A very french affair, p.1

A Very French Affair, page 1

Some names, places and identifying details have been changed to protect the identity of the individual.

First published in 2024

Text © Maria Hoyle, 2024

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Allen & Unwin

Level 2, 10 College Hill, Freemans Bay

Auckland 1011, New Zealand

Phone: (64 9) 377 3800

Email: auckland@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.co.nz

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

ISBN 978 1 991006 63 9

eISBN 978 1 76118 976 0

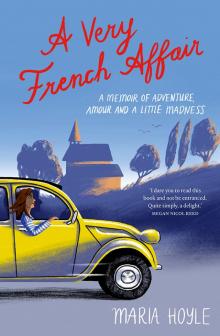

Cover illustration by Sophie Watson

Design by Katrina Duncan

Typeset in Heldane Text

For Lucy and Susanna

CONTENTS

1 Running Away to the Circus

2 The Arrival

3 Alistair and the Giant Misunderstandings

4 Les Voisins

5 Language Lessons

6 Les Amis

7 Brexit Stage Left

8 Autumn

9 Deuche Courage

10 Winter

11 ‘O Christmas Tree’

12 Are We There Yet?

13 Another Road Trip

14 Kia Ora, Auckland

15 It’s Just a Perfect Day

16 Fireworks

17 Le Mans

18 Drowning and Surfacing

19 Visa Day

20 More Fireworks

21 Clown

22 Beauty and the Beast

23 A Romantic and a Belated Pragmatist

24 Belonging

Acknowledgements

1

Running Away to the Circus

The air is warm and gentle, and the evening does what long, balmy summer evenings will. It casts a spell. Not that it needs to — this rural French setting is enchanting enough.

We’re in the grounds of a manor house — a grand edifice that’s peeling and faded but all the more charming for it. A makeshift bar runs across the great entrance to the house, selling wine, beer and plates of cured ham, cheese and bread still warm from the oven. The eccentric outdoor lighting — over-sized modern lampshades on wooden stands placed at intervals on the lawn — casts a glow over the scene.

We sip and we chat, heady on wine and excitement. Dogs stare hopefully at half-empty plates, and children squeal and chase one another among the wooden tables. On this sultry August evening, in a place that is more dimly lit theatre set than garden, it’s easy to believe in magic, in ghosts, in a night without end.

The manor house belonged to an old lady who stipulated that, on her death, it must never be sold but used for the public good. Its current residents are a troupe of actors who, in exchange for a peppercorn rent, perform shows throughout summer. In a yurt in the next field a ‘circus’ is to take place. Not a traditional circus but — it turns out — a theatre of the mind, where a simple trio of performers fires up our dormant imaginations, and we are all six years old again. On a tiny wooden stage, in the middle of a field, in the rural depths of France, I am transported. But then I already was.

I am living an existence I could barely have dreamed of five months ago. Back then, I was content enough with my life in Auckland. Content but also exhausted from surviving in an expensive city. It was a circus of sorts, and I was the resident juggler. How, I would think to myself, did I get to 63 and still find myself renting, working full-time, yet struggling to make ends meet? I was immensely grateful for my amazing daughters and friends. I was fully aware that my humdrum routine of Wordle, dog walks and early nights with my book was something families in war zones could only dream of. But I was also guiltily pondering: is this all there is?

I was online ‘dating’ — if you can call it that. You know, just in case. The same way some agnostics occasionally go to church. In truth I didn’t really see the point anymore. Married for seven years and now divorced, my past was littered with dashed hopes and failed romances … ex, ex, ex, ex, ex, ex — like a row of cold kisses.

It’s a wonder I was only slightly bruised and not wholly broken. I’d survived narcissists, depressives, control freaks and alcoholics. (Some people were all these things at once.) It’s not that I am flawless — heavens no. But I was spectacularly gifted at choosing men who’d flatter the bejesus out of me then inevitably, some months later, express disappointment that I wasn’t quite what they signed up for. In other words, that the five-foot package of positivity and delight they first encountered was showing herself to be something quite other — a woman with emotions, scars and needs. That regrettably, because of this, I wasn’t a fit for the role they’d had in mind. Consequently, going forwards, they felt cheerful and optimistic about the viability of their personal business without me.

My latest round of online dating only confirmed my worst suspicions. Every snapper-holding, singlet-wearing, Harley-straddling male deepened my despair. Every page of ghastly misspellings and arrogant list of deal-breakers (right up there ‘must be drama-free’) made my heart sink a little further.

And then I met Alistair.

We messaged each other intermittently, with weeks of silence in between. Then one night he left me a voicemail — and that was it. Some people have a thing about teeth, others hands, hair or a way of walking. For me it’s voices. Alistair’s was an exceptionally pleasant baritone — smooth and playful.

I also liked his approach to life, especially now that we had a lot less of it ahead. Alistair had an explorer’s spirit. He wanted to roam and discover — both geographically and in every other sense. He talked about Buddhism and spiritual growth, about travelling and trying new things. He exuded curiosity and dynamism, and I felt that in his company I could expand, not shrivel, as I aged.

He invited me to visit him in Nelson, in the South Island of New Zealand, where he was living until his move to France later in the year. He’d been in New Zealand for fifteen years but now his Irish–English roots beckoned and he was ready to go back to the northern hemisphere. ‘I own a mill by a river in France,’ he told me. ‘Of course you do,’ I said. Then I realised he meant it.

His return had been delayed because of Covid travel restrictions and he was eager to be reunited with this ‘truly special, magical’ place. Alistair told me all this straight away, so I knew it would be an extremely brief liaison. But I still had to go and meet him. Because, well, live for the moment, right? Besides, he fascinated me.

The two weekends we spent together were idyllic. E-bike rides, long lunches, afternoons lying on the grass down by the stream on his property, so much laughing and talking. But when he said ‘Why don’t you come to France too?’ it seemed insane. Nuts. Bonkers. People did that in romcoms. People who looked like Julia Roberts and Marion Cotillard did that. Not your average copywriter nearing retirement. Besides, the romantic prognosis wasn’t great. I was easily triggered, way too sensitive for my own good and terrible at intimacy. Not sex, but real intimacy. By what logic, then, did this have a chance of succeeding?

Yet what seemed more lunatic was the notion of spending my remaining healthy years in exactly the same way I had been doing for decades. Doing the nine-to-five grind, always short of money, living in the exact same postcode, with the exact same routine. The more I thought about France, the more sense it made.

I’d grown up in the UK, had family and friends in Europe, spoke French (rustily) and had no house to sell nor swathes of possessions to put in storage.

So I made up my mind to go and began cheerfully (somewhat hysterically) proclaiming to anyone who’d listen, ‘Guess what? I’m off to Fraaance!’ Without exception they marvelled at my courage, and I basked in their marvelling. Suddenly I wasn’t just Maria the short lady with a dog. I was Maria the Brave. Maria with a Plane Ticket to Paris.

Everyone was rooting for me. Even my employer was on board. I went into a Zoom meeting thinking I was about to resign from a job I loved, only to have my manager tell me: ‘No, wait. We can make this work. You can’t say no to an opportunity like this!’ We agreed I’d work part-time, remotely. This type of encouragement — often sprinkled with ‘Just do it,’ and ‘Oh wow, what an opportunity!’ — began to dismantle the barriers to making this huge life change.

In my heightened emotional state and believing my own ridiculous PR, if I’d been asked to pen an official press release on my decision, it would have gone something like this:

‘I want to prove that life — even in the third act — can still take surprising turns. That you can look forward to more than cheap bus fares and discounted movie tickets. That love is not only still possible, but it can be the best love you ever had. That maturity doesn’t need to be a stagnant pool where expectations go to die. It can be more like the river rushing below the windows of Alistair’s beloved mill — ever flowing, swirling, playing and tumbling towards its final destination. That — health allowing — you don’t need to do a slow fade but can live each day in glorious technicolour.’

Ha.

You see, it wasn’t quite that simple. Just because something makes sense doesn’t make it easy. Just because you’ve styled yourself as

In the weeks before my departure, I was in such danger of total emotional collapse I ought to have been red-stickered.

I couldn’t walk our beloved whippet without getting a knot in my throat when he tilted his beautiful grey head towards me. I couldn’t drive anywhere, or pass any park, restaurant, stretch of footpath, or even bus stop without sighing at some lovely memory attached to it. Sculptures I’d previously hated, inconvenient spots where my car had broken down, pretentious cafés I’d scoffed at … all were readily scooped up and forgiven. Even traffic cones.

Twenty-three years is a lot of deep roots to pull up. I’d invested years of emotional energy into settling in New Zealand, nurturing friendships, creating a whole new history and narrative. My daughters were just babies in matching gingham outfits when I first landed in Auckland with my Kiwi husband. And now, more than two decades on, Aotearoa was no longer a point on a map; it was in my DNA.

But France …

I’d been a Francophile long before I knew what one was. Even the blandness of my first French textbooks, when I was eleven, didn’t put me off. ‘Marie-Claire is in the garden, Maman is in the kitchen, Papa is at work.’ (It was the seventies, you understand). Come to think of it, Marie-Claire was never doing anything in the garden, just being. So very existentialist.

I didn’t get near France until I began studying French at university in my hometown of Manchester. And when I did finally make it — to Paris and later Lyon — I loved it all. The stinky cheeses, the fragrant boulangeries, the almost religious reverence for mealtimes, the pungent Gauloises cigarettes, the French way of shrugging and pouting, the pastis, the rillettes (a very fatty pork spread), the métro, the architecture.

That was all a lifetime ago, and I hadn’t been to France for well over 25 years. And now here it was, being offered up to me on a plate. Could I really say no?

There was one remaining, and significant, doubt. My daughters. They were my best friends in the world, and leaving seemed like a betrayal. But when I asked them to tell me honestly how they felt, they turned out to be my biggest cheerleaders: ‘Come on, Mum! It’s an adventure! You can always come back.’

When they saw me still wavering, they hit me with the one thing they knew would seal the deal. The phantom of regret.

‘Hey, we don’t want you sitting here when you’re seventy-three going, “Oh, I wonder how life would have been if I’d gone to France?” We’ll never hear the end of it!’

And there it was. That old cliché, ‘Life’s too short’, was no longer just a throwaway remark. It was the final nudge I needed to get on that plane.

2

The Arrival

If my ‘emotional reunion’ with Alistair were a scene in a movie, it would definitely require a second take. When I arrive at the train station, 50 minutes from my new French home, I am almost incoherent. Two plane marathons, endless interludes of queuing, and a three-hour train ride from Paris have left me worn out, wilted and wondering what’s so wrong with dating men, if not in my own postcode, then at least on the same side of the world.

But I am glad to see Alistair, after two months apart. I don’t so much embrace him as topple forwards into him like a felled pine tree. He smells nice. His hug is warm and his shirt is cool. I’d forgotten how tall he is.

He leads me to the station car park where his pretty blue Citroën 2CV is waiting and busies himself in the boot, producing first some water and a facecloth. I freshen up in full view of a café table of friends enjoying Wednesday-night beers in the setting sun. ‘I thought you hadn’t come,’ Alistair says as he rummages once more, this time emerging with a basket. ‘You were one of the last to get off the train and I thought, “She’s changed her mind”.’ I should have paid more attention to this remark. If I had, I might have avoided a looming mini-drama. More of that later.

In the basket are juicy flat peaches, camembert, a fresh baguette, fat green tomatoes and slivers of smoked salmon. We set off with the Citroën roof rolled back, gathering speed as we leave the town behind. The ‘deux chevaux’ bounces and occasionally rattles, and it’s like travelling through the countryside in a giant bread bin. I lift my face to the sky, let the peach juice dribble down my chin and the breeze whip through my hair. We race past fields of sunflowers that are radiant in the golden evening light, then we slow down as we snake through one tiny village after another. The landscape is ridiculously charming: rugged cream stone walls, ivy-clad barns, languid willows and pointy slate-turreted châteaux peeping over the horizon like overgrown pencils.

Alistair rests his tanned forearms casually on the wheel, and I try to take it all in. I can’t. It’s too beautiful, too idyllic. I will have to ingest it one morsel at a time, over the coming days and weeks.

It’s dark when we arrive at the moulin, but the full moon throws its spotlight on each charming detail. I’m smitten by it all … the craggy stone walls, the moulin’s shutters, even the old baked-bean can on a stick that warns visitors to steer clear of the ditch by the driveway. Most especially, I am hypnotised by the river, wobbling darkly beyond the trees: a blackcurrant jelly that’s not quite set.

But as I later climb the stairs to our bedroom, woozy on tiredness and chilled sparkling rosé, I become sharply aware of how far I am from everything I know. There is no sound but the rush of the river. No traffic, no people, not a bark or a siren or a bird call.

If this doesn’t work out, I will be adrift like a space traveller cut loose from her shuttle. I try not to think of my daughters back in New Zealand, of the dog wondering why I haven’t come home yet, of the 18,000 kilometres between me and everything I have loved for so long. I have to pull the shutters closed on these thoughts … otherwise I will drown.

Over the next week, I start to become accustomed to my new surroundings. Although ‘accustomed’ sounds a bit pedestrian. What I am actually doing is slowly waking, rubbing my eyes, and finding the illusion is still there.

I wake daily to what sounds like torrential rain, only to realise I’m in summer now and it’s just the rush of the river. As the heavy walnut furniture swims into view when I first open my eyes, I’m reminded with a jolt that this isn’t my own home. And as the duvet falls and rises gently next to me, I remember that I’m no longer single but living on the other side of the world with a man I met only months ago.

The sense of unreality is compounded by the shimmering heat and the long, hazy days. To arrive here in the heady midsummer is to step into a beautiful dream halfway through: one that is oscillating, unclear, mysteriously enchanting.

By midday we swelter, our skin glistens and one by one our intentions droop like week-old lettuce. No ‘Hmm, shouldn’t I be sorting my tax, taking up watercolour painting, signing up for online Pilates?’ No, no. It’s all out of the question. The heat comes along like a polite but firm butler to remove your shoes, relieve you of your ambitions and plans, plump up your pillows and leave you to get on with it. ‘It’ being seeking refuge in the river, flopping on the bed like a drowsy cat, or collapsing onto a sunlounger in the shade of the old walnut tree.

The moulin sits alongside the beautiful River Vienne, in the French department of the same name. And this tumbling mass of water is a godsend.

When the mercury hits the thirties, I pop on my water shoes and carefully descend the rough stone steps into the cool water. The current tugs at me as it roars past the mill, but it’s only kidding. It means no harm. As I make my way further in, it becomes calm again. Even the stones are hospitable, flat and wide like moss-covered ottomans. There’s one we call the Jesus Rock because it lies just below the surface so that when someone stands on it, they appear to be walking on water. Another rock is slanted, smooth and large enough for two — that’s the sunbathing rock.

The moulin itself is enchanting — a three-storey turret of cream and brown stone with bright blue wooden shutters and walls that are solid as eternity. A working flour mill for almost two centuries, it was turned into a rudimentary dwelling some fifty years ago. The first floor is our living and kitchen space, the upstairs the bedrooms. The millstones have retired — one to a life as a picnic table right outside the front door. The other has given itself up to being a layabout, languishing on the ground floor of the mill — a cool, musty space Alistair now uses as his workshop. This is where we enter our fortress — and when you bolt the great wooden door behind you at night, a great sense of safety and wellbeing descends.