At my mothers knee and.., p.1

At My Mother's Knee...And Other Low Joints, page 1

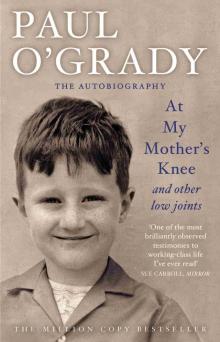

ABOUT THE BOOK

* * *

In this first volume of his multi-million-selling autobiography, Paul O’Grady tells the story of his early life in Birkenhead that started him on the long and winding road from mischievous altar boy to national treasure. It is a brilliantly evoked, hilarious and often moving tale of gossip in the back yard, bragging in the corner shop and slanging matches on the front doorstep, populated by larger-than-life characters with hearts of gold and tongues as sharp as razors.

At My Mother’s Knee features an unforgettable cast of rogues, rascals, lovers, fighters, saints and sinners – and one iconic bus conductress. It’s a book which really does have something for everyone and which reminds us that, when all’s said and done, there’s a bit of savage in all of us …

CONTENTS

* * *

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Picture Section

Index

About the Author

Also by Paul O’Grady

Copyright

Praise for At My Mother’s Knee:

‘Funny, well observed and recognisably human. Soon you start to wonder why all celebrity autobiographies can’t be like this’ Private Eye

‘Paul speaks with warmth and hilarity about a childhood filled with poverty, and reveals a cast of characters with whom he could have created an entire comedy series. Hugely interesting and entertaining’ Heat

‘Among the three-for-two slew of sleb lit heaped on the tables of the nation’s major bookshops … At My Mother’s Knee distinguishes itself on every level’ Carol Ann Duffy, Observer

‘While most celeb memoirs are as memorable as an air kiss, O’Grady’s is a proper snog’ The Scotsman

‘Warmly funny, dry and mischievous … Genuine and brilliant’ Daily Mail

www.penguin.co.uk

In memory of the Savage Sisters – Mary, Anne and Christine – without whom my world would’ve been a much duller place to grow up in.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

* * *

I’d like to thank Doug Young at Transworld for his patience, my sister Sheila for coping with the endless questions and phone calls at all hours of the day and night when I needed information about the clan, and everybody who put up with my moaning as I sat writing this bloody thing when all I really wanted to do was to go out and play.

FOREWORD

* * *

It feels like decades ago that I sat down to write this book. At the time I was presenting a nightly chat show and each evening when I got home from the studio I’d grab something quick to eat, go through the scripts for the next night’s show and then get stuck into this saga of my early life until the early hours of the morning. Originally, my intention was to cover everything about my life up to present day but after checking the word count on my laptop one night, I was more than a bit concerned to find that I was way over the target number of words required and I was still only seventeen years old.

Thankfully my publishers claimed they didn’t mind and said I could always write another book to cover the remaining years. I took them at their word and, so far, I’ve written another four, something I never thought I’d achieve in a million years.

I wrote this book in a wide variety of places: in bed, on the train up to London, sat at the kitchen table with Janice Long on the radio to keep me company. I wrote some of it in a hotel room in Hanoi, another few chapters at Raffles Hotel in Singapore – in fact any chance I got I’d open up the laptop and tap away with two fingers.

Writing had quickly become both an enjoyable obsession and a monkey on my back. If I allowed myself a night out or a few hours slumped on the sofa watching the telly there was always the nagging voice of guilt telling me that I should really be finishing ‘The Book’ and not lazing around.

When I did finally finish the book, the sense of relief and of a task completed was overwhelming. It was also tinged with regret, as if I’d said goodbye to someone I’d told all my secrets to and now our all-consuming relationship was over.

What the hell was I going to do with myself now? This bloody book had taken over my life and now it had walked out on me. I was at a total loss so I did the only thing possible – I sat down and started on another one.

I’m still writing but mostly for my own amusement. I’ve written a children’s book (which typically is far too long and seriously needs editing) but I’ve gone off the boil with it now and so I doubt it will ever see the light of day. I started on another, this time determined not to go over the 25-30,000 words which is the norm for a kids’ book but at the time of writing I’ve shelved it as I’m not in the mood at the moment.

There’s a load of short stories knocking about somewhere and even a spoof novelette a la Barbara Cartland called Lift My Veil and Kiss Me penned by that famous author of torrid romantic fiction, Miss Lilian Blythwood. But, as I said, these are for my own amusement.

Revisiting At My Mother’s Knee … and other Low Joints today I have rewritten some parts for this edition as I couldn’t resist it. I’ve softened a few characters as I may have got carried away the first time around and I’ve corrected some details that I’d got wrong but that’s all I’ve allowed myself to do.

The Birkenhead of this book no longer exists. Although the old homestead still stands, the majority of people mentioned are sadly no longer with us. The last time I was in Birkenhead was for the funeral of my cousin John and, on the way back, I asked the driver of the car to stop at Holly Grove so I could have a look at the house I grew up in.

The last time I had stood at the bottom of the Grove was over thirty years ago. My mother had died and after clearing out our rented house I was reluctantly on my way back to London, broken-hearted at having to leave. I seem to remember that I was carrying, amongst other bits and pieces, a battered old chip pan which ended up rolling down the hill and on to the Old Chester Road.

Surprisingly, I felt no rush of nostalgia, just the usual rush of wind blasting up the hill from the River Mersey as it always did on a blustery day.

The disturbing thought did cross my mind that if things hadn’t turned out differently for me would I still be living there? Living on my own and sat on the sofa right at this very minute watching Countdown? I banished these thoughts quickly and regretted coming on this pilgrimage as, in some way, it had unsettled me. I’d expected more: exactly what, I didn’t know but one thing was for sure, and that was that the curtain had finally come down on the first few acts of my life and the cast had left the stage for good.

Our house (I still thought of it as ‘our house’) now had new windows and the frosted glass in my sister’s bedroom window indicated that the new owners had sensibly turned it into a bathroom. My mother’s pride and joy, her garden, looked like it had been concreted over to make way for a car and there was a new front door. The high-rise flats that had dominated Sidney Road had been demolished and in their place were smart, well-kept houses allowing the residents of Holly Grove the most magnificent views across the Mersey.

It was time to go home, to the new home that had claimed me as there was nothing left for me here apart from memories that, try as I might, I was having trouble recalling. It was apparent that the part of the brain that recorded and stored nostalgic memories was stubbornly refusing to show the film reel today.

I tried to visualize Mrs Long sweeping down her steps and my Ma standing in the garden talking to Dot next door over the fence but I couldn’t. My inability to conjure up mental images possibly had something to do with just having left the grave of one of my favourite cousins. Sorrow numbs the mind and my subconscious was protecting me from taking on another memorial just yet.

Not wanting to hang around any longer I silently said my goodbyes and got into the car. I wasn’t staggering down the hill laden with carrier bags and carrying a chip pan this time, I was leaving by car. Even so, I couldn’t resist the temptation to turn around and take one last look as we drove off and amidst all the changes to the neighbourhood that we were driving past I hoped that Holly Grove would be left well alone by the developers and remain standing for many more years to come.

I’ve happy memories of that Grove, filled as it was with interesting characters who were as close to me as family. I wonder what they’d all have to say about the modern world today? Plenty, I should imagine, and there’d be some wonderful invective that’s for sure.

Tranmere and Birkenhead was my world at one time and it still holds a special place in my heart today even though it has changed and much of what I remember has long gone. That’s why I was glad to revisit it when I wrote this book before – to quote my friend Alan Amsby, ‘I forget to remember.’

I hope you enjoy this book.

Paul O’Grady

October 2018

CHAPTER ONE

AT HOME I’VE got a box containing what I suppose you might call the Family Archives. Family Archives sounds very grand but it’s actually just an ordinary cardboard box containing an assortment of birth certificates, letters, old diaries and sepia photographs – the flotsam and jetsam of lives past. There’s even a pair of yellowing false teeth wrapped up in a handkerchief. God knows who they belonged to. It could have been any one of my long-dead forebears.

When I was growing up in Birkenhead, nearly every adult I knew had false teeth or at least had a couple of fake choppers on a dental plate – either that or no teeth at all. My mother, christened Mary but known to everyone as Molly, had every tooth in her head extracted when false teeth became available on the National Health. She came from a generation where a poor diet and only the most primitive dental hygiene had taken its toll on working-class teeth, therefore a set of gleaming white gnashers courtesy of the NHS was a highly desirable acquisition.

In the early sixties, when she was only forty-four, she underwent this extreme dentistry. I remember her then as being quite slim and pretty, though I can’t recall what condition her teeth were in. She used to say that the reason she’d had them all taken out was because she had a mouthful of teeth ‘like a row of bombed houses’, which was a slight exaggeration. Like everyone else, she had all her teeth out because it was fashionable.

The sight of her lying in bed, moaning softly, a tea towel pressed to her swollen mouth and a bucket for blood on the floor beside her, horrified me. That nightmare scene put me off going to the dentist for life. Nothing and nobody could persuade me to go, and I’m still the same today. OK, I might not develop rigor mortis, throw myself on the front-room floor and hold my breath until my face turns a vivid scarlet at the mere suggestion of a check-up any more, but if a tooth is playing up I’ll stupidly ignore it until the final hour. When I’m defeated by the pain and my cheek is as swollen as Popeye’s I’ll give in and go for treatment.

My patient dad would try and gently coax me into taking the trip to see Mr Aboud, our dentist, inevitably with no luck. Eventually my mother, exasperated by my carry-on, would get me there by means of devious trickery. On the pretext of visiting a clothes shop called Carson’s that just happened to be close to Aboud’s House of Torture, she’d whip me into his surgery with the speed and efficiency of the Childcatcher before I realized what was happening.

Mr Aboud, a dapper little man who wore neroli oil in his hair and spoke with an exotic accent – if he had chosen acting instead of dentistry he would have made the perfect Hercule Poirot – would place me firmly in his chair and press the foul-smelling rubber mask over my nose and mouth, telling me to ‘Close your eyes, child, and breathe deeeeply, deeply …’ To my ears he sounded just like Bela Lugosi in the Dracula films I’d seen on the telly. The gas would take effect and, slipping into a coma for what felt like hours but was actually only seconds, I would have wild, technicolour dreams and come to with a start on the leather bench in the waiting room, retching from the after-effects of the gas into a bloodied bowl held by my mother.

Dentistry has come a long way since the sixties. I’ve been through more dentists than I have socks over the years, but now I’ve finally found a sympathetic marvel I’m a lot better. I still won’t have an anaesthetic though; I don’t like the after-effects. The dentist’s creed back then was ‘rip them out’. My aunty Chris, who kept all her extracted teeth wrapped in tissue in a jewellery box in her bedroom and was always threatening to have the poisonous-looking fangs made into a necklace, could never understand ‘why anyone would want to spend their lives rootin’ around people’s gobs’ and dismissed all dentists as butchers.

After she’d had weeks of soup and soggy toast, the long-awaited day came when Mr Aboud proudly presented my mother with her brand new set of dentures. She went straight from the dentist’s to her sisters, Annie and Chrissie, and the new teeth were premiered in their back kitchen.

‘Come on then, Moll, give us a gander at the new choppers,’ said Annie, rubbing her hands together like a bookie with a hot tip. My mum, lips pursed tightly, removed her headscarf and arranged herself by the kitchen sink so that the light from the window would catch the full effect of the revelation. She ran her tongue back and forth across the teeth, cleared her throat and then slowly curled back her top and bottom lips, rather like a camel, to expose a set of startling white tombstones. For a moment, nobody spoke. You could have heard a pin drop.

‘Jesus tonight,’ said Aunty Chris, ‘it’s Mr Ed.’

My mum hated those teeth. They joined the ranks of her bêtes noires. The reasons she loathed the teeth were many. They were agony. They crucified her, it was like having a mouthful of barbed wire wrapped around your gums. She couldn’t eat with them, they fell out when she talked and she wasn’t bloody wearing them for no amount of sodding money so you can shove that in your pipe, sunbeam, and smoke it.

She was forever taking them out when she was around the house and then forgetting where she’d put them. ‘Where’s me teeth?’ was a familiar cry around the halls of Holly Grove. These peripatetic choppers would turn up in the most unlikely places, sometimes with embarrassing consequences.

In my teens, I’d go for a night on the razz, clubbing it over in Liverpool. If I’d managed to pull a bloke with a car, I’d try to convince him that giving me a lift home through the Mersey Tunnel would be well worth his time. Inevitably, such was my gratitude at being spared the hell of the tunnel bus, I would ask him in for a ‘cup of tea’ – a familiar euphemism for a grapple on the front-room couch, but a quiet one because my mum was upstairs in bed. During the preliminary necking session I would open one eye and to my utter mortification spy the Teeth, wedged down next to a cushion or grinning up at me obscenely from the pages of an upturned library book. As I tried to hide them by dropping them on the floor and pushing them under the sofa with my foot I’d be completely thrown off my stride.

Once I even found them biting into a toilet roll on top of the cistern and another time Jacko, a neighbour’s Labrador, a lovely, friendly old hound who had a habit of coming into the house and helping himself to anything he fancied, found her teeth on the side of the bath. ‘Where’s me bloody teeth?’ came the gummy enquiry just before she glanced at Jacko and had hysterics. Jacko was sat in the back yard gurning at her, his tail wagging, proudly showing off a muzzle full of false teeth.

Sometimes, as she sat on the sofa chatting and shaving an apple into wafer-thin membranes so that she could eat it with some semblance of dignity, the top set would unexpectedly slip their moorings and fall out into her lap, causing me, callous little swine, to fall about laughing. Sighing Garboesquely, she’d pick them up and, tossing them across the front-room floor, she’d moan, ‘These bloody teeth, why did I ever get them?’

In retrospect, I realize that she sometimes did the teeth act purely to entertain me.

I was born in the Tranmere Workhouse during a violent thunderstorm on 14 June 1955. That’s only partly true, I just fancied a bit of melodrama. I was actually born in St Catherine’s Hospital, which in its day had been a workhouse. The weather had been stormy but by the time I arrived at 7.30 a.m., a disgusting hour to make one’s debut, the storm had subsided and the sun was cracking the flags. According to my mother, the midwife who delivered me interpreted the storm clearing and the sun coming out as a promising omen. My mother, possessing an inherent pessimism, hoped that she was right.

St Cath’s was to feature heavily in the lives of our family. Operations for ulcers and varicose veins were performed there. My father died in St Cath’s after a heart attack. My sister nursed in maternity. My mother did a spell in the laundry and later she was an auxiliary nurse on the children’s ward – at least until the day the hated deputy matron, a vicious little gnome of a woman loathed by staff and patients alike, hit a child across its bare legs. Mum lost her temper and after she walloped Miss Brindle on the head with a bedpan she lost her job too.