Baf 22 golden cities f.., p.1

BAF 22 - Golden Cities, Far, page 1

part #22 of Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

16-07-2024

There is, perhaps, no reading matter so flagrantly devoted to pure pleasure as adult fantasy.

It has appeared in written form now for at least several hundred years, but the tradition of joy in the tales of man’s more impossible adventures and endeavors goes back far beyond written history. No country in the world is without its myths, its magic, its epic legends, its gods and heros of monumental stature.

Lin Carter writes with infectious enthusiasm about the origins and sources of the glittering array of fantasies he has collected in this volume—indeed, his joy in the discoveries he has made is at least as much fun to follow as the reading of each selection itself. And this joy is perhaps why these stories live, and have lived for centuries—in every age there have been those who loved the tales of the past and had the ability to share their love and to perpetuate the grand and glorious history of fantasy.

Other titles by Lin Carter

TOLKIEN: A LOOK BEHIND “THE LORD OF THE RINGS”

Anthologies edited by Lin Carter

DRAGONS, ELVES, AND HEROES

THE YOUNG MAGICIANS

GOLDEN CITIES, FAR

Other Adult Fantasy Titles

THE WOOD BEYOND THE WORLD by William Morris

THE SILVER STALLION by James Branch Cabell

LILITH by George MacDonald

FIGURES OF EARTH by James Branch Cabell

THE SORCERER’S SHIP by Hannes Bok

LAND OF UNREASON by Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp

THE HIGH PLACE by James Branch Cabell

AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD by Lord Dunsany

LUD-IN-THE-MIST by Hope Mirrlees

THE ISLAND OF THE MIGHTY by Evangeline Walton

THE SHAVING OF SHAGPAT by George Meredith

PHANTASTES by George MacDonald

THE DREAM QUEST OF UNKNOWN KADATH by H. P. Lovecraft

ZOTHIQUE by Clark Ashton Smith

THE WELL AT THE WORLD’S END, Vols. I & II by William Morris

DERYNI RISING by Katherine Kurtz

Adult

Fantasy

GOLDEN CITIES, FAR

Edited,

with an Introduction

and Notes,

by Lin Carter

BALLANTTNE BOOKS • NEW YORK

An lntext Publisher

Copyright © 1970 by Lin Carter

SBN 345-02045-6-095

All rights reserved.

First Printing: October, 1970

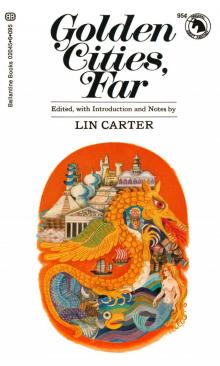

Cover art by Ralph Iwamoto and Kathleen Zimmerman

Printed in the United States of America

BALLANTTNE BOOKS, INC.

101 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003

“How Nefer-ka-ptah Found the Book of Thoth” (orig. “The Story of the Book of Thoth”) is from The Wisdom of the Egyptians by Brian Brown (New York, Brentano’s, 1928).

“The Descent of Ishtar to the Netherworld” is a segment from the unpublished poem Ishtar (freely rendered from the Sumerian Angalta Kigalsha) by Lin Carter. It appears here in print for the first time, and is copyright © 1970 by Lin Carter.

“The Talisman of Oromanes” is from Tales of the Genii, translated by Sir Charles Morell, a pseudonym of the Reverend James Ridley. The edition used here was published in London by George Bell in 1889.

“Wars of the Giants of Albion” is from the first book of the Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth; it is a new version of the 1718 Aaron Thompson translation, done especially for Golden Cities, Far by Wayland Smith; copyright © 1970 by Lin Carter.

“Forty Singing Seamen” is from Forty Singing Seamen and Other Poems by Alfred Noyes (New York, Frederick A. Stokes, 1906).

“The Shadowy Lord of Mommur” is an excerpt from Huon of Bordeaux, translated into English by Sir John Bourchier and retold by Robert Steele (London, George Allen, 1895).

“Olivier’s Brag” is from The Merrie Tales of Jacques Tournebroche by Anatole France, translated by Alfred Allinson. The text used here is taken from The Works of Anatole France, Vol. III (New York, Parke, Austin and Lipscomb, n.d.).

“The White Bull” is from The Best Known Works of Voltaire, (New York, Literary Classics, Inc., n.d.). The name of the translator is unknown.

“The Yellow Dwarf” is from The Blue Fairy Book, edited by Andrew Lang and originally published in London in 1889. The text used here is from an edition published by A. L. Burt, New York, n.d.

“Arcalaus the Enchanter” is from the First Book of Amadis of Gaul, translated by Robert Southey (London, John Russell Smith, 1872), and “The Isle of Wonders” is from the Second Book of the same romance.

“The Palace of Illusions” was translated from the Italian epic Orlando Furioso of Ludovico Ariosto especially for its appearance in this book. Copyright © 1970 by Richard Hodgens.

With respect and affection,

I dedicate this compendium

of ancient marvels to

FRITZ LEIBER,

one of the finest living masters

of heroic fantasy

Lin Carter

Contents

Here There Be Dragons - An Introduction

PART I - FROM THE ANCIENT EAST

Introduction to the First Tale:

How Nefer-Ka-Ptah Found the Book of Thoth

Introduction to the Second Tales

The Descent of Ishtar to the Netherworld

PART II - THE WORLD OF THE ARABIAN NIGHTS

Introduction to the Third Tale:

Prince Ahmed and the Fairy Paribanon

Introduction to the Fourth Tale:

The Talisman of Oromanes

PART III - MEDIEVAL LORE AND LEGEND

Introduction to the Fifth Tale:

Wars of the Giants of Albion

Introduction to the Sixth Tale:

Forty Singing Seamen

PART IV - THE CAROLINGIAN CYCLE

Introduction to the Seventh Tale:

The Shadowy Lord of Mommur

Introduction to the Eighth Tale:

Olivier’s Brag

PART V - FABULISTS AND FAIRY TALES

Introduction to the Ninth Tale:

The White Bull From

Introduction to the Tenth Tale:

The Yellow Dwarf

PART VI - THE GREAT ROMANCES

Introduction to the Eleventh and Twelfth Tales:

Arcalaus The Enchanter

The Isle of Wonders

Introduction to the Thirteenth Tale:

The Palace of Illusions

A CONCLUDING WORD

Here There Be Dragons

An Introduction

… geographers … crowd into the edges of their maps

parts of the world which they do not know about, adding

notes in the margin to the effect that beyond this lies nothing

but sandy deserts full of wild beasts, unapproachable bogs,

Scythian ice, or a frozen sea.

—Plutarch: Lives, Theseus

The less you know about a thing, the more eager you are to listen to somebody’s extravagant accounts of it and its marvels.

Our ancestors knew hardly anything about geography, but the map makers had to put something in those big blank spots. Sometimes they just wrote the name of the country or continent in large calligraphy and filled in the empty places with flourishes and curlicues. On other occasions they sketched in tiny pictures of the Tower of Babel, or Noah’s Ark neatly perched on a mountain peak, or Gog and Magog locked up behind the Caucasus.

And once in a while a bored or playful cartographer, confronted with a blank space in, say, the great Gobi Desert or Further Tartary, would lean forward and carefully letter-in “Heere ther bee Dragones” or some other morsel of editorial commentary.

Firsthand information was hard to come by in those days. Our ancestors knew next to nothing about the planet they happened to be living on, for the very good reason that it was still mostly unexplored. But that never stopped anyone from making up tall tales of distant marvels.

Take the shape of the earth itself. Anaximander, who made his reputation as a Thinker by importing the sundial into Greece, said it was cylindrical.

That old bean-hater Pythagoras said it was obviously a sphere.* Somebody called Henricus thought it might be oval.

* Actually, he came the closest. The earth is a kind of sphere, a sphere flattened at

both poles: technically, an “oblate spheroid.”

And a rather colorful 6th Century a.d. Egyptian topped them all. He was called Cosmas Indicopleustes, which means “he-who-went-to-India,” or something like that, and he was convinced the earth was rectangular like the top of a table.

This Cosmas was a successful traveling salesman who retired from business and got religion. He became a monk and wrote a book called Christian Topography, which must be the most insane geography book of all time. As the authority for his tabletop theory, he scorned all profane sources of data and went straight to Holy Writ. St. Paul once called the world “God’s tabernacle,” you see, and elsewhere the scriptures said your standard tabernacle, or altar, should be two cubits long and one cubit wide. From this Cosmas extrapolated that the world was flat as a board, rectangular, and exactly twice as long from east to west as it was from north to south. (And with sharp comers, I assume.)

Luckily, no one paid much attention to Cosmas Indicopleustes, because everybody had his own idea, and these got wilder as time went on. Wildest of all was a theory of one Matthew of Paris. This sa

Maps in those days were most intriguing. Based on vague hints in classical authors, or rumors derived from the occasional traveler who may or may not ever have actually been there, or just on their own imaginations, the old geographers filled up their charts with a number of countries that were not really there at all and probably never had been.

The Empire of Prester John was a favorite and, depending on which geographer you preferred, this country was on the marches of Cathay, or somewhere in India, or down at the tail end of Africa.

The land of the Cimmerians was also popular. It was usually up on top of Scythia, or way over beside Hyperborea, or on the shores of the Frozen Sea. The Cimmerians—who turned up in the 20th century in Robert E. Howard’s popular stories of Conan the Barbarian—were actually made up by old blind Homer. He seems to have invented them by getting the Welsh Cymry tribes confused with an obscure pack of nomads called the Gimri. As the Gimri were supposed to dwell north of the Black Sea, Homer and later writers assigned the imaginary nation of Cimmeria to that general region.

Atlantis showed up on some of the older maps too, despite the fact that Plato, who was the first to talk about it, said it had been destroyed ages before. It kept turning up for many centuries, and last made an appearance, I believe, in 1678 a.d., on a map published by Athanasius Kircher, a brainy Jesuit who had a private theory about everything in (or out of) the world, obviously including Atlantis.

Atlantis lay due west of the Pillars of Hercules, where few people had been, so it was safe to put it on maps. But even places somewhat better traveled, like India, were not very realistically depicted. And the further away you got, the fewer the restrictions on creative thinking…

For example, south of India lay the magical island of Taprobane, or Serendib. South of that stretched the mighty waters of the Indian Ocean, or as they used to call it in those days, the Erythraean Sea.

This sea was, of course, filled with a variety of nautical monstrosities. One such was the Fastitocalon, a sort of awfully big whale who liked to snooze on top of the ocean with most of him under the surface and just his back above the waters. He was so big that his back alone was as big as an island, and frequently was mistaken for one. In fact, the Fastitocalon was constantly being landed on by sea-weary mariners hungry for a bit of terra firma. They usually did not discover their mistake until after they had built a bonfire on his back with the sun-dried seaweed and driftwood with which his enormous bulk was bedecked. Awakening to find himself on fire, the Fastitocalon, not unnaturally, would crash-dive to the ocean floor—generally taking the hapless mariners down with him. (But not always; sometimes they got back to their ship in time to sail away unscathed, as did our old friend Sinbad on his first voyage.)

Another spectacular denizen of the Erythraean Sea was the Aspidochelone, a king-sized turtle who had the sweetest breath in Creation. So sweet, in fact, that all he had to do for lunch was cruise along the surface with his mouth open, and the fish, delighted by the odor of his breath, swam right in by the solid ton. This was definitely not the safest of all seas to sail!

Below all this was a colossal continent of marvels called Terra Australis Incognita, or the Unknown Southland, for the excellent reason that nobody had ever been there. Which, of course, hardly stopped people from talking about it.

The Unknown Southland has quite an amusing history. Originally, it was called Antichthon or sometimes, Antipodea. The cartographer Oronce Fine renamed it Terra Australis on his 1531 world map, and the name stuck. The idea of there being such a place dates back to another one of those Greek wise men called Hipparchus of Bithynia. (Who flourished, if that’s really the word I want, around 146-127 B.C.)

He sounds to me like a thoroughly unlikable, quarrelsome, hardheaded old pedant. Once he got an idea into his head, it was there to stay, and he was not about to change his mind to please anybody. Most of Hipparchus’ books are lost by now, but we know a lot about his ideas because people like Strabo and Claudius Ptolemy were always quoting him. Especially Ptolemy, who thought him quite a brain and stole most of his stuff for his own Almagest.

We don’t know much about Hipparchus’ career, but he seems to have been constantly getting into fights with other philosophers. He had violent opinions about Eratosthenes; he was dead set against the “new” astronomy that had sprung up since Alexander the Great; he thought Aristarchus of Samos was a fool and his heliocentric theory hogwash (as a matter of fact, the theory was absolutely true); and at some point, Hipparchus got the wrong idea about the tail end of Africa. He figured that it curved around the other way and ran along underneath the Indian Ocean.

Eventually he decided that Africa ran all the way to China and was a part of it, making the Indian Ocean a land-locked sea. Since you could hardly call this Africa-to-China land bridge either “Africa” or “China”, a new name had to be devised: hence Antichthon, Antipodea, and later on, Terra Australis Incognita.

When Ptolemy came along he bought the whole idea— lock, stock and barrel. And so did everybody after Ptolemy. Then somebody decided Terra Incognita wasn’t a part of Africa or China after all. Oh, it was there, all right, but it was a full-blown island continent of its own, not just the bottom part of one.

This idea of a separate continent south of everything else perhaps arose because of Pythagoras. He promulgated the idea (actually, a rather pretty idea), that the gods, being perfect, could create only perfection; and Pythagoras’ idea of perfection was that everything balanced equally.

Hence if you had a map with Europe, Asia, and Africa in the top half, it ought to be balanced with the same amount of real estate in the bottom half. Thus, by the 5th century A.D., we have Macrobius’ world map showing Terra Incognita as big as Asia, Africa and Europe rolled into one.

The more imaginative geographers vied with each other in making up facts about this fantasy continent. It was a lush tropical country filled with flowers, they said. The streets were paved with gold; the women were not only gorgeous but went around without any clothes on; and diamonds and emeralds were as common as pebbles on the beach. One of the later map-makers, Ortelius, added the most picturesque detail of all: Terra Incognita, said he, abounded in parrots as big as horses. (Actually, he said, “Psittacorum regio . . . ob incredibilem earem avium ibedem magnitudinem.” A whopper like that one is enough to sink most imaginary continents on the spot.)

Tune passed. Terra Incognita got bigger and fancier and more detailed. Beside the giant parrots and all those naked women, it was by now adorned with exquisitely detailed rivers and mountain ranges and so on, just like a real country … despite the fact that nobody had ever been there.