Baf 31 vathek, p.1

BAF 31 - Vathek, page 1

29-06-2024

“VATHEK is a tale of the grandson of the

Caliph Haroun, who, tormented by an ambition

for super-terrestrial power, is lured by an evil

genius to the subterranean throne of the mighty

and fabulous pre-Adamite sultans in the fiery

halls of Eblis, the Mahometan devil …”

—H. P. Lovecraft

It is also the best Oriental fantasy ever written, a living monument to a remarkable man whose only literary work it proved to be.

William Beckford’s personal life was certainly no less extraordinary than the fantasy lives of the heroes he learned to worship in the volumes of The Arabian Nights he pored over.

Perhaps this is why his own fanciful effort displays such a rich understanding of the essence of imaginative writing.

Adult Fantasy

RECENT BALLANTTNE ADULT FANTASY

TITLES

With Introductions by Lin Carter

THE MAN WHO WAS THURSDAY

G. K. Chesterton

DON RODRIGUEZ: CHRONICLES OF SHADOW VALLEY

Lord Dunsany

HYPERBOREA

Clark Ashton Smith

RED MOON AND BLACK MOUNTAIN

Joy Chant

SOMETHING ABOUT EVE

James Branch Cabell

The History of the Caliph

VATHEK

Including the Episodes of Vathek

An Arabian Tale by

WILLIAM BECKFORD

with the Original Notes

Introduction by

Lin Carter

BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK

An Intext Publisher

Copyright © 1971 by Lin Carter

SBN 345-02279-3-095

All rights reserved.

First Printing: June, 1971

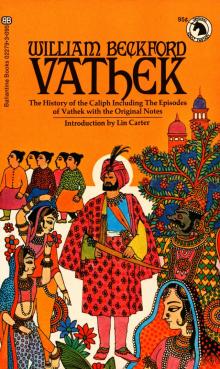

Cover Art by Ray Cruz

Printed in Canada,

BALLANTINE BOOKS, INC.

101 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003

Contents:-

Introduction ~ About VATHEK and William Beckford:

Vathek

The Story of Prince Alasi and The Princess Firouzkah

The Story of Prince Barkiarokh

The Story of the Princess Zulkaïs and the Prince Kalilah

Notes

About VATHEK and William Beckford:

The Caliph of Fonthill Abbey

Most authors live fairly dull, unexciting lives, spending most of their time hunched over typewriters and bits of paper. How refreshing, therefore, to find one whose own life was as fantastic as one of his own characters!

William Beckford was a spectacular eccentric, a colossal and glittering celebrity. It is hard to write even the briefest account of his life without employing a plethora of exclamation points, but I shall try.

Beckford was born in 1760. His great-grandfather was Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica. When his grandfather died, he left behind him a fortune of £300,000. His father, twice Lord Mayor of London, once picked a fight with King George HE on the floor of Parliament. Through his mother, Beckford was descended from every Magna Carta baron except those who had died without issue.

At the age of eleven he inherited a staggering fortune, which left him the wealthiest commoner in England. At seventeen, he toured Holland, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Mozart was his music teacher; his portrait was painted by Romney; he received the blessings of Voltaire at Femey. That year he published his first book, a witty and satirical study of famous painters, which caused him to be praised as a literary prodigy.

Everything he did was a little larger than ordinary life size. At twenty-two, he wrote a novel in French in only three days and two nights. To date, the work has seen 189 years and shows no signs of aging. At twenty-three, Beckford married the noblewoman Lady Margaret Gordon, who died while giving birth to their second daughter. He subsequently traveled in Spain and Portugal, then returned to England where he built the most incredible house you ever heard of.

What can I say about Fonthill Abbey? It had a stone wall around it 12 feet high and 8 miles long. The rooms were equally fantastic; one of diem, the Brown Parlour, measured 56 feet from wall to wall, while the Long Gallery—an apt name, if ever there was one—measured 330 feet The door into the main hall was quite spectacular, too; it was 35 feet high, and the hinges alone weighed over a ton.

Then of course there was the Tower. Beckford wanted a tower, and he got one: 300 feet of tower, possibly the tallest structure in all Wiltshire. Five hundred men, working day and night, built it only to have it topple over immediately. Beckford remained unruffled; his only complaint was that he had not been there to see it fall. He ordered another one built The second tower was more modest in its proportions, just 276 feet tail. It didn’t fall down until 1822, and Beckford had sold Fonthill by then, and moved to Lansdowne Hill near Bath, and was building yet another one.

To say that Fonthill was quite a house Is to be over-modest. Beckford spent £273,000 in fitting it out (He later sold it for £330,000.) It contained a magnificent library; most of the books had previously belonged to kings, queens, popes, or cardinals. To flesh it out a bit, Beckford bought the entire library of Gibbon—you know—the Gibbon of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Beckford lived on a prodigious scale, like someone out of the Arabian Nights. When you have £1 million in the bank, and an income of £100,000 a year, you can afford nice things. He died in his eighties and his daughter married a duke.

The only really important thing about William Beckford is Vathek. It is the greatest Oriental fantasy novel ever written, perhaps the best-written and most enjoyable of all the early Gothic Romances. In fact, I will go even further and say that there are very few English novels from 1785 of any genre or description, that have aged so little and are still so much fun to read today.

The earl of Chatham, his father’s friend, advised a tutor to keep young Beckford from reading the Arabian Nights, but the boy would not be restrained. He did not just read the Arabian Nights; he wallowed in it, and never forgot it Thus was the seed of Vathek sown in fertile soil, to flower a few years later when Beckford was twenty-two.

The great novels which have been written by twenty-two year old authors can probably be counted on the fingers of one hand. The odd thing about Vathek, however, is not that it was written by a boy of twenty-two, but that he never wrote a second novel. Imagine being able to write an immortal masterpiece so young…and never writing a second one! But then, Beckford did not like to repeat himself. He never did anything more than once—except, of course, for building towers.

Vathek is a thing of mystery, a nexus of curious anecdotes, a center of controversy and scandal, and a book with a remarkable history.

Its first edition was a pirated translation. Beckford had written the novel in French. (This is not particularly unusual; Oscar Wilde wrote Salomi in French, and, in our time, Samuel Beckett, an Irishman like Wilde, writes in French.) A year earlier, Beckford had met an English clergyman, the Reverend Samuel Henley, an Orientalist Their friendship, and Henley’s enthusiasm for Eastern literature, seems to have prompted Beckford to turn his boyhood love for the Arabian Nights into a bizarre oriental novel.

Towards the end of Vathek, there is a passage where the young lovers, the Caliph Vathek of Baghdad and the Princess Nouronihar, are wandering through the dark halls of the Subterranean Palace of Eblis (the devil). Beckford planned to insert here three long stories, told to the lovers by other mortal inmates of the Palace of Subterranean Fire. The novel itself was, of course, written first—in three days and two nights; it is not impossible that in the white heat of inspiration a novel of some forty thousand words could be so swiftly composed. The tales, though, were another matter; he tinkered with them for approximately four years.

Henley completed his translation of the novel, and then was forced to sit and wait patiently, year after year, while Beckford fiddled around with the tales, waiting for the rest. Eventually, his patience was exhausted.

While the first edition was being set in France, with Beckford puttering endlessly over it, Henley—without authorization—jumped the gun and rushed his own English translation of Beckford’s novel into print And I’m afraid Henley didn’t put any name on it but his own. There was a bit of scandal over this, as you might imagine.

Since his name was omitted in the English edition, the only way poor Beckford could lay claim to bis own creation was to rush his French original into print without the tales which were not yet finished. The French edition of Vathek was published in 1787. The scandal, and the controversy that followed, is literary history.

In the flurry of excitement, the tales disappeared from sight and were forgotten. They were believed lost in manuscript, for they were never published.

A trifle more than a century passed. Around 1909, an English biographer named Lewis Melville, collecting documents for his Life and Letters of William Beckford of Fonthill, examined the Beckford papers preserved in Hamilton Palace by Beckford’s descendant, the Duke of Hamilton. Among die papers he found the original manuscripts of the three tales, ’The Story of Prince Alasi and the Princess Firouzkah,”

“The Story of Prince Barkiarokh,” and “The Story of the Princess Zulkaïs and the Prince Kalilah.” They had lain there, neglected and forgotten, for over a hundred years.

Melville received permission from the Duke to have them published and they were printed in 1909 and 1910. Eventually, they were translated into Engl

Never have the Episodes been inserted into any edition of Vathek ever published! That is, not until this one. I have often puzzled over the obtuseness of publishers and editors. It has now been fifty-nine years since The Episodes of Vathek appeared in English, but never has it occurred to anyone to put them into Vathek where they belong, where they were intended to go from the very beginning.

Why this should be so I simply cannot say; but from the day we established this Adult Fantasy Series I determined to edit an edition of Vathek which contained the three tales in their proper place. This has now been done, and so, 189 years after it was first written, Vathek appears in print in its complete form just as William Beckford intended it

Many writers have admired Vathek, and some have been influenced by it Perhaps you will already have read our Adult Fantasy Series edition of George Meredith’s oriental phantasmagoria, The Shaving of Shagpat, published in 1970. Meredith read Vathek with great pleasure, and paid it the supreme compliment of not imitating it Shagpat is comical, bawdy, and heavily written. Vathek is a delirium of deliciously erotic and gorgeous fantasy; it was written with a light hand and is graceful rather than heavy, decadent, or eerie. But Shagpat could not have been written without the example of Vathek; the two stand together as the best oriental fantasies written by European authors.

H. P. Lovecraft admired Vathek and praised it in his famous essay, “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” first published in 1927. He seems particularly to have admired Vathek‘s oriental flavor of exaggeration, saying,

The descriptions of Vathek’s palaces and diversions, of his scheming sorceress-mother Carathis and her witch-tower with the fifty one-eyed negresses, of his pilgrimage to the haunted ruins of Istakhar…of primordial towers and terraces in the burning moonlight of the waste, and of the terrible Cyclopean halls of Eblis, where, lured by glittering promises, each victim is compelled to wander in anguish forever…are triumphs of weird colouring which raise the book to a permanent place in English letters.

Lovecraft’s friend, correspondent, and fellow Weird Tales writer, dark Ashton Smith, also found Vathek very much to his taste; so much so that he attempted a translation of the third “Episode”. It was published in the magazine Leaves, but did not reach a large audience until it was included in a collection of his tales called The Abominations of Yondo (Arkham House, 1960).

Beyond this translation, Smith seems to have been deeply fascinated by Vathek. A short story, “The Ghoul” (1934), is laid in Baghdad during the reign of Beck-ford’s Caliph. Those few critics who have written on Smith’s prose return again and again to Vathek (and also to “The Masque of the Red Death” by Poe), helpless to find any other analogue to his bejeweled and mordant prose. Personally, I think Clark Ashton Smith derived much of his prose style from Vathek; it has always seemed to me that if ever Smith had written a novel, it would have been a Vathek.

One last note; this one from history. (I think this the first time in all of the dozens of Introductions I have written for this Series, that I must add such a note.) Curious as it may seem, there was a real Caliph Vathek. The Caliph Harun al-Wathik, ninth monarch of the Abbasid dynasty, ruled from 842 to 847; he was succeeded by his brother Ja’far, called al-Mutawakkil. You will find more data on al-Wathik’s reign in your Encyclopaedia Britannica, under “Caliphate.”

In building his extravagant phantasmagoria around a genuine historical personage, Beckford was, without being aware of it, in the classic tradition of the school of the Gothic Romance. This school was founded by Horace Walpole with a bizarre horror tale called The Castle of Otronto; there really is a castle at Otronto. Hie two most famous Gothic romances of all, Frankenstein and Dracula, also contain a kernel of historical fact; there was, and is to this day, a Baron Frankenstein, a Castle Frankenstein, and a town of Frankenstein, as in the old Karloff movies. And there once really was a Count (Vaivode, actually) Dracula and a Castle Dracula; although the Count bore little resemblance to the late Bela Lugosi

Here, then, is the best oriental fantasy ever written, published in paperback for the first time in the United States, and complete with its long-lost “Episodes” for the first time anywhere. One hundred and eighty-nine years old at this writing, it has lost none of its deliciously bizarre charm. I, for one, hope it will remain alive to delight generations of readers to at least another equal span of time.

—Lin Carter

Editorial Consultant:

The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Hollis, Long Island, New York

Vathek

Vathek, ninth Caliph of die race of the Abassides, was the son of Motassem, and the grandson of Haroun A1 Raschid.

From an early accession to the throne, and the talents he possessed to adorn it, his subjects were induced to expect that his reign would be long and happy. His figure was pleasing and majestic; but when he was angry one of his eyes became so terrible that no person could bear to behold it, and the wretch upon whom it was fixed instantly fell backward, and sometimes expired. For fear, however, of depopulating his dominions and making his palace desolate, he but rarely gave way to his anger.

Being much addicted to women and the pleasures of the table, he sought by his affability to procure agreeable companions; and he succeeded the better as his generosity was unbounded and his indulgences unrestrained, for he was by no means scrupulous, nor did he think with the Caliph Omar Ben Abdalaziz that it was necessary to make a hell of this world to enjoy Paradise in the next

He surpassed in magnificence all his predecessors. The palace of Alkoremmi, which his father Motassem had erected on the hill of Pied Horses and which commanded the whole city of Samarah, was in his idea far too scanty; he added therefore five wings, or rather other palaces, which he designed for the particular gratification of each of his senses.

In the first of these were tables continually covered with the most exquisite dainties, which were supplied both by night and by day according to their constant consumption, whilst the most delicious wines and the choicest cordials flowed forth from a hundred fountains that were never exhausted. This palace was called ’The Eternal or Unsatiating Banquet.’

The second was styled The Temple of Melody, or The Nectar of the Soul.’ It was inhabited by the most skilful musicians and admired poets of the time, who not only displayed their talents within but, dispersing in bands without, caused every surrounding scene to reverberate their songs, which were continually varied in the most delightful succession.

The palace named ’The Delight of the Eyes, or The Support of Memory* was one entire enchantment. Rarities collected from every comer of the earth were there found in such profusion as to dazzle and confound, but for the order in which they were arranged. One gallery exhibited the pictures of the celebrated Mani, and statues that seemed to be alive. Here a well-managed perspective attracted the sight, there the magic of optics agreeably deceived it; whilst the naturalist on his part exhibited, in their several classes, the various gifts that Heaven had bestowed on our globe. In a word, Vathek omitted nothing in this palace that might gratify the curiosity of those who resorted to it, although he was not able to satisfy his own, for he was of all men the most curious.