Baf 38 the water of th.., p.1

BAF 38 - The Water of the Wondrous Isles, page 1

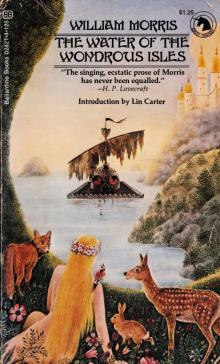

part #38 of Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

01-07-2024

William Morris

The nineteenth century artist, sculptor, musician, master of all trades and jack of none, is at his brilliant best in this tale of shining waters and shrouded magic.

His gentle and spirited heroine, Birdalone, steps forth into the world as freshly and gaily as when Morris first committed her to the written page. Her courage carries her into a remarkable series of all too human adventures despite the wonders and marvels that abound in her enchanted world.

Morris uses the honest reality of human relationships and emotions to point up the magicks with which his rich imagination em’ broiders the story. Equally, the loves and an” gers, the longings and jealousies of his people are thrown into sharp relief by the somber threat of the Sending Boat in which Bird” alone travels or the mad witchery of the Isle of Unsought Increase. Throughout he main” tains that mark of the master storyteller—the need to keep turning the page to find out what is going to happen next …

Also by William Morris

WELL AT THE WORLD’S END, Volume I

WELL AT THE WORLD’S END, Volume II

WOOD BEYOND THE WORLD

Adult

Fantasy

PUBLISHED IN

BALLANTINE BOOKS

ADULT FANTASY EDITIONS

THE WATER OF

THE WONDROUS

ISLES

William Morris

Introduction by

Lin Carter

BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK

An Intext Publisher

Introduction Copyright © 1971 by Lin Carter

All rights reserved.

SBN 345-02421-4-125

First Printing: November, 1971

Printed in the United States of America

Cover art by Gervasio Gallardo

BALLANTINE BOOKS, INC.

101 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10003

Contents:~

INTRODUCTION ~ About THE WATER OF THE WONDROUS ISLES,

and William Morris:

THE FIRST PART: OF THE HOUSE OF CAPTIVITY

THE SECOND PART: OF THE WONDROUS ISLES

THE THIRD PART: OF THE CASTLE OF THE QUEST

THE FOURTH PART: OF THE DAYS OF ABIDING

THE FIFTH PART: THE TALE OF THE QUEST’S ENDING

THE SIXTH PART: THE DAYS OF ABSENCE

THE SEVENTH PART: THE DAYS OF RETURNING

About THE WATER OF THE WONDROUS ISLES, and William Morris:

Birdalone

He loved Medievalism, old prose romance, and Norse poetry. He hated the industrial age, modernity, and bad taste. He invented the Morris chair, wove tapestries and rugs, designed wallpaper and books, and introduced Socialism, the glories of Icelandic saga-literature, and the pre-Raphaelites to his century. He wrote some of the best poetry of the Victorian Era, printed the most beautiful book of his age (the Kelmscott Chaucer), and, almost in passing, invented the fantasy novel.

But listen to William Morris as he tells his own story, in a letter to fellow-Socialist Andreas Scheu on the fifth of September, 1883.

I was born at Walthamstow in Essex, in March 1834, a suburban village on the edge of Epping Forest, and once a pleasant place enough, but now terribly cocknified and choked up by the jerry-builder. My father was a businessman in the city, and well-to-do; and we lived in the ordinary bourgeois style of comfort; and since we belonged to the evangelical section of the English Church I was brought up in what I should call rich establishmentarianism puritanism; a religion which even as a boy I never took to.

I went to school at Marlborough College, which was then a new and very rough school. As far as my school instruction went, I think I may fairly say I learned next to nothing there, for indeed next to nothing was taught; but the place is in very beautiful country, thickly scattered over with prehistoric monuments, and I set myself eagerly to studying these and everything else that had any history in it, and so perhaps learned a good deal, especially as there was a good library at the school to which I sometimes had access. I should mention that ever since I could remember I was a great devourer of books. I don’t remember being taught to read, and by the time I was seven years old I had read a very great many books good, bad, and indifferent.

My father died in 1847, a few months before I went to Marlborough; but as he had engaged in a fortunate mining speculation before his death, we were left very well off, rich in fact.

I went to Oxford in 1853 as a member of Exeter College; I took very ill to the studies of the place; but fell-to very vigorously on history and especially medieval history … I was a good deal influenced by the works of Charles Kingsley.”

Before long, Morris fell in with young men of similar interests, young men who, like himself, were later to become very famous men indeed—like the painter Burne-Jones, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the poet. Between them they founded the pre-Raphaelite movement, reviving an interest in Gothic architecture and medieval handcrafts, which was to leave a powerful mark on the history of Victorian design, architecture, ornament and jewelry, and which served to pave the way for the even greater movement called Art Nouveau.

William Morris is considered today chiefly important as a pre-Raphaelite artist and a pioneer Socialist. We tend to overlook his great role in bringing the mighty saga-literature of the North to the attention of his contemporaries. It was Morris the translator who gave to the English-speaking world great, trail-blazing versions of Beowulf, the Volsunga Saga, Grettir the Strong, the Nibelungenlied, and other literary masterworks from early Germanic, Icelandic, and Anglo-Saxon literatures.

Morris was truly one of the last “Renaissance men,” a man whose intellectual and artistic interests—and attainments— touched upon the broadest possible range of subjects. His translations from the ancient Northern epics and sagas were sufficient to have made a lasting reputation for any man; but he went far beyond this: although it is not generally remembered these days, he also translated the Aeneid into English verse, and subsequently wrote a verse epic of his own, The Life and Death of Jason, the theme of which is based on Greek myths.

In 1888, he published the first of a series of prose romances, and a historical novel about Saxons battling against the invading legions of Rome,The House of the Wulfings. In 1894, he turned from history to pure fantasy and invented the pseudo-medieval world-scape of his first great heroic fantasy novel—also the world’s first fantasy novel, for that matter—The Wood Beyond the World (which we revived for the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series in 1969).

His next novel was The Water of the Wondrous Isles, published in 1895, the same year as his translations of Beowulf and the Heimskringla. The last years of his life were splendidly productive. 1896 saw the birth of his masterpiece, The Well at the World*s End, the longest fantasy novel written before the advent of Tolkien. No one can say where Morris might have turned next, nor with what even more glorious fantasies he might have exceeded his own accomplishments. That must rest forever among many unanswerable speculations. For on October 3, 1896, after publishing the last of his prose romances and seeing through the press his masterwork of book design, the Kelmscott Chaucer, William Morris died at the age of sixty-two. He was buried on the grounds of his own home, Kelmscott House.

The romances of William Morris are long out of print and forgotten by most people. The historians of nineteenth-century English literature generally tend to ignore them, while according Morris a paragraph or two in their books for his poetry.

The only people who remember Morris’s novels are devotees like C. S. Lewis and L. Sprague de Camp and myself: modem fantasy writers with a scholarly bent, interested in the development of our favorite genre. De Camp and I have been mentioning William Morris in essays, introductions, anthologies and letters for some years now. Morris is of the greatest historical importance to the evolution of the imaginary-world novel, for it is our thesis that he was its inventor. Beyond this critical significance, of course, he is also a delightfully entertaining writer, with a singing medieval style many readers find delicious.

When Ballantine Books decided to establish the adult Fantasy Series in 1969 with myself as editor, I was enthusiastic over the possibilities. I have been immersed in the literature of the fantastic since boyhood and have long been familiar with most of the literary milestones and famous writers in the field, and the opportunity to bring fine old books back into print again, in large popular editions priced inexpensively enough so that everyone could enjoy them, was most exciting.

One of the writers I was eager to revive was William Morris. Only through reading his great fantasy romances can one understand the origin of modem works such as The Lord of the Rings or Fletcher Pratt’s The Well of the Unicom. These books did not, like Athena, spring full-blown from the brow of their authors: they are recent additions to a fine old tradition founded seventy-seven years ago when The Wood Beyond The World was first published.

But without a familiarity with Morris one cannot realize this fact, and Morris was long out of print. Whenever de Camp or I would refer to these pioneering fantasy epics, we drew a blank response from our readers, few of whom knew of Morris at all, and then only as a Socialist or Victorian designer. (In fact, now that I think of it, I was the one who originally drew L. Sprague de Camp’s attention to the significance of the novels of William Morris in the history of the imaginary-world fantasy.)

With the publication of The Water

Nor is this book the last of William Morris you will see: currently, with the assistance of members of The William Morris Society (an English organization, mainly, but with members in North America), I am engaged in hunting down some short prose romances with an eye towards assembling them into a book for the Series in a year or two.

The William Morris Society, incidentally, was founded on September 13, 1955 when a letter inviting inquiries from persons interested in William Morris appeared in The Times of London, under the signatures of J. Brandon-Jones, Nikolaus Pevsner, and Stanley Morison. The Society is active in reawakening interest in the many-sided talents of William Morris. In 1957, they arranged a public exhibition of his typographical work; the Society also encourages the modem manufacture of his textile and wallpaper designs, and arranges tours to places of interest to Morris enthusiasts.

If you would like to explore more deeply the career and talents of William Morris, you might be interested in the Journal which the Society publishes twice a year. For further details you should write to the Honorary Secretary, The William Morris Society, 260 Sandycombe Road, Kew, Surrey, England.

The full importance and lasting value of Morris’s three great fantasy novels has yet to be seen. In such books as The Water of the Wondrous Isles, the wanderings and adventures of Birdalone permit the reader to explore the misty fields and shadowy forests of an invented world-scape more similar to the dim world of Sir Thomas Malory than that of any other writer’s.

Morris conceived of the notion of a story laid in a world made up by its author, but based on the kind of world and age described by the romancers of the Middle Ages. This was his principal innovation, and it was a fertile one. Following his example, other writers have created worlds drawn from medieval models—Poul Anderson in The Broken Sword, Fletcher Pratt in The Well of the Unicom, and C. L. Moore with her tales of Jirel of Joiry.

Fantasy writers have turned Morris’s discovery to new directions. Robert E. Howard, Henry Kuttner, and myself have explored invented worldscapes of remoter antiquity; Jack Vance, A. E. Van Vogt (in The Book of Ptath), and S. Fowler Wright have done the same sort of thing for the very distant future. And there have been other experiments, such as Fletcher Pratt’s imaginary version of the eighteenth-century Austrian Empire depicted in his novel The Blue Star (which we published in the Series in 1969). And Lord Dunsany adapted the concept to the short story form, and employed largely Oriental world-models for his marvelous tales included in my edition of At The Edge of The World, which we published last year.

All of these later writers and their books descend from the tradition of William Morris. Fantasy writers have no patron saint, but if there were one, it would be the gifted gentleman of Kelmscott House—William Morris.

—Lin Carter

Editorial Consultant:

The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Hollis, Long Island, New York

THE FIRST PART: OF THE HOUSE OF CAPTIVITY

CHAPTER I. CATCH AT UTTERHAY

Whilom, as tells the tale, was a walled cheaping-town hight Utterhay, which was builded in a bight of the land a little off the great highway which went from over the mountains to the sea.

The said town was hard on the borders of a wood, which men held to be mighty great, or maybe measureless; though few indeed had entered it, and they that had, brought back tales wild and confused thereof.

Therein was neither highway nor byway, nor wood-reeve nor way-warden; never came chapman thence into Utterhay; no man of Utterhay was so poor or so bold that he durst raise the hunt therein; no outlaw durst flee thereto; no man of God had such trust in the saints that he durst build him a cell in that wood.

For all men deemed it more than perilous; and some said that there walked the worst of the dead; othersome that the Goddesses of the Gentiles haunted there; others again that it was the faery rather, but they full of malice and guile. But most commonly it was deemed that the devils swarmed amidst of its thickets, and that wheresoever a man sought to, who was once environed by it, ever it was the Gate of Hell whereto he came. And the said wood was called Evilshaw.

Nevertheless the cheaping-town throve not ill; for whatso evil things haunted Evilshaw, never came they into Utterhay in such guise that men knew them, neither wotted they of any hurt that they had of the Devils of Evilshaw.

Now in the said cheaping-town, on a day, it was market and high noon, and in the market-place was much people thronging; and amidst of them went a woman, tall, and strong of aspect, of some thirty winters by seeming, black-haired, hook-nosed and hawk-eyed, not so fair to look on as masterful and proud. She led a great grey ass betwixt two panniers, wherein she laded her marketings. But now she had done her chaffer, and was looking about her as if to note the folk for her disport; but when she came across a child, whether it were borne in arms or led by its kinswomen, or were going alone, as were some, she seemed more heedful of it, and eyed it more closely than aught else.

So she strolled about till she was come to the outskirts of the throng, and there she happened on a babe of some two winters, which was crawling about on its hands and knees, with scarce a rag upon its little body. She watched it, and looked whereto it was going, and saw a woman sitting on a stone, with none anigh her, her face bowed over her knees as if she were weary or sorry. Unto her crept the little one, murmuring and merry, and put its arms about the woman’s legs, and buried its face in the folds of her gown: she looked up therewith, and showed a face which had once been full fair, but was now grown bony and haggard, though she were scarce past five and twenty years. She took the child and strained it to her bosom, and kissed it, face and hands, and made it great cheer, but ever woefully. The tall stranger stood looking down on her, and noted how evilly she was clad, and how she seemed to have nought to do with that throng of thriving cheapeners, and she smiled somewhat sourly.

At last she spake, and her voice was not so harsh as might have been looked for from her face: Dame, she said, thou seemest to be less busy than most folk here; might I crave of thee to tell an alien who has but some hour to dwell in this good town where she may find her a chamber wherein to rest and eat a morsel, and be untroubled of ribalds and ill company? Said the poor-wife: Short shall be my tale; I am over poor to know of hostelries and ale-houses that I may tell thee aught thereof. Said the other: Maybe some neighbour of thine would take me in for thy sake? Said the mother: What neighbours have I since my man died; and I dying of hunger, and in this town of thrift and abundance?

The leader of the ass was silent a while, then she said: Poor woman! I begin to have pity on thee; and I tell thee that luck hath come to thee to-day.

Now the poor-wife had stood up with the babe in her arms and was turning to go her ways; but the alien put forth a hand to her, and said: Stand a while and hearken good tidings. And she put her hand to her girdle-pouch, and drew thereout a good golden piece, a noble, and said: When I am sitting down in thine house thou wilt have earned this, and when I take my soles out thereof there will be three more of like countenance, if I be content with thee meanwhile.

The woman looked on the gold, and tears came into her eyes; but she laughed and said: Houseroom may I give thee for an hour truly, and therewithal water of the well, and a mouse’s meal of bread. If thou deem that worth three nobles, how may I say thee nay, when they may save the life of my little one. But what else wouldst thou of me? Little enough, said the alien; so lead me straight to thine house.