Knee deep, p.1

Knee Deep, page 1

Contents

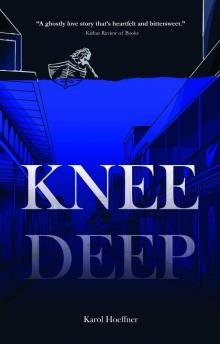

Knee Deep

Copyright © 2020 Karol Hoeffner. All rights reserved.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

Acknowledgments

Knee Deep

Karol Hoeffner

Fitzroy Books

Copyright © 2020 Karol Hoeffner. All rights reserved.

Published by Fitzroy Books

An imprint of

Regal House Publishing, LLC

Raleigh, NC 27612

All rights reserved

https://fitzroybooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN -13 (paperback): 9781646030095

ISBN -13 (hardcover): 9781646030507

ISBN -13 (epub): 9781646030361

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020930409

All efforts were made to determine the copyright holders and obtain their permissions in any circumstance where copyrighted material was used. The publisher apologizes if any errors were made during this process, or if any omissions occurred. If noted, please contact the publisher and all efforts will be made to incorporate permissions in future editions.

Interior and cover design by Lafayette & Greene

lafayetteandgreene.com

Cover images © by C. B. Royal

Regal House Publishing, LLC

https://regalhousepublishing.com

The following is a work of fiction created by the author. All names, individuals, characters, places, items, brands, events, etc. were either the product of the author or were used fictitiously. Any name, place, event, person, brand, or item, current or past, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Regal House Publishing.

Printed in the United States of America

1.

You know how people are always saying, “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas”? Well, what happens in New Orleans mainly gets ignored. The truly bizarre might end up as the punch line in a joke, but nobody gets their panties in a twist over comings and goings that ain’t any of their business. Let me explain what I mean. I once saw a little man, no more than three feet tall, dressed in a tuxedo chasing after a naked lady down Bourbon Street and nobody around me even blinked an eye.

I did not have a regular childhood.

I spent my formative years doing my homework bellied up to my daddy’s bar, a seedy-looking establishment in the shadow of Bourbon Street. And even though bartending is a highly respected occupation in New Orleans, I hated telling my friends what he did for a living, not because I was ashamed, but because that question was always followed by asking where he worked. You see, my issue wasn’t with his running a bar; it was the name of the bar itself that was the problem.

The Cock’s Comb.

Try explaining to teenage boys with nothing but sex and dirt on their mind, that cock’s comb refers to the fleshy red skin on top of a rooster’s head. It does not work; I was the butt of many jokes. And did I mention that I hate being teased?

Two summers ago, when I left an all-girls middle school for a co-ed Catholic high school, St. Bede the Venerable in the Ninth Ward, I begged Daddy to change the bar’s name to something less objectionable like Camille’s (my given name) Bar and Grill.

“Now, sweetie, you know I would do anything for you,” he’d told me, “but the Cock’s Comb has been in our family since my daddy’s daddy won it in a poker game from a gambler off the riverboat. These walls breathe history. Jean Lafitte sold his stolen goods in the back room. And Lee Harvey Oswald sat in that corner booth all by himself and ordered up a White Russian. The name of this bar and all it implies gives meaning to our lives. Sweetie, we are nothing without a sense of place.”

He was right about that. Where we live defines who we are. I spent so much time living in that bar, watching the clientele change as the sun moved across the sky. The afternoons were reserved for media types, journalists, and a few fiction writers who were replaced in early evening by what my mother called the “ne’er-do-wells” and what my daddy argued were “the true citizens of ’Orleans.” And late nights, the tattooed and pierced stumbled in. I grew up telling time by who pushed open the massive oak door and walked inside.

But none of us—not my parents, nor my cross-dressing tutor, nor either of my best friends—could have predicted the evil that would push through the doors of our lives following the tragedy of summer. Our story is a tale of survival, of those who lived and those who died. And although it is our story, I will begin with me because I am the one telling it.

***

All my life, I’ve been called a “Mardi Gras baby,” because, according to my daddy, I was conceived on Twelfth Night, which marks the day that the Three Kings came to Bethlehem to see the Baby Jesus. And as everyone within shouting distance of New Orleans knows, the Mardi Gras season of parades and parties begins with Twelfth Night and ends with the biggest street party of all on Fat Tuesday. Evidently, it was also the beginning of me.

I was conceived by parents who really weren’t ready to have a kid. It wasn’t that they were too young. My father, Donald Darveau, was almost forty and my mother, Mary Ellen Price, was a very mature twenty-five. They met right after she graduated from Southern Methodist University with a degree in economics. A job waited for her at a Houston investment firm but before she joined the rank and file of the executive class, she wanted one last fling in party city. So, she came to New Orleans for Jazz Fest.

The night before she met my dad, my mother stayed up all night drinking Long Island iced teas and listening to Dr. John sing “Gris-Gris Gumbo Ya, Tipitina.” The next morning, she made a mad dash across Jackson Square to join a Second Line parade coming out of the St. Louis Cathedral. Hung over and blurry-eyed, she ran into my father who, quite literally, knocked her off her feet.

He liked to say, “The day I met your mother was like finding a bird’s nest on the ground.”

Being a true Southern gentleman, he helped her up, brushed her off, and whisked her away to the Cock’s Comb so that she could recover. There, in the empty bar—all the regulars were at the Fair Grounds for Jazz Fest—he mixed up one of his famous Bloody Marys, poured it into a tall glass, served it alongside a basket of crab-stuffed Jalapeno hushpuppies, and asked her if she believed in love at first sight.

“I am not a romantic person,” Mary Ellen answered.

“I disagree,” he said. “Only a romantic person would follow a total stranger into an empty bar in the middle of the Quarter.”

“Or a fool,” she replied, taking her first sip of what she later called the best Bloody Mary in the history of the world.

“And you clearly are no fool,” my daddy said.

She took another long sip of her drink and listened to him describe the colorful history of his bar and the people who frequented it. “Many from the other side.”

“Other side of what?” Mary Ellen wondered and hazarded a guess. “Lake Pontchartrain?”

“No, I was referring to what lies beyond the life we know. New Orleans is peopled with souls tethered to the Crescent City and unable to move on to the sweet hereafter for one reason or another. Pirates, Voodoo Queens, Kings of Carnival—they all like to hang out at my bar,” he added with a wink.

My mother, who did not believe in ghosts or love at first sight, had the distinct impression they were not alone.

Like my daddy, I was convinced that there was a thin line between life and death. But where he counted ghostly visitations to his bar as evidence, I saw visions of the afterlife at sunset, on the horizon where sky meets water. Sometimes, even now, when I stand on the riverbank in the hazy glow between day and night, I feel the presence of others, as if I could actually reach out and touch the recently departed. Oh, but I’m getting way ahead of myself—again.

Back to the oft-repeated story of my conception. My parents had been seeing each other for some time when he invited her to a Twelfth Night party in the Garden District. After a couple of drinks, they slipped away unnoticed to a guest bedroom at the far end of the house. Back in the dining room, a gathering costumed crowd of harlequins, pirates, and jesters were admiring a glorious King’s cake sprinkled with granulated sugar tinted purple, green, and gold, the colors of Carnival. Baked inside the rich batter was a tiny ceramic baby doll and, according to tradition, whoever got the piece of cake with the baby in it had to throw the next party. Everyone in the room was having a gay old time, talking and laughing and drinking, when a six-foot-plus buccaneer eagerly accepted a slice of the cake, bit down on the tiny ceramic baby, broke her molar on its pointy little head, and screamed bloody murder.

Down the hall, my mother also screamed when my father explained what else had broken—his Deluxe Trojan condom. Those were, thankfully, the only two casualties of that Twelfth Night. But quite frankly, my mother would have preferred to have broken

Now it may seem strange to you that I know so much about my own conception, but the sad truth is my parents are always either having sex or talking about it, which I find equally annoying. And the sadder truth is that my parents did not need a baby to make their life complete. Now, I don’t want you to think that they don’t love me, because they do, but the simple fact of the matter is that all they have ever needed or wanted was each other.

My entire life I have felt like an extra bracelet on the arm of an overly accessorized drag queen.

And that is why my two best friends—Gina, pronounced with a long I as in va-gina, who lives in a mansion in the Garden District and acts slutty to offset her social pedigree; and Beano Benoit, the only gay quarterback on the varsity football team whose love for the game is equally matched by his talent for musical theater—believe that there is not a romantic bone in my body. They are convinced that the reason I have never had a serious boyfriend is because of the romantic drama I have had to endure in the form of my parents’ marriage.

But they are wrong. Terribly, terribly wrong. Every time I walk through the Quarter and look up at the shuttered windows and wrought-iron balconies, I feel the lusty emotions that linger from all who have lived there before. I hear love stories in the steamy jazz that floats out of bars and in the Second Line parades that jam narrow cobblestone streets. For heavens’ sake, the very first bus I rode when I was little was named Desire. That right there tells you something, explains how I grew up different, how the very act of living in New Orleans meant that romance was in my DNA, no matter what my best friends thought.

Of course, they had no idea that I was obsessing over someone, because I managed to keep the object of my own desire a secret from everybody, including and especially those two. I was pretty sure they would disapprove of my loving him, so I kept my silence. But in the middle of that hot, steamy summer and with August approaching, I was almost ready to say his name out loud.

2.

One thing for sure—if it’s August in New Orleans, it’s gonna be crazy hot. A week before my sixteenth birthday on one of those drippy, sweaty, so-muggy-you-can-barely-breathe kind of evenings, Beano, Gina, and I sat out on my front porch. We were swatting bugs with bible verse paper fans that Beano scored three weeks before at a church rummage sale in Lakeshore and sipping iced tea. Gina wanted to escape inside to air-conditioned comfort, but Beano could not be coaxed into the cool house; he lived for sweltering summer nights and acted like hot as hell was a gift from God.

“Humidity is sexy,” Beano argued.

A Tennessee Williams fan, Beano consciously fashioned himself after the Maggie character in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, who spent most of her time running around in her white satin slip, wiping the sweat off her chest and making lusty, sensual advances toward her pathetic husband.

Just so you know, that was Beano to a T.

“What are we gonna do about my birthday this year? It’s only a week away.”

“Why not do a Disney princess theme party, only make it nasty,” Beano suggested.

“Do not ruin Camille’s special day just because you have a secret desire to dress up like Arial in a padded seashell bra,” Gina said.

“Number one, a seashell bra does not require padding. And number two, if we’re doing the nasty princess thing, I’m in for Mulan,” Beano said.

“Of all the princesses, Mulan is the least likely to do the

nasty,” Gina said.

“True, but I would look fabulous in a kimono,” Beano shot back, posing theatrically.

Gina turned to me. “Seriously, Camille, you could invite a bunch of lame kids from school to your house for an even lamer dance-slash-barbecue, or we could go to the Quarter and have a real party because I know this guy who knows this guy.” Gina’s voice trailed off as she envisioned an evening of planned debauchery. When illegal substances were required, Gina always knew a guy who knew a guy who was only too happy to oblige.

Don’t get me wrong. I love the Quarter. But I had something else in mind. “I know it’s late notice and all, but can we do a party at your house?” I asked Gina.

Gina lived on St. Charles Street in the lush Garden District in a mansion built in a style Gina’s mother described as “a modified French château.” As impressed as I was with the house’s architectural pedigree and the fact that Gina had a four-room suite for a bedroom, what really wowed me was the backyard. The entire back of Gina’s house opened up to a formal French parterre garden, complete with ornate fountains and water works divided by beds of clipped boxwoods, herbs, and roses. At night, especially in the summer, Gina’s garden was possibly the most romantic place in all of New Orleans: the perfect setting for what I had in mind.

“What you people doin’ outside? Air-conditioning break or something?”

I looked up and saw my next-door neighbor, eighteen-year-old Antwone Despre, walking up the sidewalk with swag, home from his two-a-day football practice, helmet in hand. Reaching the front porch, he leaned against the Corinthian-style pillar, wiped the sweat from his brow, and asked Beano, “Why weren’t you at practice, bro?”

Beano’s voice dropped an octave. “Groin pull,” he said, punctuating his two-word excuse with a macho cough.

“Got any more of that tea?” Antwone asked, brightening the dusk with his languid smile.

“I’ll get you a glass,” Beano said, eager to avoid further conversation regarding ditching practice.

“Sweet tea’s on the first shelf in the fridge,” I hollered at Beano as he left to fetch it.

We always kept two kinds of tea in the house, sweetened and unsweetened. My mother, not being a true Southerner—people who say Texas is part of the South are just plain uninformed—preferred Lipton without sugar or lemon. But Antwone, like most of New Orleans, liked his tea sweet. I took a moment to admire him in the gathering darkness, hoping that the twilight would hide my deep appreciation. He was a light-skinned Black man with eyes as green as the reeds sprouting on the banks of the mighty Mississippi. And don’t get me started on his body, which could be compared to a Greek god, a real live Adonis. Well, you get the picture.

I have known Antwone all my life. He and his grandmother—whom everyone calls Bama, short for her given name Alabama Birmingham—lived next-door in a shotgun house identical to my own, only with the floor plan flipped. My bedroom was on the west side of the house; his bedroom on the east. Our houses were so close together we could listen in on each other’s lives.

I’ve looked up to Antwone since I was five, but I remember quite clearly the moment I fell in love with him. It was on a Wednesday in the late afternoon in March when I was fourteen. I was on my way home from basketball practice. Even though I was short and a girl, I played point guard on a boys’ team. (I have since given up the sport.) Eddie Deville, a smart-ass bench warmer, followed me home, screaming insults like “Ball-hog” and “Poser” and “Our fat forward’s got bigger tits than you.”

I knew that he was pissed because I was on the court and he was not, but after a while, his teasing began to wear me down. I made a sharp turn onto my street and sprinted toward my front porch, flying up the steps like I was going in for a layup. But as I reached the door, he called out the final insult. “Your momma must have slept with someone ’sides your daddy, ’cause you got hair like Ben Wallace.”

And that was when I burst into tears.

In case you don’t know, Ben Wallace was the most kick-ass small forward to ever play basketball, but he also had the worst hair in the entire history of the NBA, the wildest mess you have ever seen on or off a court.

My own hair has been a source of contention all my life. It’s impossibly thick, coarse, and wiry. My mother has straight-as-a-board, silky, fine hair and not a clue as to what to do with mine. She’s tried frying my scalp with chemicals; she’s burned my hair with the same iron she uses to press my daddy’s shirts. As a last resort, she finally grabbed me up on a Saturday morning and the two of us took the streetcar to a Black beauty shop downtown. It was there, at the Salon Baptiste on Chartres Street, I found my salvation.