Baf 05 lilith, p.1

BAF 05 - Lilith, page 1

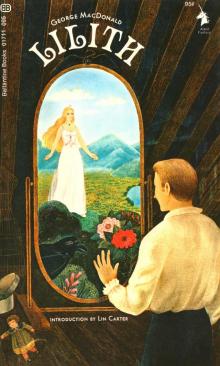

part #5 of Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

17-06-2024

“In his power to project his

inner life into images, events,

beings, landscapes which are

valid for all, he is one of the

most remarkable writers of the

nineteenth century…and

‘Lilith’ is equal if not superior

to the best of Poe.”

W. H. Auden

In any time, the writing of George MacDonald would be remarkable, even brilliant. But for his own time, in his century, the depth of his inner vision is nothing less than extraordinary. Somewhere in this conservative ex-Minister of seemingly genial disposition there lurked a daemon of negation. LILITH is proof that he was able to express this in evocative and visionary prose for it is the tale of man in a nightmare, forever reaching for the unspeakably beautiful, eternally elusive dream.

Adult

Fantasy

Introduction by Lin Carter

BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK

Introduction © 1969 by Lin Carter

First Ballantine Books edition: September, 1969

Printed in Canada

BALLANTINE BOOKS, INC.

101 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10003

About LILITH and George MacDonald

The Land Beyond the Hidden Door

It was a large rather ugly house, set back, a little from the shore of the Thames, at Hammersmith. And it was one of the most famous houses in England—“Kelmscott House”—where the brilliant, eccentric, richly talented William Morris lived. He was to be remembered for many things: his translations of Norse sagas, his impact on Victorian art and decoration, his poetry, and his novels. And among these were books like The Wood Beyond the World and The Well at the World’s End—books of quests and strange adventures in imaginary medieval worlds of magic and mystery. Books that were to found the school of modern adult fantasy and influence such later writers as Lord Dunsany, E.R. Eddison, C.S. Lewis, Fletcher Pratt and J.R.R. Tolkien.

But the huge, ugly old house had another claim to fame. Years before William Morris lived there it had another name—“The Retreat” In those days, around 1872, a retired Scots minister, his wife, and their eleven children lived in the big house. The minister’s name was George MacDonald and it was in this house that he wrote two children’s books that were to make his name ever-young: At the Back of the North Wind, and The Princess and the Goblin.

He was an extraordinary man. Born the son of a farmer in Aberdeenshire in 1824, he took degrees in chemistry and natural philosophy at the university and became a Congregationalist minister and a surprisingly successful one. Then, when only twenty-six, he retired to devote the rest of his long life to literature. He was enormously successful at that, too. His first book, a long poem called Within and Without, was an immediate success and won the admiration of Tennyson and Lady Byron. He went on to write dozens of other books—some popular novels of Scots peasant life, eight fairy tale books for children, two of the most brilliant adult fantasy novels ever written, and even several volumes of collected sermons and theological studies (which were to win an enthusiastic admirer in C.S. Lewis, who edited a two-volume anthology of them).

He became celebrated, famous, popular. His close friends included the greatest literary7 figures of his time, Ruskin, Tennyson, Lewis Carroll. He was a world traveler, equally at home in cosmopolitan London or exotic Algiers, who topped his career with a tremendously successful lecture tour of America. Happily married, he raised a huge family; and seems to have had a perfectly delightful and rewarding life. As Florence Becker Lennon put it, in her biography of his good friend, Lewis Carroll: “His life, both artistic and familial, seems to have been uniformly happy and fruitful, and he died at an advanced old age [in 1905, at eighty-one], surrounded by an adoring family.”

A Mystical Genius of Faerie Romance

If you were to knock on the door of The Retreat, and be ushered into the great living room which was really two rooms made into one, you would find yourself shaking hands with a large, genial, ebulliently happy man. “Great, tall, handsome…with a fine head of hair and a thick beard turning to white, though it had once been of the darkest black,” is how Roger Lancelyn Green, our contemporary authority on fantasy in children’s literature, describes him. He had deep-set, luminous, sea-blue eyes, sparkling, frosty, keen. He spoke with the warm, resonant voice of an actor (which, in fact, he was; he and his wife and their older children produced ambitious dramas all over England, such as Macbeth, and a version of Pilgrim’s Progress written by his wife.)

He would invite you to sit down, but he probably would not offer you anything stronger to drink than tea, because of his strict Calvinist upbringing. While he rang for tea you might glance curiously at the huge mass of untidy manuscript heaped atop the great desk under the windows. It might be one of his own books in the making, or something by one of his famous writer-friends. It might even be the original manuscript of Alice, for Lewis Carroll lent it to his friend MacDonald, begging his opinion, and MacDonald read it aloud to his children. Their instant love for the story—his son Greville said it was so good there should be sixty thousand more volumes of it!—may have been a deciding factor in persuading Carroll, the shy, gawky, stuttering Oxford don, to have it published.

By all accounts, MacDonald was a healthy, manly, robust, serene and happy man, despite the chilly, primitive surroundings in which he grew up. His relationship with his father seems to have been one of warm and rare companionship; he grew up among animals and loved them all his life; his childhood, despite the strict, religious aspect, was a wonderful time. Riding, climbing, swimming, fishing to his heart’s content, listening to peasants tell old, old tales of the fairies who lived in dark mountain caves and the wild kelpies at the bottom of the tarns.

From his Scots ancestry, MacDonald inherited the wild romantic mysticism of the Highlands, and he combined this with a remarkable and apparently intuitive grasp of psychological truths that were far ahead of his time. His books are deep and strong, even the fairy tales and the dream romances, such as Lilith and Phantasies. Woven into their texture is? natural love and knowledge of the wild, dark moors of the Scottish earth, the weird lore of the ancient, superstitious Scots blood, a deep and sincere belief in the Divine, an inner faith that went beyond mere Christian orthodoxy. They are written with a rich, multi-layered style that blends straight storytelling with symbolic overtones and hidden levels of allegory that give even his children’s stories a depth, a wisdom, and a strength that has kept them alive for almost a century.

About “Lilith” and “Phantasies”

His two adult fantasies are Lilith and Phantasies. The latter, subtitled A Faerie Romance, is very much a young author’s first book. It was published in 1858 and it was his first novel. The sources and influences (Bunyan, for example) are all too obvious; the narrative strained to drive home the symbolic level. It is difficult to read.

But Lilith is something else. It was written very late in life, in 1895, ten years before his death. The writing is mature and sophisticated. The story seizes your attention, ignites your imagination, holds your interest. It is profound and moving, haunted with shadowy figures, filled with bright, mocking faces, illuminated with flashes of stark and terrible and thrilling imaginative force. Its psychological perception and use of dream symbols is amazing, and bears close comparison with the best of Kafka.

So, of the two. we have chosen Lilith to publish first in the Adult Fantasy Series. As you begin it, as you fall under the darkly brilliant spell of a writer of prodigious imaginative power, as he seizes and transports you through the secret door in the back of the closet and thence into a wild, strange, weirdly beautiful World Beyond, you will begin to understand why.

The setting is worthy of Poe at his highest intensity. A young student home from Oxford prowls his vast ancestral home. It is a structure of tremendous antiquity, haunted by shadows of the past. He feels drawn to the ancient, labyrinthine library. Wandering through the crowded shelves he perceives a dim, unknown figure. In the stifling silence he” follows it until it vanishes into a closet. Therein he finds a hidden door and, passing through, he enters upon a mysterious world…a shadowy, symbolic world of waking dream…

Lilith is a very unusual and stimulating book. It has had an enormous influence on later writers. C.S. Lewis, who in his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, admits the three greatest influences on his life were the music of Wagner, the works of William Morris, and the two dream romances of George MacDonald, borrowed that going-through-the-secret-door-in-back-of-the-closet scene for The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the first of his marvelous Narnia books. And David Lindsay, author of that extraordinary novel A Voyage to Arcturus, found much in MacDonald to use. W. H. Auden is a modern enthusiast, and has written widely on MacDonald’s works. And Professor Tolkien read him in his youth. Although he now repudiates any conscious influence of MacDonald on The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings, many readers glimpse the ugly, grisly, subterranean and light-loathing Goblins of MacDonald’s two Curdie books behind Tolkien’s Orcs (which were originally called “Goblins” in early editions of The Hobbit, although they have since been renamed Orcs).

Do not read MacDonald, consciously hunting for meanings to the allegories. As W.H. Auden writes, in an Afterword to one of George MacDonald’s fairy tales, “To hunt for symbols in a fairy tale is absolutely fatal.” It kills the magic and robs you of the greater part of your pleasure. Immerse yourself in the book,

Then the Old man of the Earth stooped over the floor of the cave, raised a huge stone from it, and left it leaning. It disclosed a great hole.

“That is the way” he said.

“But there are no stairs!”

“You must throw yourself in.

There is no other

way.”

—LIN CARTER

Editorial Consultant:

The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Hollis, Long Island, New York.

Contents

The Land Beyond the Hidden Door

1 - The Library

2 - The Mirror

3 - The Raven

4 - Somewhere or Nowhere?

5 - The Old Church

6 - The Sexton’s Cottage

7 - The Cemetery

8 - My Father’s Manuscript

9 - I Repent

10 - The Bad Burrow

11 - The Evil Wood

12 - Friends and Foes

13 - The Little Ones

14 - A Crisis

15 - A Strange Hostess

16 - A Gruesome Dance

17 - A Grotesque Tragedy

18 - Dead or Alive?

19 - The White Leech

20 - Gone! — But How?

21 - The Fugitive ‘Mother

22 - Bulika

23 - A Woman of Bulika

24 - The White Leopardess

25 - The Princess

26 - A Battle Royal

27 - The Silent Fountain

28 - I Am Silenced

29 - The Persian Cat

30 - Adam Explains

31 - The Sexton’s Old Horse

32 - The Lovers and the Hags

33 - Lona’s Narrative

34 - Preparation

35 - The Little Ones in Bulika

36 - Mother and Daughter

37 - The Shadow

38 - To the House of bitterness

39 - That Night

40 - The House of Death

41 - I Am Sent

42 - I Sleep the Sleep

43 - The Dreams that Came

44 - The Waking

45 - The Journey Home

46 - The City

47 - The Endless Ending

LILITH

1

The Library

I had just finished my studies at Oxford, and was taking a brief holiday from work before assuming definitely the management of the estate. My father died when I was yet a child; my mother followed him within a year; and I was nearly as much alone in the world as a man might find himself.

I had made little acquaintance with the history of my ancestors. Almost the only thing I knew concerning them was, that a notable number of them had been given to study. I had myself so far inherited the tendency as to devote a good deal of my time, though, J confess, after a somewhat desultory fashion, to the physical sciences. It was chiefly the wonder they woke that drew me. I was constantly seeing, and on the outlook to see, strange analogies, not only between the facts of different sciences of the same order, or between physical and metaphysical facts, but between physical hypotheses and suggestions glimmering out of the metaphysical dreams into which I was in the habit of falling. I was at the same time much given to a premature indulgence of the impulse to turn hypothesis into theory. Of my mental peculiarities there is no occasion to say more.

The house as well as the family was of some antiquity, but no description of it is necessary to the understanding of my narrative. It contained a fine library, whose growth began before the invention of printing, and had continued to my own time, greatly influenced, of course, by changes of taste and pursuit. Nothing surely can more impress upon a man the transitory nature of possession than his succeeding to an ancient property! Like a moving panorama mine has passed from before many eyes, and is now slowly flitting from before my own.

The library, although duly considered in many alterations of the house and additions to it, had nevertheless, like an encroaching state, absorbed one room after another until it occupied the greater part of the ground floor. Its chief room was large, and the walls of it were covered with books almost to the ceiling; the rooms into which it overflowed were of various sizes and shapes, and communicated in modes as various—by doors, by open arches, by short passages, by steps up and steps down.

In the great room I mainly spent my time, reading books of science, old as well as new; for the history of the human mind in relation to supposed knowledge was what most of all interested me. Ptolemy, Dante, the two Bacons, and Boyle were even more to me than Darwin or Maxwell, as so much nearer the vanished van breaking into the dark of ignorance.

In the evening of a gloomy day of August I was sitting in my usual place, my back to one of the windows, reading. It had rained the greater part of the morning and afternoon, but just as the sun was setting, the clouds parted in front of him, and he shone into the room. I rose and looked out of the window. In the center of the great lawn the feathering top of the fountain column was filled with his red glory. I turned to resume my seat, when my eye was caught by the same glory on the one picture in the room—a portrait, in a sort of niche or little shrine sunk for it in the expanse of book-filled shelves. I knew it as the likeness of one. of my ancestors, but had never even wondered why it hung there alone, and not in the gallery, or one of the great rooms, among the other family portraits. The direct sunlight brought out the painting wonderfully; for the first time I seemed to see it, and for the first time it seemed to respond to my look. With my eyes full of the light reflected from it, something, I cannot tell what, made me turn and cast a glance to the farther end of the room, when I saw, or seemed to see, a tall figure reaching up a hand to a bookshelf. The next instant, my vision apparently rectified by the comparative dusk, I saw no one, and concluded that my optic nerves had been momentarily affected from within.

I resumed my reading, and would doubtless have forgotten the vague, evanescent impression, had it not been that, having occasion a moment after to consult a certain volume, I found but a gap in the row where it ought to have stood, and the same instant remembered that just there I had seen, or fancied I saw, the old man in search of a book. I looked all about the spot but in vain. The next morning, however, there it was, just where I had thought to find it! I knew of no one in the house likely to be interested in such a book.

Three days after, another and yet odder thing took place.

In one of the walls was the low, narrow door of a closet, containing some of the oldest and rarest of the books. It was a very thick door, with a projecting frame, and it had been the fancy of some ancestor to cross it with shallow shelves, filled with book-backs only. The harmless trick may be excused by the fact that the titles on the sham backs were either humorously original, or those of books lost beyond hope of recovery. I had a great liking for the masked door.

To complete the illusion of it, some inventive workman apparently had shoved in, on the top of one of the rows, a part of a volume thin enough to lie between it and the bottom of the next shelf: he had cut away diagonally a considerable portion, and fixed the remnant with one of its open corners projecting beyond the book-backs. The binding of the mutilated volume was limp vellum, and one could open the corner far enough to see that it was manuscript upon parchment.