The everlasting now, p.1

The Everlasting Now, page 1

Published by

PEACHTREE PUBLISHING COMPANY

1700 Chattahoochee Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112

www.peachtree-online.com

Text © 2010 by Sara Harrell Banks

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

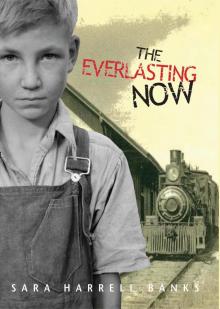

Cover design by Loraine M. Joyner

Book design and composition by Melanie McMahon Ives

ebook ISBN: 978-1-68263-303-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Banks, Sara H., 1942–

The Everlasting Now / written by Sara Harrell Banks.

p. cm.

Summary: In 1937 Alabama, eleven-year-old Brother helps with his mother’s boardinghouse, gains insight into prejudice when he befriends the nephew of the family’s maid, and dreams of riding a train one day with the railroad men who serve as his substitute fathers.

ISBN 978-1-56145-525-6 / 1-56145-525-3

[1. Boardinghouses—Fiction. 2. Depressions—1929—Fiction. 3. Friendship—Fiction. 4. Race relations—Fiction. 5. Family life—Alabama—Fiction. 6. Alabama—History—20th century—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.B22635Ch 2010

[Fic]—dc22

2009024512

For my brother Mike Harrell

and in loving memory of our stepfather

Edward L. Cooper,

engineer, Central of Georgia Railroad

—S. H. B.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

About the Author

Chapter One

When I first met Champion Luckey, I didn’t know that he was going to change my life. Maybe you never know when that’s going to happen; it’s not like something you’re expecting. It’s more like getting struck by lightning and living to tell about it.

’Course he was the one who got struck first and I did it, but I didn’t mean to.

The reason I met him in the first place was because of his aunt, Lily Luther. She’s the cook at our boardinghouse, and pretty much runs everything, including me.

One day, I asked Mama if we paid Lily.

“Of course,” she said.

“Not enough,” said Lily from the kitchen.

“Well, if she works for us,” I whispered, “how come she’s the boss of everything?”

“Because she’s better at it than I am,” said Mama.

* * *

On the first day of summer vacation, I slept late, then went downstairs for breakfast. Lily was standing at the Roper stove stirring a pot of black-eyed peas and listening to Sugar Blues on the radio, her skinny body swaying in time to the music.

“’Bout time you showed up, Brother,” she said. “I need you to go to the dairy for buttermilk. The railroad men’ll be here directly, and they’ll be expectin’ my biscuits.”

I picked up a piece of toast and started buttering it. “Can’t I eat breakfast first?”

Lily watched me with her hawk eyes. Her skin’s the color of sourwood honey—not brown and not black. She wore a white flower behind one ear. “That’s enough butter,” she said.

“This toast is cold, it needs more.”

“Brother Sayre, put the buttered sides against your tongue. It’ll taste fine. If you’d come to breakfast when you’re supposed to, instead of polin’ around wastin’ time, it wouldn’t be cold. Hurry up, now. Get two jars of jelly from the pantry—scuppernong, the kind Mr. Holman likes.”

That meant that I was to go swap something for something else. This time we were gonna swap jelly for buttermilk at Mr. Holman’s dairy. Swapping stuff was a big thing in Snow Hill, Alabama, in 1937. We were in the Great Depression, although there was nothing great about it. Songs were written about it and how everybody was suffering. Mama’s always singing about hard times, railroads, and lonesome valleys. Lily just sings the blues.

* * *

Seems like hard times happened to everybody. The stock market crashed, so a lot of people lost all their money; then there was a run on the banks and folks that had money took it out of the banks. A terrible dust storm in Oklahoma and Kansas ruined the crops in the fields, so farmers had to leave their farms and go to California to find work. Some did, some didn’t.

Here in Snow Hill, the Mercantile Bank closed, the shirt factory shut down, men got laid off at the sawmill, and some stores had to close ’cause there wasn’t any business. About the only real business that was still working was the railroad.

My daddy was the editor and publisher of the town’s only newspaper, the Choctaw Herald. And it had to shut down. He explained that since folks couldn’t afford to advertise in the paper, he couldn’t afford to print it. He also said that a town without a newspaper was a poor town, indeed. After he closed the newspaper office, he left home to look for work. And that’s when the worst thing of all happened to our family.

Daddy went to North Carolina to apply for a job at a big paper. But when he got there, the people who worked for the paper—the journalists, reporters, and linotype operators—went on strike against the paper. Well, being a newspaper man, Daddy couldn’t cross the picket lines. Then, delivery trucks rolled up and instead of picking up papers, men got out of the trucks and started beating the strikers. That’s when Daddy got killed. He was just trying to help, but I guess they got him mixed up with the strikers and somebody hit him in the head with a tire iron. That was two years ago. We all miss him something awful.

My mama, my sister Swan, and I live in Grandpapa Yeatman’s big old house that he’d left to Mama when he died. Because of the Depression, we didn’t have much money, and there weren’t many jobs in Snow Hill.

“But we have to make a living,” said Mama. “Only I can’t get a job around here. It’s hard enough for men to find jobs. Besides, I don’t know how to do anything but keep house.”

“You can do lots of things,” I said. “You’re a good reader and a pretty good cook, and you grow stuff too.”

“Nothing I could get paid for,” she said, “but thank you anyway. We’ll think of something.”

She started walking through the house like she was looking for something. I followed her upstairs. She went into each of the five bedrooms and even into the trunk room that belongs to my little sister. Then we went through all the rooms downstairs. And when she finished the tour, Mama stood there looking up at the picture of Grandpapa Yeatman in his black judge’s robe hanging over the mantle. “Your grandpapa left me this house to do with as I please,” she told me. “And he’d have wanted us to survive these hard times. In fact, he’d have expected us to survive.”

So she decided to open a boardinghouse for nice people.

Some people in town didn’t think she should, since she was the judge’s daughter and it didn’t look proper. They acted like it was their house, instead of ours. But Mama paid them no mind, she just went about her business. And that’s when Lily came to work for us and started to run our lives.

* * *

Lily took the pot of peas off the stove and, putting her hands on her hips, gave me her hawk look.

“Brother Sayre,” she said, “stop daydreamin’ and get about your business.”

A railroad calendar hung on the inside of the pantry door. On it was a picture of The Twentieth Century Limited, the most beautiful steam engine in the world, rounding a curve of track like she’s riding to glory. Mr. Edwards, who’s one of our boarders and a railroad engineer, had given it to me.

Homemade jellies, preserves, fruits, and vegetables lined the shelves from top to bottom. We grew most of what we ate. Every season, Mama and Lily put up peaches, tomatoes, applesauce, beans, watermelon pickles, and just about anything else that grew in the garden. I took down two jars of golden scuppernong jelly and patted the calendar on my way out.

“Lily,” I said, putting the jelly jars into a paper sack, “reckon how long this Depression’s gonna last?”

“Don’t be asking me about the Depression,” she said. “It don’t mean much to me. Don’t mean much to any Negroes. We was born in depression. It only became official when it hit the whites. Now, before you go, run on and see does your mama want anything from town.”

I went upstairs to the sewing room. I heard Mama before I saw her. She was singing about trains, keeping time with her foot on the treadle of the sewing machine. “This train is bound for glory, this train…” Thump…thump…thump…

Mama was mending sheets. She’d split them down the middle where they were worn, turn the outside edges to the inside, then make a new seam. Keepi

She looked up when I came in. She was wearing one of Daddy’s old shirts and trousers rolled at the ankles. Her curly brown hair was piled on top of her head.

“Lily says do you need anything from town?”

“Just the mail,” she said. “And I’d like for you to stop by the library. Miss Eulalie has a book for me.”

Downstairs, in the shadowy hall, a man’s hat hung on the hall tree. It’s my daddy’s best hat, a dark brown Dunlop felt with a kind of silky hatband. After his funeral, the preacher said I’d have to be the man of the house. That was a joke. I was only ten when Daddy died. But that’s when I claimed the hat for my own. It was too big, but I started wearing it anyway, hoping it’d make me look older.

I’m almost twelve now, and I still don’t look like the man of any house. I’m skinny, there’s a gap between my front teeth, and my hair flops down over my forehead like I’m wearing bangs. I looked in the mirror, tilted the hat the way Daddy had worn it, and went out the front door.

My sister Swan, who’s eight, was sitting in the wooden swing with her cat, Shirley Boligee, a calico with white fur and splotches the color of orange marmalade.

Twisting a strand of her blonde curly hair, Swan looked up from reading Mary Poppins. The bridge of her nose was peppered with freckles.

“Where you goin’?”

“To town, then the dairy,” I said.

“Can I go?”

“No. It’s too far and you’d whine all the way home.”

“Then bring me back a Goo Goo Cluster,” she said, batting her eyelashes like she always does when she wants something.

“I don’t have a nickel for candy,” I said. “I don’t even have a nickel.”

* * *

Our house is on Old Post Road, about where town ends and country begins. There’s a white wooden fence around the property. A gravel drive leading up to the side of the house has a cattle gap at the end that makes a rolling sound like thunder when somebody drives over it. I walked down to the front gate and saw that somebody had drawn another picture of a cat on one of the fence posts. It’s a hobo sign that means “a kindhearted woman lives here.”

There’s lots of folks wandering around because they don’t have any homes on account of the Depression. Hobos find us because of the marks on the fence posts. Mama said they’re secret maps showing where they can find a meal or work. Sometimes Lily threatens to scrub off the signs.

“Those folks are gon’ eat us out of house and home,” she said. But the marks stay and the hungry get fed.

Chapter Two

The marble floor of the post office was cool under my bare feet. Mr. Bartram, the postmaster, stood at the brass-grilled window, his green eyeshade reflecting the slow-turning ceiling fan. He was looking over at the mural painted on the opposite wall. Field hands were working the cotton fields, picking the bolls and putting them in bags slung over their shoulders. They were all smiling to beat the band. But there’s nothing to smile about. Picking cotton is just hard work. A lot of it goes on around here.

“That Federal Arts Project, the FAP, that the gov’ment runs is a good thing, I reckon,” he said. “It puts artists to work and all, but the fella painted that one sure didn’t know ’bout cotton.”

As he handed me the mail, Miz Edna Earl crossed the lobby, the heels of her shoes clicking like castanets on the marble floor…tippy tap…tippy tap…tippy tap. She was short and plump, and when she walked, she tilted from side to side, like her girdle was too tight.

“Mornin’, Mr. Bartram,” she said. She gave me a hard look. “You’re supposed to take your hat off in the presence of a lady, Brother.”

I took it off ’cause I didn’t want to have to explain my daddy’s hat to her, again.

Miz Edna Earl rented out rooms, too, but was too stingy to give her boarders a decent meal. Nobody stayed with her unless they were lost or flat-out desperate. She couldn’t stand it that our boarders worked for the Southern Railroad and could pay board. And not only that, everybody in town respected railroad men. And the engineer, Mr. Edwards, was treated like a real important person, which he is.

“Are y’all having problems with hobos out your way, Brother?” Miz Edna Earl asked. “They surely are a problem in town. There’s no excuse for begging, in my opinion.” She acted like she’d never heard of the Depression.

“They come by from time to time,” I said, backing toward the door. For sure, nobody’d ever draw a cat figure on her fence posts.

When I got outside, I put my hat back on and took a deep breath; the air smelled of dust, honeysuckle, and oak leaves. I walked around the corner to the library, a small white house only two rooms deep. The uneven, splintery floors creaked under my feet as I went inside. Nobody was there except the librarian. I took off my hat and went over to the desk. A vase of pink and white roses smelled sweet in the warm room.

Miss Eulalie peered at me over her glasses. “Good to see you, Brother,” she said, picking up a book and removing the note tucked in it.

“I have The Good Earth, by Pearl S. Buck, for your mama.” She always said the author’s name along with the title. While she checked it out, I went over to the shelves and picked out Wild Horse Mesa. Mr. Edwards had got me started on Zane Grey’s books. I liked them a lot. I told Miss Eulalie goodbye and put my hat back on. Just as I stepped onto the porch, the sheriff came out of the jailhouse across the street.

Sheriff Montrose “Piggy” Hamm was in full uniform, with hobnail boots, a pistol, bullets on a belt around his fat belly, and a mean-looking blackjack in his back pocket.

I was afraid of him. He hadn’t ever done anything to me, but he looked like he wanted to. Once I found a dead bird in the woods; maggots were crawling over it. It made me sick and I threw up in the bushes. I didn’t tell ’cause I didn’t want anybody to think I’m a sissy. But that’s how the sheriff made me feel.

He watched me from across the street. As I reached the bottom step, he quick slapped his hands against his sides and stared straight at me. Slowly, he raised his right hand like it was a pistol. With his other hand, he pulled his thumb back like he was cocking it. Then, aiming the make-believe gun at me, he pulled the trigger.

“Bang!” he said, grinning like a mule eating briars.

He thinks he’s funny, but he’s not. He’s just a big bully. Mama said she couldn’t understand how he got the job in the first place. He’d come to Snow Hill from some other town after he’d been fired. But the mayor hired him anyway.

I walked away like I didn’t even see him, paying him no mind. But I was sure glad when I turned the corner and was out of his sight. I hightailed it out of there, fast as I could.

On the dusty road to the dairy, my feet were soon covered in red clay dust. My overalls were sticking to my back, and I was sweating under Daddy’s hat. Clouds of midges rose up from the grass like tiny, buggy tornadoes, and the sack of jelly jars, mail, and books felt heavier and heavier.

Down the road, a bicycle rider wobbled in and out of patches of shade. A long stick stuck straight out from one side of his bike. A minute later, he wheeled up to me in a cloud of dust.

Lucius Polite was a tall, skinny man with only one leg; the other got cut off on the railroad tracks a long time ago. He balanced his bicycle by using his crutch on the same side as his one leg.

“Whuh’s Mr. Saywa?” said Lucius, puffing the words out like he was blowing out a candle. He couldn’t pronounce the letter r.

“He’s gone, Lucius,” I said. I’d told him a hundred times my daddy was dead, but he always asked about him.

“I’m sowwy,” he said.

Years ago, Daddy bought Lucius a bicycle and taught him to ride it. Lucius never forgot him. I guess he hadn’t known many kindnesses in his life.

He rubbed at his hair, which was full of leaves and twigs. “I need me a hat,” he said. He seemed to be admiring mine, but since his left eye wandered, it was hard to tell. Some folks said Lucius had second sight on account of his funny eye; they thought he could see into the future. He’d never predicted anything except rain, as far as I know.

“Maybe I can find one for you at home,” I said, “but I’m not making a promise.”

Lucius smiled, then rode off to parts unknown. He didn’t have a home; sometimes he slept in a boxcar on a railroad siding, other times he stayed in a shed somewhere in the woods. That could account for the state of his hair. A hat might help, I thought.