of hill stations in India or the windy Malabar Coast, where she’d once spent her youth. She was wearing her summer sundress of flowery thin cloth, well suited to the recent hot days—it seemed that the days were always hot now. Her hair was pure white, tied up in a small bun at the back of her head, unruly strands escaping here and there, making her seem like some patient in her sickbed. There was nothing wrong with her; she just didn’t like to spend time with trifles.

“Okay, I’m going, I’m going.” Hector smiled. “See you later.”

He kissed his aunt on the left cheek, then skipped down the stairs and was gone through the door before she turned around to face the room again.

Putting on her reading glasses, she scanned the unruly room in front of her: books and magazines piled high on the old, heavy teak desk, more books and journals and files on old wooden shelves, bookcases that ran from floor to rafter, old papers strewn here and there on the worn sofa. She shook her head. Impossible to catalogue, all this stuff. Why even try?

When her husband Hean was still alive, they had tried, but failed. And when he had died, she had tried again and failed. There was just too much here, collected over decades, a lot of them antiques centuries old. The oldest bound volumes were of the first-known woodblock-printed sheets, containing Buddhist mantras—fragile when they were first produced, impossible to handle now. There were invaluable items here, but one had to sort through thousands of other old books, Qing-dynasty instruction manuals, ancient edicts, obscure original manuscripts, communist-era publications, forgotten journals, first-draft research papers, first-edition volumes, geographical and natural history periodicals, a ton of termite-eaten Life magazines, and newspaper clippings, before one might come to the important stuff.

She sighed. When she was gone, who would be able to do this? The lot would be dumped, for sure. Because to really, properly catalogue everything and do these books and documents justice, there would have to be enough history, geography and language experts at hand. A lot of them would be donated to the National Library, some kept, and the rest thrown out.

Finding what she was looking for in this mess would be like looking for the proverbial needle in the haystack, but she had no choice; there really wasn’t much time left. Where was it that she had last laid eyes on it, that thin, unbound sheaf of papers? Two-and-a-half dozen pages of notes handwritten in beautiful Chinese calligraphy, with an accompanying translation in English. It had been so long ago, when Hean was still alive. That had been one of his endless passions, and he had spent years tracking it down, then translating it and doing more research in libraries and universities across the region, talking to experts on the subject. He had spent so many years on this—his years in the wilderness, he liked to call them. He was still on the quest when he died. His life’s quest. And it was always the same: so near and yet so far.

Thinking about him made her eyes misty. She remembered the way he had been, the places they had been to, swimming off the pristine Malabar coast where the water was warm, walking the ancient streets of India, or standing on the shores of the Ganges watching thin old men with long white beards bathe themselves in the holy river.

She willed herself to stop thinking about him and concentrate on the task at hand. She had to find it. It was here somewhere. There was not much time now. With a tremor in her hands, she searched through the stacks of books and papers. Her hands tremored often now, even when she was not the least bit excited. Her knuckles were swollen and pained her much. She had stiffness in her fingers in the mornings, and sometimes, her left ring finger triggered badly.

But she had fire in her still, and a single-mindedness that age had not dulled. Through the piles she searched. On the high shelves, in the drawers and behind them, standing unsteadily on the wooden stepladder. The whole place was filled with dust, and many of the old manuscripts had to be handled carefully. When the sun dipped low on the horizon and the shadows grew long and the light too dim, she turned on the electric light and continued searching.

It had to be here somewhere. In the final weeks of his life, Hean had spent many hours in this room, turning things upside down, desperate to find whatever it was he was searching for. Whatever order there used to be in the place had been completely destroyed by his desperate sifting.

“I’m not far,” he kept saying. “Not far now. Almost there...”

And no one knew if he was really serious in those days, if he was really lucid or had fallen into some form of dementia. He scribbled endlessly in those days, sheaves of notes in his near illegible handwriting, made worse by his final weakness. He spoke as if he were still in the Sarawak Museum on the banks of the Sarawak River in leafy Kuching, or back in Bangladesh during the excavation of Vasu Vihara.

“My life’s work,” he mumbled. “For posterity...all this...almost there...”

She teared up again, thinking of all this, her fingers still sifting through the articles and books. She was bone thin, but seldom cold, although now, as a sudden breeze blew through the room from the open window, bringing with it a hint of coldness as if a storm was near, she shivered in spite of herself, the cloisonné-on-brass locket on her chest knocking against her breastbone. She could feel its weight now, its physical weight; she tried not to think of the weight of what was hidden in it. Best to let sleeping dogs lie.

Continuing to sift through the papers on the study desk, she came upon something mixed in with Hean’s other writings.

Wait. Was this it? What she had been searching for?

The sheaf of papers was folded in half, but it felt right. There was a familiarity to it. With trembling hands, she unfolded the pile and looked at the first page, yellowed with age. She scanned and quickly flipped through the other pages.

Yes, this was it. She clenched her fists and punched the air excitedly. She had finally found it! She took a deep breath. She couldn’t wait to tell Hector, to finally let him know about these papers. It was a legacy of sorts, now passed down to him.

But there was no time to think about that now. She needed to keep the papers safe. There had been danger before, and there would be danger again. Quickly, she looked around for a folder or a bag, something to put the papers in.

The wind came again, and she put her hands down on the papers to prevent them from flying around.

Someone had opened the door.

She looked up and saw a large, muscular man.

Suspicious immediately, she tried to think quickly. What should she do now?

“Yes?” she asked, trying to sound irritated and impatient. “What do you want?”

Her hands were still on the table, frantically pushing the papers under the other mess on the desk.

The man was eyeing her face intently, and her heart stopped when something made him look down, at her nervous hands on the desk.

He crossed the room right up to her, and stood in front of the heavy desk. He was wearing a light jacket and his hair was cropped short, fully exposing his thick neck and deeply tanned skin. She wasn’t sure if he was Chinese or Malay or some other Southeast Asian.

“Mrs Kee,” the man said. “I knew your husband.”

His voice was a deep growl, and he had an accent she couldn’t quite place. Not local. She squinted, trying to place him.

“You knew Kay Hean?” she asked, hoping that someone, Trixie, or Jane or one of the other assistants would come by.

“Yes,” the man said. “I knew him. I knew him well. A long time ago. He was a fool and a traitor. I would say this to his face, but he is no longer with us.”

His tone was ha

“You have something that I want,” he said, his voice low.

“Let go of me,” she said, but just as she tried to shake off his grip on her chin, his hand moved quickly to her chest, and in one swift motion, yanked at the locket resting on her chest. The thin chain snapped, and the man gathered everything up, locket and chain, in his large palm.

“You don’t know how long I’ve been waiting to have this in my hand,” he said, baring his teeth.

She put her hand up to the place on her throat where the chain had snapped, and tried to remember if she had seen him before.

He put down his large hand and his actions were brisk.

“Come,” he motioned for her to follow him as he backed slowly towards the door he had come through.

Her eyes flashed, but her arms were extended stiffly by her sides.

“I don’t know what you are up to,” she said, “but you better leave now.”

“I said come,” he said darkly.

Reluctantly, she went around the desk towards him, hiding the papers from his view with her body. She could sense that he was dangerous, but maybe he had got what he wanted with the locket and would now leave.

Please leave, she prayed.

He pointed to the middle of the room where a messy pile of papers still lay on the ground: “Here.”

She moved hesitantly, stealing a glance at the door behind the man and hoping against hope that someone would come through it and stop all this.

“Now,” he said, and he always liked the next part, which he said clearly to her:

“Get down on your knees—”

She looked at him angrily. “What in the world are you talking about?”

“I said”—he went behind her, moving fast for a big man, and kicked her roughly in the back of both of her frail knees—“get down on your knees...”—and she fell unsteadily onto her knees.

“And pray...”

She felt something cold against her left temple.

Steadying herself carefully, she started to pray, and thought again of Hean, and wistfully, of India.

You look beautiful, Sook Lian, Hean was saying in the waning light along the golden coast. I love you—

And when the shot came, she didn’t even hear it.

1

Banyan Tree Resort, Bintan Island, Bintan Regency, Indonesia

Hector awoke with a start. For a long moment, he didn’t know where he was. His body ached all over, but the sheets were smooth and clean, the bed big and properly firm. The room was dark, quiet: only the soft hiss of the air conditioner could be heard.

It was strangely pleasant, this moment of amnesia, but at the back of his mind he knew that everything would soon come flooding back and he would become overwhelmed.

He turned over in the bed and dozed for a while longer, and when he awoke again, the light in the room was different, brighter. A faint mustiness hung in the air, like mould on old wood or damp folded clothes. It reminded him of the sea and old boats with dirty bilges.

He lay with his arms spread out on the spacious hardwood four-poster bed, facing the ceiling, and the events of the past few weeks slowly came back to him. He remembered the wake, the throngs of relatives and people he’d never met offering their condolences, the white tent, the wreaths of flowers, the endless rites, his own deep grief and overwhelming exhaustion. He remembered the leathery-skinned monks in saffron robes and the unkempt youths of the funeral band. He remembered the sound of the chanting, the music of the marching band, the endless drone of conversation among relatives and friends meeting for the first time in many years. He remembered the smell of the joss sticks mixed with that of the flowers from the wreaths.

It had been a closed casket, because what remained of his aunt after the fire hadn’t been pleasant. The old house, the grand old house, along with everything in it, had been burnt to the ground.

And his aunt, frail yet feisty, headstrong and independent, was gone forever. She had been this way to him for as long as he could remember, it seemed: hair pure white, and delicate but full of strength. In this sense, she had been there for him for as long a time, ever since his parents had died. He had been her only living relative after his uncle’s death, and she had been his. There were days when he imagined that she would outlive him even, but now, suddenly, urgently and without reason, she was gone.

And it did seem urgent—the final few weeks. There seemed to be so much going on, his aunt unusually restless. The National Library Board had been interested in a large part of his uncle’s collection, and his aunt was keen to donate the most valuable books and documents to them. She hired three assistants to help out at her own expense. They were undergraduate and graduate students, and they came in the afternoons and on weekends, cataloguing books and papers, organising the mess into neat piles. There was much to be done, and the work was painstakingly slow. They worked in white cotton gloves to separate the oldest papers and books with plain white acid-free paper, matted and framed the most fragile of volumes under conservation glass. Over the weeks, it became clear that there was a lot that was valuable here, and the chief librarian who came over to help with the cataloguing and databasing never failed to admonish Hector’s aunt to increase security around the house.

“These are priceless!” the chief librarian would say as she walked around his uncle’s library. White-gloved herself, she would carefully examine the volumes, sighing at the sight of their disintegration under attack by mould and silverfish and booklice. The bound volumes from after the 1840s were brittle and yellow due to the lignin and acids present in the paper.

“Mrs Kee, please, please, keep these volumes safe. Remember to lock up the library at night! If anyone knew about this collection...”

But his aunt had brushed off her concern. She had been living with these books in this house for decades, and nobody had tried to steal anything.

In days long past, when she had been younger, her husband used to entertain earnest researchers and graduate and post-graduate students in his library. Those were the days when his private collection of books on South and Southeast Asia was known to be the most extensive in the country, and his knowledge and scholarship on the subject even more so, garnering him great respect. He had published many papers of repute, and he had travelled widely, sourcing for old books and papers in antiquarian bookstores, libraries and private collections. His published works on overseas Chinese in South and Southeast Asia were exemplary. His esteem, coupled with his approachable nature, his keenness to teach and share his knowledge, even if a discourse ran late into the night, ensured a steady stream of visitors to the old house and library.

Of course, in those days, the library was much neater, even if he never had a very coherent system of cataloguing his volumes. He just knew where everything was. A Hundred Years of Chinese in South East Asia? Third shelf, second row, first cupboard on the right. Admiral Cheng Ho and the Spread of Islam in the Malay Archipelago? Two shelves below that. Suvarnabhumi & Suvarnadvipa: The Golden Land & Peninsula? Three shelves up and two rows to the right. These and ten thousand other volumes he had filed neatly and logically in his head.

Yet, even then, there was already the one thing that gnawed at his reputation among his closest peers, even if it was not widely known, and that was his conviction of the validity of his long and lonely quest: the hours he spent chasing cold clues, poring over old papers, visiting old smoke-blackened temples and ancient shrines, photographing and pencil-tracing bas-relief calligraphy. It was his obsession, this quest, and no one really understood it. From the beginning, he spent many evenings trying to convince his closest friends of the existence of the site and the trail to it, and they had long arguments into the night.

“You’re talking about some Holy Grail or Yamashita’s gold—it doesn’t exist,” they would say and shake their heads.

He ignored them and persisted. And over the years, as his own conviction grew stronger, his friends’ in him grew weaker. Their eyes would glaze over whenever he began another long tirade, until, in the end, he withdrew, and never spoke of his quest to any of them again, not to anyone except Sook Lian, but even she was only half-listening to him most of the time.