The adventures of gerald.., p.1

The Adventures of Geraldine Woolkins, page 1

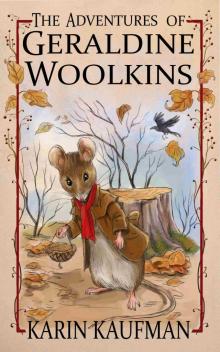

THE ADVENTURES OF GERALDINE WOOLKINS

KARIN KAUFMAN

Copyright 2015 by Karin Kaufman

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

This book is a work of fiction. The names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the writer’s imagination or have been used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to persons or mice, living or dead, actual events, locales, or organizations is entirely coincidental.

Cover and interior illustrations by Adrian Cerchez.

Contents

Map

Are You Ready?

WHISPERS OF WINTER

PAST HEDGES AND GROVES

FIRE LIKE A THOUSAND WOLVES

THE FLOWER SIPPER

THE WHITE RAIN

CHEDDAR BRUSH

THANKSGIVING AT THE HOLLOW

THE HOLLY BRANCH

WOLVES OF THE BARREN LAND

CHRISTMAS AT THE HOLLOW

A Note from the Author

The Geraldine Woolkins Series

Thank You!

Are You Ready?

Are you in bed, all snug and comfy under your blankets? Or are you on a couch or chair? Maybe you’re on a train or sitting in your back yard. You might be in school—or you might be waiting for a bus to take you there. It doesn’t matter where you are as long as you’re ready to read or listen to someone read to you, because books are an adventure like no other. Are you ready? Then you may begin.

WHISPERS OF WINTER

Geraldine Woolkins was sure the warm days of October would last forever. She had been born in April—the third of that month, to be exact—and knew nothing of cold, bitter days. Chilly nights, to be sure, but since first venturing from Mama and Papa’s house in the Hollow of their oak tree, all her days had been warm. And so Geraldine, wearing her new brown coat, played with more acorns than she gathered.

Papa had told her and her brother, Button, to roll the nuts, swiftly as they could, to the Hollow. There, he would take over, storing them in the winter pantry below ground. Instead, Geraldine and Button leapt atop the acorns, grasping their cups and rolling with them down the short hill that ran from the oak tree to No Wolves Creek.

“Geraldine! Button!”

Geraldine looked up. Even by the noisy waters of the creek she had heard her father. He was angry. No doubt his mouse whiskers were quivering like pine needles in the wind.

“Come up here, right now!”

Instantly Geraldine dashed up the hill, her brother a step behind her.

“Papa, I’m sorry,” she said as she reached the Hollow.

Papa said nothing. He looked down at Geraldine and Button, hands on his hips, his whiskers in motion. It was a fearsome thing to see Papa angry. He so seldom was.

“Nigel, they don’t understand,” Geraldine’s mama said as she emerged from behind the door to the Hollow, wiping her hands on a supple, new-fallen leaf. “Remember, you were a new mouse once. We both were.”

“That’s true, Lily,” Papa said. His whiskers stopped their twitching and his hands fell to his sides. “But all new mice need to understand. Would you bring me the Book of Tales?”

Mama smiled, dropped the leaf, and darted into the Hollow.

Geraldine knew this Book of Tales. Papa had read from it before, sometimes to himself in the sitting room, other times aloud, when the Woolkins mice gathered before the fireplace.

“The weather will not always be so generous,” Papa said as he took the book from Mama’s hands. “Sit down and listen.”

Geraldine and her brother sat, one on either side of Mama, watching as Papa laid the book before him and opened it wide, like the juiciest of walnuts.

Geraldine grinned. She couldn’t help herself. Most of the tales were meant to be lessons, for new mice, middle mice, and elder mice, but she loved to hear them. She loved the very sound of the stories’ words and the way she felt when Papa closed the book and all was well.

“This story is called ‘The Miracle of the Shrouded Pepper Plant,’” Papa said, nodding solemnly at Geraldine.

“You can read, Papa?” Button said.

Geraldine turned to her brother. Had he not seen Papa read before? Had he not paid attention?

“Of course I can read,” Papa said. “You’ve seen the books in our home.”

“Will I learn to read?” Geraldine asked Mama.

“In time,” Mama replied.

“But I want to learn now.”

Mama held a small finger to her lips.

“If we can begin,” Papa said, glancing from Geraldine to Button. “This is a true story.”

A tiny peep escaped Geraldine’s lips. True stories were the best stories.

Papa cleared his throat and began to read. “One October day in a land far away, three new mice, six months old and no more, left their parents to play in the cornfield outside their oak forest. Violet, Bean, and Tipple had promised to gather nuts”—Papa looked sternly at his children—“but it was such a fine, sunny day that they said to themselves, ‘Surely we have time before winter.’ They scurried up the brittle cornstalks, searching for nibbles of leftover corn, and ran through puddles in the fields. Their feet and tails became thoroughly wet, and when the wind picked up, they were cold.”

“Weren’t they wearing coats?” Geraldine asked.

“They were very foolish mice and left them at home,” Mama said. “Go on, Nigel.”

Papa cleared his throat again. “The sky turned dark, and the three mice became lost in the cornfield. The wind brought snow—a cold, white rain that covers everything it strikes and chills to the bone what it covers.”

Geraldine heard Button peep.

“They ran from the cornfields,” Papa continued, “but in the dark they lost their way and found themselves near a house. Not the welcoming home of elder mice, like the homes of their parents, but a large, bleak house that sat like a fat gray rock above the ground. The snow fell harder, and in the wind it blew sideways. Bean began to cry, and Tipple grew so cold that he could no longer walk. Violet took one of Tipple’s arms and Bean took the other, lifting and pulling and dragging their friend with all their might. They knew if they left Tipple behind, he would die.”

“Tipple,” Geraldine said, covering her eyes. “I don’t like not-happy endings.”

“We’re not at the ending yet,” Mama said. “Now open your eyes.”

Papa wet a finger on his tongue and turned a page in the book. “Now Violet saw nothing but white before her eyes,” he said. “Making her way forward, she reached out with one hand and touched something she had never touched before. She let go of Tipple and touched it again. It felt like a house, but not like a house. She fingered it, running her very cold hands down to where the white thing met the ground. It moved. She tugged and it lifted. There was no time to lose. The chance had to be taken.”

“What’s the white thing?” Button asked, trembling.

“Patience, children,” Mama scolded. “The story takes as long as it takes, and no less.”

Papa wearily rubbed his forehead. “This is why I like to read at night, when the children are in bed.”

“Patience, Nigel,” Mama said with a smile.

“Yes, dear.” Papa grinned back at her.

“I’ll try to be quiet,” Geraldine said.

“So . . .” Papa searched for his place in the book. “Violet held the white thing from the ground, just high enough for Bean, who was pulling Tipple by his legs, to slide under it. Violet followed, and the white thing dropped behind her. Inside it was dark as the darkest den beneath the earth, but now there was no snow and no wind, and the air above them smelled like a garden. Violet bent down to touch Tipple, to tell him it was a little warmer now, but he wasn’t moving. His hands were pulled in and stiffed. Curled and stiffed all at the same time. Now Violet cried. Where were they? What was this white thing? Why was it so cold, even beneath it? She heard Tipple make a tiny, soft sound and wrapped her arms around him, telling Bean to do the same. They must keep him warm.”

Geraldine stuck all of her fingers in her ears. This story would not have a happy ending. Why was Papa reading it?

“Stop that now,” Mama said, tugging on Geraldine’s arms. Button giggled and Papa silenced him with one look.

“While Violet and Bean were trying to keep Tipple warm,” Papa went on, “they heard a crunching sound, like foxes on brown leaves. It came nearer and nearer, and they held tight to each other, waiting. The white thing lifted, opening like the jaws of a wolf, and Violet and Bean pulled Tipple away from the opening and into the shadows. Then a great hand appeared—far larger than even the largest mouse and carrying something almost as large. It set that something on the ground. The white thing dropped, lifted again, and another something, held by two great hands, was set on the ground. And it happened again, until there were three somethings. To Bean, they looked like the very largest eggs he had ever seen.”

“Wolves,” Button whispered. “The somethings are wolves.”

“They’re not wolves,” Mama said. “Wolves are much bigger, and they live north of the Oak Forest.”

Papa sighed and s

“Tipple!” Geraldine shouted.

“In the morning, the sun shone through the white thing, and the air, which had cooled overnight, began to warm again. Tipple, who had fully recovered, giggled as he watched Bean climb his way up the plant they sat beneath. A pepper plant, Violet announced. Fresh and smelling like dessert, and kept from freezing overnight by a white shroud and three very hot stones. As Bean dug his teeth into one of the green fruits, Violet chided him. They would not return the generosity of Big Hands by eating his peppers. They were to leave now, mindful of the miracle of the shrouded pepper plant.”

Papa closed the book and gazed at Geraldine and Button, waiting, Geraldine thought, for one of them to speak. “That’s a good story,” she said. “A happy story. I like Big Hands.”

“If you see a creature like Big Hands, you must stay away from him,” Papa said sternly.

“But those creatures can’t be bad,” Geraldine said.

“I’m not saying they’re bad. But they’re big, and we know very little about them.”

“No,” Mama said, shaking her head. “Would a creature who so tenderly cared for a pepper plant hurt a mouse? Especially a new mouse?”

“But he ate the peppers, Lily.”

Button squeaked.

“Peppers are vegetables, Nigel. Don’t frighten the children.”

“Nevertheless . . .” Papa stood, cradling the book in his hands. “The lesson to be learned is this: There are whispers of winter—the time of snow—in the air. The snow comes quickly and without warning. And when it comes, it’s too late to gather food. Gather now, while you can. And don’t wander far from home, even on the finest October day and even wearing your brand-new coats.”

“Yes, Papa,” Geraldine said. “Come on, Button,” she said, nudging her brother. “Let’s get the acorns.” She didn’t like to disobey her parents, but if disobedience caused Papa to read from the Book of Tales, it wasn’t an all-bad thing.

Button and Geraldine spent the next hour helping Papa with acorns, and they worked an hour after that gathering wild chives from Mushroom Grove and crab apples that had fallen to the ground but not yet been discovered by the squirrels who lived on Chestnut Hill. Papa was pleased with his children and sent them off to play. “But not far,” he warned.

“Not far at all,” Mama called after them.

Geraldine raced for the Maple Forest, to Where the Ice Gathers, which had been her favorite place all the hot summer long. Button trailed behind her, but Geraldine paid him no mind. She was Violet. Brave Violet on an adventure.

She flitted over orange and red leaves on the forest floor, now and then stopping to sniff the air, so fragrant it was with lichens and molds and fallen maple seeds encased in their papery wings.

When she climbed partway up a tree trunk and clung to its shaggy bark, her eyes skyward on the treetops and the bright blue sky, she heard a familiar sound, like her brother Button’s peep but longer and louder.

“Penelope?” Geraldine said. She heard the sound again and searched the branches above her. There. It danced along a branch. It swooped, its wings, smaller than a maple leaf, nearly brushing Geraldine’s whiskers. “Penelope!”

“Geraldine!” Penelope rose and swooped again, coming to rest alongside Geraldine, clinging to the tree bark like a woodpecker, though she was no more than a house sparrow.

How Geraldine envied her friend. Born in June, Penelope had already traveled far and wide, even to Where the Bears Live. She had seen things Geraldine could only dream about—or hear about in the Book of Tales. Geraldine was stuck among the leaves and mossy things. Penelope floated wherever her heart took fancy.

“It’s me, it’s Button,” Geraldine’s brother said. He hopped up and down on an old log, waving his arms and flicking his tail.

“Follow me, you two,” Penelope said.

“It’s getting cold,” Button said. “We can’t go far.”

“It’s not far,” Penelope said.

Geraldine understood that far for a new sparrow and far for a new mouse were two very different things, but she was eager to follow Penelope.

“Follow me and see what I’ve found.” At that Penelope lifted her wings and flew to the next tree, and the next and the next, waiting at each for Geraldine and Button to catch up. In that way, Penelope, Geraldine, and Button came to the edge of the Maple Forest, to a hill overlooking a fat brown rock.

Penelope dove and landed with exquisite lightness on the ground next to Geraldine and Button. “I found a Big Hands creature,” she whispered.

Button peeped loudly, quickly covering his mouth to keep from doing it again.

“Big Hands,” Geraldine repeated. She felt her heart beat faster in her chest. “It’s really true—such creatures exist.”

“He has seeds and berries,” Penelope said, “and bigger things that taste like greenness and gardens.”

“Peppers,” Button said softly.

“And look,” Penelope said, waving a wing at the rock, “you can go right into his house. It’s not a rock at all. My mother says it’s called glass.”

“Glass,” Geraldine repeated. True, this rock seemed different from the rock in the story. It was brown, and in the middle, where there should have been more brown, there was nothing but light and shadows. But the shadows—she had never seen anything like them—troubled her.

“I’m going to explore,” Penelope said. “Watch me.”

“I want to explore too,” Geraldine said. If Penelope was going to explore, so would she.

“You can’t,” Penelope insisted. “It’s not safe for a mouse. Watch me, and I’ll come back and tell you what I saw.”

Penelope flew toward Big Hands’ house, flying high above it, circling and tumbling, joyful with the freedom of the air. There were no trees here to stop her, not like in the Maple Forest. Geraldine watched from the safety of the forest’s edge, envious once more, wanting more than anything to fly, to feel like a sparrow just once. She stretched out her hands and tilted her chin upward. She closed her eyes and felt the breeze on her face, her fur now feathers ruffled by the wind. “Flying,” she said.

A sound, something like an acorn falling from the beak of a bird to the rocks in No Wolves Creek, was followed quickly by the loudest squeak she had ever heard from Button. Geraldine opened her eyes. “What is it now?” she asked.

Her brother was staring at the rock, his mouth and eyes wide. “Penelope,” he said. “The glass hurt her.”

Geraldine looked to the rock, and there, just below the middle part where shadows and light played, was Penelope, motionless on the flat, gray ground, her wings drawn in, her delicate legs curled. All curled and stiffed.

“Penelope!” Geraldine cried. She darted toward the rock, Button far behind her, calling after her to stop.

Something in the middle of the rock moved, heaving outward like the gaping mouth of a wolf. Was it a door? It was far larger than the door to her home in the Hollow. Geraldine ducked into a still-green plant, hiding among its fleshy stems. Her breath came rapidly, and she felt her heart would burst. Mama and Papa would find her here, curled and stiffed on the ground.

She peered around a leaf, scanning the gray ground for Penelope, and saw the hands. Two of them. Thick claws reaching for Penelope, scooping her up.

Button scampered into the plant, hid behind his sister, and poked his nose above her shoulder, willing himself to look toward the rock. “Not Penelope,” he said.

Geraldine watched Big Hands lower Penelope into something white and as big as a hawk. It was a box, she thought. That’s what Mama had called it—though Mama’s boxes were much smaller. Bigger boxes held dead things, like very elder mice.