Baf 01 the blue star, p.1

BAF 01 - The Blue Star, page 1

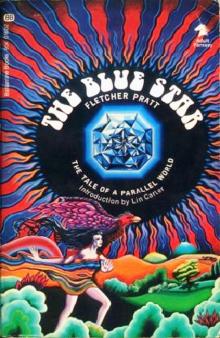

part #1 of Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

13-06-2024

Reworking of ab earlier version

ADULT FANTASY

SUPPOSE, FOR A MOMENT, THAT WITCHES WERE REAL …

Well, as a matter of fact, of course, they are. There was a time, indeed (although not in our own timestream), when witchcraft was the recognized repository of scientific knowledge—when witches wielded a power, nowever reluctantly, which, if it did not threaten other sciences, certainly frightened established religion.

There was this about the science of witchcraft, that it could not be taught to anyone who had not inherited the ability to learn, and inheritance came through the female line only. Thus Lalette Aster-hax, daughter of the witch Leonalda, could not escape either the power or her destiny. She was well aware that this made her a target, indeed, that being a witch would put her life in danger. And moreover there were the onerous duties which she would like to have escaped. Nothing would have pleased Lalette more than to have been a simple maiden, loved and loving.

She did her best to achieve this unworthy end— and thereby wound herself into a contortion of adventures that even a witch was not equipped to deal with …

THE

BLUE STAR

by

Fletcher Pratt

Introduction by Lin Carter

BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK

Copyright 1952 by Twayne Publishers, Inc.

Introduction copyright © 1969 by Lin Carter

All Rights reserved, No portion of this book may be copied

without prmission except brief quotations embodied in

articles or reviews.

First Ballantine Printing : May, 1969

Printed in the United States of America

BALLANTINE BOOKS, INC.

101 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003

Contents:

Introduction - About the Author by Lin Carter

Prologue

Chapter 1 Netznegon City: March Rain

Chapter 2. April Night

Chapter 3. Escape

Chapter 4. Daylight; Refuge

Chapter 5. Night; Generosity; Treason

Chapter 6. Night and Day; The Place of Masks

Chapter 7. Sedad Vix: A New Life

Chapter 8. High Politic

Chapter 9. Spring Festival: Intrigue of Count Cleudi

Chapter 10. Prelude to the Servants’ Ball

Chapter 11. Kazmerga; Two Against a World

Chapter 12. Netznegon City; A Zigraner Festival

Chapter 13. Farewell and Greeting

Chapter 14. The Eastern Sea; The Captain’s Story

Chapter 15. Charalkis; The Door Closes

Chapter 16. The Eastern Sea: Systole

Chapter 17. Charalkis: The Depth and Rise

Chapter 18. Decide for Life

Chapter 19. Two Choices

Chapter 20. Inevitable

Chapter 21. Midwinter: The Return

Chapter 22. The Law of Love

Chapter 23. Netznegon: Return to Glory

Chapter 24. Speeches in the Great Assembly

Chapter 25. Interview at the Nation’s Guest-House

Chapter 26. The Court of Special Cases

Chapter 27. Winter Light

Chapter 28. Embers Revived

Chapter 29. No and Yes

Epilogue

The Blue Star

About

THE BLUE STAR

and Fletcher Pratt

Knavery in Netznegon

When you hear the word “fantasy,” do you automatically think of children’s books, fairy tales, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz? If so, the title of this new Series—“Adult Fantasy”— may sound like a contradiction in terms. But such is not the case at all.

Some of the most sophisticated novels of the last two centuries have been fantastic romances of adventure and ideas; books which few, if any, children would be capable of appreciating. The astonishing success of J. R. R. Tolkien’sThe Lord of the Rings, and Ballantine Books’ editions of Mervyn Peake’sGormenghast trilogy and the extraordinary fantastic novels of E. R. Eddison have proved beyond a doubt that an enthusiastic adult audience exists for fantasy novels of adult calibre. The trouble is that many of these books are long out of print, scarce and rare, known only to a handful of collectors and connoisseurs. Some of them have never been published in the United States and are difficult to find.

The Parallel World of Fletcher Pratt

The Blue Star is a perfect example of what we mean by Adult Fantasy. It was first published in 1952, two years before the first British edition of Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring.

Pratt was a hard-headed, practical-minded and canny professional writer and historian, an authority on U.S. naval history, the Civil War and medieval Denmark. He was also an enthusiastic connoisseur of what I call “epic fantasy”—the huge, crowded novel of warfare, quest and adventure which takes place in . an imaginary pre-industrial age worldscape of the author’s own invention. But Pratt was impatient with hasty writers and ill-conceived imaginary worlds. No devotee of the Sword and Sorcery tale, he loathed swashbucklers such as Robert E. Howard’s “Conan” or John Jakes’ “Brak the Barbarian,” or my own character, “Thongor of Lemuria.” His friend and collaborator, L. Sprague de Camp, informs me, “He hated heroes who simply batter their way out of traps by means of bulging thews, without bothering to use their brains.” He wanted realistic, self-consistent fantasy worlds; worlds in which the author really sat down and thought things through with logic and intelligence and a firm grounding in historical minutia. He would have scoffed at Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom, where warriors roam the dead sea bottoms armed with terrific radium-powered rifles— but somehow seem to do all their fighting with swords. Instead, Pratt preferred to use the classic construction of postulating the presence (or the absence) of given conditions or facts and then extrapolating a likely, world—whenever or wherever, in reality or the imagination, such a world might exist. He discusses this in a rather wooden opening to The Blue Star—but then his world itself flowers into vivid life.

The world of the Empire and its capital, Netznegon, the scene of The Blue Star, is Pratt’s idea of what a fantasy world should be, can be, but all too often is not. No purple and gold and crimson universe where anything can happen, Pratt’s world is roughly parallel to our own. Gunpowder has not been discovered, but magic works; science is a fable, but witchcraft, as a repository of power and knowledge is real— as, of course, are witches. No barbaric, gorgeous worldscape with walled stone cities, improbably luscious princesses, incredibly stalwart sword-swinging heroes and amazingly villainous villains, Pratt’s world is clearly similar to our own at a slightly earlier age.

The period is obviously modelled closely on the Austriar Empire of the eighteenth century—say, the reign of Maris Theresa: we find ourselves in a tawdry, decadent Empire! beginning to totter toward collapse, rotten from within, shaken with the currents of revolutionary change.

Pratt’s hero is a bored, dissatisfied and rather ineffectualyoung man named Rodvard Bergelin, who holds a dull clerical job in the government genealogical offices in Netznegon. Rodvard becomes embroiled in a secret revolutionary society, a political organization called the Sons of the New Day, who chafe at the inequalities of inherited titles, landed gentry and hereditary castes, and dream of pulling the whole corrupt, crumbling Empire down and building a brave new world on its ruins.

How to Make a Witch

Magic works in Pratt’s parallel world. A caste of hereditary witches exists, barely tolerated by the established State religion, whose chief pontiff, the “Episcopal,” takes a dim view of such goings-on. The power of witchcraft is passed down from mother to daughter, according to Pratt’s fairly complicated system. The transfer takes place in the moment when the nubile young witch is deflowered: mother loses the ability and daughter gains it. The daughter’s lover, by the way, gets use of a peculiar aspect of this power: he takes possession of her talismanic charm, a five-pointed azurine jewel, the “Blue Star” of the title, and with it can read the true emotions of any person by looking into his or her eyes. The Sons of the New Day bully our bored young clerk-hero, Rodvard, into seducing a virgin witch named Lalette Aster-hax, so that he will be able to use the power of her star to further their Bolshevik-type political schemes.

Now, Rodvard is not at all in love with the skinny and shrewish-tempered witch-girl: he has his dreams pinned on a lush baron’s daughter who has been dropping around the genealogical offices of late. And Lalette is not impressed with him, either: she enters into this rather distasteful and coldblooded liaison in order to escape the attentions of a repulsive rake named Count Cleudi, a womanizing blueblood who fancies himself an irresistible Casanova. Almost at once the whole sordid affair goes wrong and the “lovers” flee the city to become mixed up in a series of adventurous escapes, near-traps and perilous tight spots. I will not spoil the story for you by detailing it any further.

A Forgotten Fantasy Masterpiece

Fletcher Pratt was born in 1897 and died in 1956, only four years after this novel was published. In a long and fruitful collaboration with L. Sprague de Camp, he produced a number of fantasies which were distinguished by wit, sophistication, a sense of humor, and a delightful and lively imagination—books such as the “Harold Shea” trilogy, com-1 prised of The Incomplete Enchanter (1941), The Castle oft Iron (1950), and Wall of Serpents (1960); and novels like Land of Unreason (1942), The Carnelian Cube (1948), an

On his own, Pratt lived to produce only two works of epic fantasy. Both are long, intelligent, carefully-worked-out novels laid in imaginary medieval worldscapes. Of these two, it is the first, The Well of the Unicorn (1948), that is the best known.

But the second of the two, and in certain ways the more thoughtfully conceived and brilliantly accomplished—The Blue Star—is almost completely unknown. It was never published in a magazine, unlike the majority of Pratt’s fantasy fiction. The one and only edition was published, along with two other novels Conjure Wife by Fritz Leiber and There Shall Be No Darkness by James Blish), by Twayne Publishers, Inc., in 1952 in a fat omnibus volume under the title of Witches Three, which had only one printing and has never been reissued. The book you are holding in your hands is the first and only paperback reprint of Pratt’s neglected work. After 17 years of obscurity, I am pleased to have been instrumental in getting this remarkable novel back into print again.

Pratt was a writer of unusual skill, who found more excitement in the interplay of ideas in action than in the familiar sort of swashbuckling; heroics. Sometimes his preoccupation with pure idea gets the better of him—the over-long and unnecessary Prologue to this book, wherein three men sit about drinking and talking over the philosophical concept of parallel worlds, and then share a mutual dream which is the novel itself, is a case in point: you can skip it and get straight to the story, if you like. But first and foremost, Pratt was a born story-teller in the grand tradition. The sort of man who read Norse sagas in the original, adored Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, and read collection of obscure national mythologies for pleasure. His invention never flags; his novel drives along at a rushing pace. As de Camp points out in an article on his late friend, “Pratt’s stories move right along. Something is always happening. His writing is full of novel conceits, flashes of wit, and interesting turns of phrase. The settings are lush and vivid.” Such a man was Fletcher Pratt. Such a book is The Blue Star. I commend both to you, with affection.

—Lin Carter

Editorial Consultant

The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Hollis, Long Island, New York

Prologue

Penfield twirled the stem of his port-glass between thumb and finger.

“I don’t agree,” he said. “It’s nothing but egocentric vanity to consider our form of life as unique among those on the millions of worlds that must exist.”

“How do you know they exist?” said Hodge.

“Observation,” said McCall. “The astronomers have proved that other stars beside our sun have planets.”

“You’re playing into his hands,” observed Penfield, the heavy eyebrows twitching as he cracked a nut. “The statistical approach is better. Why doesn’t this glass of port suddenly boil and spout all over the ceiling? You’ve never seen a glass of port behave that way, but the molecules that compose it are in constant motion, and any physicist will tell you that there’s no reason why they can’t all decide to move in the same direction at once. There’s only an overwhelming possibility that it won’t happen. To believe that we, on this earth, one of the planets of a minor star, are the only form of intelligent life, is like expecting the port to boil any moment”

“There are a good many possibilities for intelligent life, though,” said McCall. “Some Swede who wrote in German—I think his name was Lundmark—has looked into the list. He says, for instance, that a chlorine-silicon cycle would maintain life quite as well as the oxygen-carbon system this planet has, and there’s no particular reason why nature should favor one form more than the other. Oxygen is a very active element to be floating around free in such quantities as we have it.”

“All right,” said Hodge, “can’t it be that the cycle you mention is the normal one, and ours is the eccentricity?”

“Look here,” said Penfield, “what in the world is the point you’re making? Pass the port, and let’s review the bidding.” He leaned back in his chair and gazed toward the top of the room, where the carved coats of arms burned dully at the top of the dark panelling. “I don’t mean that everything here is reproduced exactly somewhere else in the universe, with three men named Hodge, McCall and Penfield sitting down to discuss sophomore philosophy after a sound dinner. The fact that we are here and under these circumstances is the sum of all the past history of—”

Hodge laughed. “I find the picture of us three as the crown of human history an arresting one,” he said.

“You’re confusing two different things. I didn’t say we were elegant creatures, or even desirable ones. But behind us there are certain circumstances, each one of which is as unlikely as the boiling port. For example, the occurrence of such persons as Beethoven, George Washington, and the man who invented the wheel. They are part of our background. On one of the other worlds that started approximately as ours did, they wouldn’t exist, and the world would be altered by that much.”

“It seems to me,” said McCall, “that once you accept the idea of worlds starting from approximately the same point—that is, another planet having the same size and chemical makeup, and about the same distance from its sun—”

“That’s what I find hard to accept,” said Hodge.

“Grant us our folly for a moment,” said McCall. “It leads to something more interesting than chasing our tails.” He snapped his lighter. “What I was saying is that if you grant approximately the same start, you’re going to arrive at approximately the same end, in spite of what Penfield thinks. We have evidence of that right on this earth. I mean what they call convergent evolution. When the reptiles were dominant, they produced vegetable-eaters and carnivores that fed on them. And among the early mammals there were animals that looked so much like cats and wolves that the only way to tell them apart is by the skeleton. Why couldn’t that apply to human evolution, too?”

“You mean,” said Penfield, “that Beethoven and George Washington would be inevitable?”

“Not that, exactly,” said McCall. “But some kind of musical inventor, and some sort of high-principled military and political leader. There might be differences.”

Hodge said: “Wait a minute. If we are the product of human history, so were Beethoven and Washington. All you’ve got is a determinism, with nothing really alterable, once the sun decided to cast off its planets.”

“The doctrine of free will—” began McCall.

“I know that one,” said Penfield. “But if you deny free will completely, you’ll end up with a universe in which every world like ours is identical—which is as absurd as Hodge’s picture of us is unique, and rather more repulsive.”

“Well, then,” said Hodge, “What kind of cosmology are you putting out? If you won’t have either of our pictures, give us yours.”

Penfield sipped port. “I can only suggest a sample,” he said. “Let’s suppose this world—or one very like it—with one of those improbable boiling-port accidents left out somewhere along the line. I mentioned the wheel a moment ago. What would life be like now if it hadn’t been invented?”

“Ask McCall,” said Hodge. “He’s the technician.”

“Not the wheel, no,” said McCall. “I can’t buy that. It’s too logical a product of the environment. Happens as soon as a primitive man perceives that a section of tree-trunk will roll. No. If you’re going to make a supposition, you’ll have to keep it clean, and think in terms of something that really might not have happened. For example, music. There are lots of peoples, right here, who never found the full chromatic scale, including the classical civilizations. But I suppose that’s not basic enough for you.”