Baf 43 discoveries in.., p.1

BAF 43 - Discoveries in Fantasy, page 1

part #44 of Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

05-07-2024

rework of an earlier version

Four “lost worlds”…

the worlds created by four remarkable writers, of which we here present what can be only a small sample of the richness, color, wit and excitement contained in the superlative writings of four highly imaginative gentlemen of letters.,

For fantasy is truly the playground of some of the finest writers and most fertile minds of all time, from Homer (and before) to the present. Except that in the old days, the mythmakers were dealing with the realities of their time, the monsters and magicks that made up their worlds were recognised as part of a real cosmos—and who knows, maybe they were right…

For Ballantine Books,

Lin Carter has written:

Lovecraft: A Look Behind the “Cthulhu Mythos”

Tolkien: A Look Behind “The Lord of the Rings”

And has edited these

anthologies & collections

At the Edge of the World / Beyond the Fields We Know /

The Doom That Came to Sarnath / Dragons, Elves, and Heroes /

The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath / Golden Cities, Far /

Hyperborea / New Worlds for Old / The Spawn of Cthulhu /

Xiccarph / The Young Magicians / Zothique.

DISCOVERIES

IN FANTASY

Edited,

with an Introduction and Notes, by

Lin Carter

BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK An Intext Publisher

Copyright © 1972 by Lin Carter

All rights reserved.

SBN 345-02546-6-095

This edition published by arrangement with the author’s agent,

Henry Morrison, Inc.

By Ernest Bramah:

“The Vision of Yin” was first published by the George H. Doran Company,

New York, 1900;

“The Dragon of Chang Tao” was first published by the

George H. Doran Company, New York, 1922.

By Donald Corley:

“The Bird With the Golden Beak” appeared in The Haunted Jester,

published by Robert M. McBride & Company, New York, 1931.

Copyright 1931 by Donald Corley;

“The Song of the Tombelaine” appeared in The House

of Lost Identity, published by Robert M. McBride & Company,

New York, 1927. Copyright 1927 by Robert M. McBride & Company.

By Eden Phillpotts:

“The Miniature” was first published in this country by

The Macmillan Company, New York, 1927.

First Printing, March, 1972

Printed in the United States of America

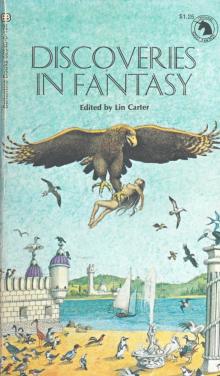

Cover art by Peter Le Vasseur

BALLANTINE BOOKS, INC.

101 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10003

This book, which attempts to revive interest in four

long neglected fantasy writers, I dedicate to James

Blish, who has for so very long done so much to revive

interest in another neglected writer known by the name of Cabell

Contents: ~

Introduction ~ Lost Worlds

Ernest Bramah

The Vision of Yin

The Dragon of Chang Tao

Richard Garnett

The Poet of Panopolis

The City of Philosophers

Donal Corley

The Bird with the Golden Beak

The Song of the Tombelaine

Eden Phillpotts

The Miniature

Lost Worlds

Some writers are born before their time and produce stories of great charm, beauty, and power for which the world is not quite ready or for which a readership has not yet evolved.

The fate of such writers is most unfortunate. They live in obscurity and die in neglect, and their stories vanish into the limbo of lost books. Such was the fate of the four authors represented in these pages.

Each writer created a world of his own on paper, but it was a fantasy world for which no audience could be found. Now, decades or generations after these authors wrote, the world is indeed ready for their particular kind of magic, but this recognition comes far too late to do them any good.

Ernest Bramah wrought an imaginary Chinese world and sang of its marvels in a delicious prose—ornate, bejeweled, polished, and sparkling with the wit of a Jack Vance. His fantasy-China is peopled with droll rogues, absurd magicians, weird dragons, and fat, complacent mandarins. He is an amazing writer.

Eden Phillpotts reconstructed a classical world to his own design and filled it with fauns and satyrs, gods and godlets, heroes and heroines, drawn from the Greek legends.

Donald Corley created a world entirely out of his own imagination, and with the sparkling gusto of a born Cabellian he playfully devised its history and geography and myths in a languorous prose that he footnoted with citations from invented books and impossible authorities.

Richard Garnett played with a multi-world drawn from a thousand sources—Greek, Chinese, Islamic, Roman, medieval—and created a gigantic book brimming with exquisite, gemlike little stories, perfect in miniature, like tiny cameos.

Each of these writers, however much or however little fame he won in his own time, has lapsed into the limbo of the forgotten, from which I have, sometimes with great difficulty, attempted to resurrect them. In some cases, so completely have they faded from knowledge that I have been able to find out only a very little about their lives.

Here are four lost worlds of fantasy, four forgotten masters brought back for a little while. Perhaps now their peculiar magics will find an audience that will not permit them to fade from view again.

From the very beginning of the Adult Fantasy Series, my publishers and I have eagerly sought out not only the great giants of fantasy—Morris, Eddison, Dunsany, Cabell, Tolkien—but the lesser known writers as well, such as Hope Mirrlees and Evangeline Walton. To the lesser-known group we now add four authors.

It is up to you, the readers, to say whether they shall live on or again fade back among the ranks of the forgotten.

—Lin Carter

Editorial Consultant:

The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Hollis, Long Island, New York

Ernest Bramah

The first of our forgotten masters is Ernest Bramah. So thoroughly has the world forgotten him that none of the authorities I consulted could give me the date of his birth, although from internal evidence in one of his early books it has been deduced as “about 1869.”

His real name was E. B. Smith, and he was an Englishman. His publisher, Grant Richards, recalls that he was actually discovered by the author E. V. Lucas. Lucas brought to the attention of Grant Richards “a careful typescript sewn into brown paper” that turned out to be the first draft manuscript of The Wallet of Kai Lung.

This Kai Lung, it seems, was a wandering storyteller in an imaginary China. Kai Lung was constantly getting into trouble and constantly getting himself accused of horrendous crimes, and in every case he managed to escape punishment by employing his tale-spinning talents very much in the same manner as another Oriental author of some repute named Scheherazade. It is these tales that make up the bulk of the four or five Kai Lung books. (I suspect this was merely a clever device Bramah employed to sell his short stories to publishers who did not want to publish short stories.)

At any rate, eight publishers had declined the honor of printing that first book about Kai Lung, but Grant Richards found it delightful reading and brought out the book himself. The reading public, alas, agreed with the eight other publishers, and at the end of seven publishing seasons the first edition (only one thousand copies, after all) still had not sold out.

I suppose it could truthfully be said that Ernest Bramah was born before his time. Others have remarked that the Kai Lung books are simply too clever and too subtle for a broad readership. They are caviar, and the readers are looking for meat and potatoes. Or least they were in Ernest Bramah’s day; by now, perhaps a larger number of readers have developed a taste for caviar.

Bramah had much better luck with his detective stories. He invented a blind detective, Max Carrados, and wrote some books about his exploits that were certainly more popular than the books about Kai Lung.

All of these books have been out of print for far too many years. It’s time something was done about this. So, this year we will be bringing back into print Kai Lung’s Golden Hours, which was first published in Great Britain in 1923. Watch for it.

According to Grant Richards, Ernest Bramah was the kindest and most amiable of men. Richards describes him as a small, bald man with twinkling black eyes. He seems also to have been a very shy man. When the editors of a dictionary of biographical data called Twentieth Century Authors asked him for some personal information, he replied, “I am not fond of writing about myself, and only in less degree about my work. My published books are about all that I care to pass on to the readers.”

This unseemly reticence is the reason I am unable to tell you the date of his birth with any degree of exactitude. Bramah lived in quiet retirement in the country and died at his country home in Somerset on June 27, 1942. The obituaries commonly gave his age as “about seventy-three,” and according to one of them he had lived, in China for many years.

This last item of information I strongly doubt. I suspect it was merely a good guess on the part of a busy obituary writer who had far too little factual data. For nothing of the authenti

Ernest Bramah’s China, then, is the fantastic bogus China of convention, not the real historical thing at all. He wrote of it in a prose so perfectly conceived that it becomes a miracle of style. As Hilaire Belloc once observed, the sly humor and philosophy of Bramah’s stories is a trick he achieves by pretending to adapt the flavor of Chinese literary conventions into the English. But the thing I love most about the tales is their irony and the brilliance of their wit. No matter how many angels or sages or divinities or dragons or enchanters pop up out of the ground in roiling clouds of perfumed green vapor, his placid mandarins and lovable rogues never lose their aplomb. A droll observation, a wry bon mot, a beautifully turned epigram is ever on their tongue, whatever the unexpected problem they have stumbled into.

—L.C.

The Vision of Yin

When Yin, the son of Yat Huang, had passed beyond the years assigned to the pursuits of boyhood, he was placed in the care of the hunchback Quang, so that he might be fully instructed in the management of the various weapons used in warfare, and also in the art of stratagem, by which a skillful leader is often enabled to conquer when opposed by an otherwise overwhelming multitude. In all these accomplishments Quang excelled to an exceptional degree; for although unprepossessing in appearance, he united matchless strength to an untiring subtlety. No other person in the entire Province of Kiang-si could hurl a javelin so unerringly while uttering sounds of terrifying menace, or could cause his sword to revolve around him so rapidly, while his face looked out from the glittering circles with an expression of ill-intentioned malignity that never failed to inspire his adversary with irrepressible emotions of alarm. No other person could so successfully feign to be devoid of life for almost any length of time, or by his manner of behaving create the fixed impression that he was one of insufficient understanding, and therefore harmless, It was for these reasons that Quang was chosen as the instructor of Yin by Yat Huang, who, without possessing any official degree, was a person to whom marks of obeisance were paid not only within his own town, but for a distance of many li around it.

At length the time arrived when Yin would in the ordinary course of events pass from the instructorship of Quang in order to devote himself to the commerce in which his father was engaged, and from time to time the unavoidable thought arose persistently within his mind that although Yat Huang doubtless knew better than he did what the circumstances of the future required, yet his manner of life for the past years was not such that he could contemplate engaging in the occupation of buying and selling porcelain clay with feelings of an overwhelming interest. Quang, however, maintained with every manifestation of inspired assurance that Yat Huang was to be commended down to the smallest detail, inasmuch as proficiency in the use of both blunt and sharp-edged weapons, and a faculty for passing undetected through the midst of an encamped body of foemen, fitted a person for the every-day affairs of life above all other accomplishments.

“Without doubt the very accomplished Yat Huang is well advised on this point,” continued Quang, “for even this mentally short-sighted person can call up within his understanding numerous specific incidents in the ordinary career of one engaged in the commerce of porcelain clay when such attainments would be of great remunerative benefit. Does the well-endowed Yin think, for example, that even the most depraved person would endeavour to gain an advantage over him in the matter of buying or selling porcelain clay if he fully understood, the fact that the one with whom he was trafficking could unhesitatingly transfix four persons with one arrow at the distance of a hundred paces? Or to what advantage would it be that a body of unscrupulous outcasts who owned a field of inferior clay should surround it with drawn swords by day and night endeavouring meanwhile to dispose of it as material of the finest quality, if the one whom they endeavoured to ensnare in this manner possessed the power of being able to pass through their ranks unseen and examine the clay at his leisure?”

“In the cases to which reference has been made, the possession of those qualities would undoubtedly be of considerable use,” admitted Yin; “yet, in spite of his entire ignorance of commercial matters, this one has a confident feeling that it would be more profitable to avoid such very doubtful forms of barter altogether rather than spend eight years in acquiring the arts by which to defeat them. That, however, is a question which concerns this person’s virtuous and engaging father more than his unworthy self, and his only regret is that no opportunity has offered by which he might prove that he has applied himself diligently to your instruction and example, O amiable Quang.”

It had long been a regret to Quang also that no incident of a disturbing nature had arisen whereby Yin could have shown himself proficient in the methods of defence and attack which he had taught him. This deficiency he had endeavoured to overcome, as far as possible, by constructing life-like models of all the most powerful and ferocious types of warriors and the fiercest and most relentless animals of the forests, so that Yin might become familiar with their appearance and discover in what manner each could be the most expeditiously engaged.

“Nevertheless,” remarked Quang, on an occasion when Yin appeared to be covered with honourable pride at having approached an unusually large and repulsive-looking tiger so stealthily that had the animal been really alive it would certainly have failed to perceive him, “such accomplishments are by no means to be regarded as conclusive in themselves. To steal insidiously upon a destructively-inclined wild beast and transfix it with one well-directed blow of a spear is attended by difficulties and emotions which are entirely absent in the case of a wicker-work animal covered with canvas-cloth, no matter how deceptive in appearance the latter may be.”

To afford Yin a more trustworthy example of how he should engage with an adversary of formidable proportions, Quang resolved upon an ingenious plan. Procuring the skin of a grey wolf, he concealed himself within it, and in the early morning, while the mist-damp was still upon the ground, he set forth to meet Yin, who had on a previous occasion spoken to him of his intention to be at a certain spot at such an hour. In this conscientious enterprise the painstaking Quang would doubtless have been successful, and Yin gained an assured proficiency and experience, had it not chanced that on the journey Quang encountered a labourer of low caste who was crossing the enclosed ground on his way to the rice field in which he worked. This contemptible and inopportune person, not having at any period of his existence perfected himself in the recognised and elegant methods of attack and defence, did not act in the manner which would assuredly have been adopted by Yin in similar circumstances, and for which Quang would have been fully prepared. On the contrary, without the least indication of what his intention was, he suddenly struck Quang, who was hesitating for a moment what action to take, a most intolerable blow with a formidable staff which he carried. The stroke in question inflicted itself upon Quang upon that part of the body where the head becomes connected with the neck, and would certainly have been followed by others of equal force and precision had not Quang in the meantime decided that the most dignified course for him to adopt would be to disclose his name and titles without delay. Upon learning these facts, the one who stood before him became very grossly and offensively amused, and having taken from Quang everything of value which he carried among his garments, went on his way, leaving Yin’s instructor to retrace his steps in unendurable dejection, as he then found that he possessed no further interest whatever in the undertaking.