Summertime with geraldin.., p.1

Summertime with Geraldine Woolkins, page 1

SUMMERTIME WITH GERALDINE WOOLKINS

KARIN KAUFMAN

Copyright 2023 by Karin Kaufman

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

This book is a work of fiction. The names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the writer’s imagination or have been used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to persons or mice, living or dead, actual events, locales, or organizations is entirely coincidental.

Cover and interior illustrations by Adrian Cerchez.

Contents

Map

Are You Ready?

THE BAD MOOD DAY

GERALDINE AND THE LONELY SKY

THE CROW AND THE WOODPECKER

THE VERY PERILOUS ADVENTURE

BUTTON GETS LOST

THE SUMMER SNIFFLES

BACK TO SCHOOL

THE RUDE FOXES

GERALDINE FORGETS HER LESSON

WHISPERS OF AUTUMN

A Note from the Author

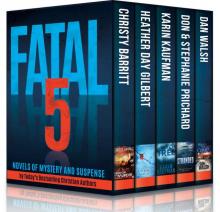

The Geraldine Woolkins Series

Thank You!

Are You Ready?

Are you in bed, all snug and comfy under your blankets? Or are you on a couch or chair? Maybe you’re on a train or sitting in your back yard. You might be in school—or you might be waiting for a bus to take you there. It doesn’t matter where you are as long as you’re ready to read or listen to someone read to you, because books are an adventure like no other. Are you ready? Then you may begin.

THE BAD MOOD DAY

Geraldine Woolkins woke to the sound of birds outside her bedroom window. A family of robins had built their nest near her family’s oak tree, and they were a noisy bunch, chattering away at all hours. Especially the early hours.

“Birds, be quiet,” Geraldine mumbled as she turned over in bed.

It was far too early. First the sun had woken her, and now the birds.

Worst of all, it was hot. How could it be hot when the sun still hadn’t climbed even halfway up in the sky?

She missed the cool mornings of May. She missed the fun of December and the silence of January, even though January was a time of scarce. She even missed June, which was warm and sunny but not too hot.

July was unpleasant.

“That’s the word,” she mumbled. “It’s unpleasant.”

She pushed her quilted blanket down to her knees and then kicked it to the end of the bed.

Just as she was drifting back to sleep, she was jolted awake as the front door to the Hollow slammed. That slam was followed by high-pitched whoops of happiness that traveled by her window and then faded into the distance.

Geraldine mumbled again. “Oh, Button, you’re as noisy as the birds.”

Her younger brother was an annoying mouse if ever there was one. He loved to rise early and run off to explore Acorn Hill, a land to the east of the Woolkins family home. “He acts like he’s never seen that place before,” Geraldine mumbled.

She decided she must stop mumbling.

She decided she must either go back to sleep or get up.

It was July, and so she had a perfect right to be agitated, but perhaps if she went to the kitchen, Mama would prepare a breakfast of strawberries for her.

The family’s fresh berries, along with dandelion leaves, rose petals, and carrots, were stored in the underground pantry, which remained chilly, even in summer.

“Fresh, chilly strawberries,” Geraldine mumbled.

Though she had decided to stop mumbling, following through on that decision was proving to be difficult.

The robins outside her window started up again, louder this time, as though they were quarreling with one another.

Geraldine sat up and swung her legs over the side of the bed. After a moment, she stood and got dressed, all the while reminding herself that it was hot and that her brother and the robins were annoying.

As if he could hear Geraldine’s thoughts, one robin grabbed hold of the bark outside her window, pecked at the glass, and cheeped loudly.

“My brother should live in your nest!” Geraldine snapped. “Then I could have peace and quiet in the morning.”

The bird flew off.

Geraldine made her way to the kitchen in her bare feet, enjoying the coolness of the floor. It was, in fact, the only coolness to be found in the Hollow. Yet she noticed that if she stood in one place for more than ten seconds, the coolness disappeared.

As Geraldine entered the kitchen, her mama, who was sitting at the table and chopping carrots, looked up.

Geraldine sat across from her. “Mama, can I have strawberries for breakfast?”

“We’re out of strawberries for now, dear.”

Geraldine couldn’t believe her ears. “But I’ve been thinking about them all morning!”

Mama smiled. “All morning? How long have you been up?”

“The robins woke me. Then Button.” On saying her brother’s name, a terrible thought occurred to her. Could it be? “Did Button have strawberries for breakfast?”

“He had the last one,” her mama replied.

“But why?”

“Should I have told him to leave it for you?”

Geraldine’s first thought was to say, Yes, you should have, but knowing better, and having been raised properly, she kept quiet.

“I believe there are two blackberries in the panty,” her mama said. “Wrap one in a dandelion leaf and take it with you when you go outside.”

Geraldine shook her head. “It’s hot out there. I want to eat in the kitchen.”

“It will get even hotter as the day goes on. Go now while you can.”

Geraldine, who wanted to stay exactly where she was, swiftly changed the subject. “Mama, do the robins annoy you and Papa?”

“Which robins, dear?”

Was her mama serious? Did she not hear those boisterous robins? “The ones that wake me every morning.”

“The robins in the tree next to ours? They sing such pretty songs!”

“Songs? Mama, they argue.”

“All God’s creatures argue now and then.”

“Not when the sun is just coming up.”

Mama laughed and chopped the last of her carrots. Then she swept the carrot pieces into her walnut-shell bowl. That done, she wiped her hands on her apron and fixed her eyes on Geraldine. “Enjoy the robins while you can, Geraldine. They’ll leave in the fall, and they won’t be back until next spring.”

“I miss springtime,” Geraldine grumbled.

“In the springtime you wanted summer.”

Mama was right. In the spring she had wanted summer, and now, in the summer, she wanted autumn. It was peculiar, and Geraldine really didn’t understand it. Her own feelings could be so puzzling. Whatever she didn’t have was what she wanted, and what she had was what she didn’t want.

“Aren’t you hot, Mama?”

“Of course I am. It’s July, the hottest month of the year.”

Mama went to the cabinet over the stove and brought down another walnut bowl.

“You’re not making hot soup, are you?” Geraldine asked.

“I’m making a salad.” Mama set the bowl on the table.

“That’s okay. I guess. You know what, Mama? Even my feet are hot.”

Geraldine examined a scratch in the table, running one of her fingers up and down it. She was stewing. That’s what Papa had called thinking grumpy thoughts over and over again until it hardly took any effort at all to think them. Your thoughts traveled easily to the places you took them time and time again, he said. They traveled like acorns rolling down a rut in a field—or a finger following a scratch in a table.

“I know what you can do, Geraldine.”

Geraldine looked up. Mama had a familiar expression on her face. One she planted there when she wanted others to cheer up and stop being grumpy, even if they had a right to be grumpy.

“Go to the shallow pond near the Maple Forest,” Mama said. “You can wade in and cool off. It’ll be fun. You might even get chilly!”

“Maybe.”

“Try it.”

“It’s too hot. I want to sit here for a while and try to get cool.”

Mama put her hands on her hips. “Go to the pantry, get a blackberry, wrap it in a dandelion leaf, and take it to the pond. This instant.”

It was no time to argue. Mama was growing agitated. Geraldine resolved to do as she was told, but as she rose from the table, she also resolved to keep stewing. No one could see what she was thinking, after all. Her stewing thoughts were private.

In the pantry, she grabbed the largest of two blackberries and wrapped it in the freshest dandelion leaf, and then, without a glance at her mama, she marched out the door and made her way to the shallow pond near the Maple Forest.

By the time Geraldine had reached the pond, her arms were tired from carrying the juicy berry. She regretted not taking the smaller of the two, and she stewed about that for a minute.

She sat on a flat rock in the shade of a maple tree and laid her breakfast in the grass at her feet. She would eat when she was good and ready, and not a moment before.

What would August be like? she wondered. She faintly remembered

“It’s always the same,” she said aloud.

At least she wasn’t mumbling.

She looked down at her dandelion-wrapped berry, half of it sticking in the sun and quickly losing its sweet coolness. “It’s hotter by the pond than at home,” she said, still speaking out loud.

She thought of wading in, as her mama had suggested. The water would cool her hot feet. But she knew the pond’s bottom would be slimy with mud—or worse. There might be algae down there, like she often saw on rocks.

What if she stepped on squishy bugs?

She lifted her head and searched the skies for her sparrow friend, Penelope Huckleberry, though she knew Penelope was visiting family far north of the Maple Forest, in a land called Where the Bears Live, and wouldn’t return until August.

Why couldn’t Penelope and her family live next to the Hollow, rather than those rude robins?

She longed for an adventure. If only she could fly and feel the air caress her like cool feathers. Was it possible to have an adventure on such a hot, sunny day, when she didn’t feel like moving?

“Why does it have to be so hot?” she said.

“Because it’s July, silly mouse,” a small voice replied.

Geraldine’s body went rigid while her eyes darted about the trees. She was alone by a hot pond on a hot day, which meant that something bad might happen. Yet the voice she’d heard was small—not the voice of a wolf or a fox.

Trembling, she called out, “Where are you?”

“Over here.”

“Where?”

“You’re not looking in the right place, silly mouse.”

“Then tell me where to look, and don’t call me silly.”

“Look down.”

Geraldine looked down.

“Now look to your left, but just a little.”

Geraldine gasped. To her left, the length of a maple leaf away, a brown beetle sat in the grass. She had thought it was a broken-off bit of a dead leaf, not a living creature.

“Now you’ve got it,” the beetle said, waving its front legs in greeting. “My name is Drake. What’s yours?”

“Geraldine. You’re very small, Drake.”

“And you’re very large, Geraldine. Though not as large as a rabbit.”

“What are you doing there in the grass?”

“What are you doing there on the rock?”

“I’m feeling hot. I’m almost sweating, and I don’t think mice sweat.”

“July is a hot month, silly mouse.”

“Everyone keeps telling me that.”

“Is that because they think you’re too silly to remember?”

Geraldine puffed out her cheeks and looked away. What a rude bug. What a terrible day.

“Hello?” Drake said. “Did we stop talking already? But we only just started.”

Now Geraldine turned her whole body away from Drake. She was in no mood for a contentious conversation with a rude beetle.

“Can I have the blackberry inside that dandelion leaf?” he asked.

Geraldine spun around. “Don’t you touch it. It’s mine.” She hopped off the rock, ready to defend her breakfast if need be. “How do you know it’s a blackberry?”

“I can smell it, even wrapped in a dandelion leaf. Summer berries are deliciously tasty. If it’s yours, why don’t you eat it?”

“I’m saving it for later.”

“No you’re not. I’ve been watching you. You don’t even care about it.”

“It doesn’t matter. It’s still mine, and it’s too big for you. It’s bigger than your whole body.”

“I’ll have you know I could finish that berry in an hour. Let’s bet on it.” Drake stuck out a long, spindly hand so they could shake on the deal.

But Geraldine knew what Drake was up to. Even if he lost the bet, he would win, for his stomach would be full to bursting with blackberry, and she would be left with nothing more than a nibbled stub.

“If you can’t eat it all and you lose our bet, what do I win?” she asked.

“Oh.” Drake thoughtfully rubbed his chin. “I hadn’t considered that. I’m so hungry it slipped my mind.”

“Eat some grass if you’re hungry. And leave me alone.”

Geraldine stepped between Drake and her blackberry, making it clear that he was to have none of it.

“I only wanted a little,” he said. “Please?”

“You want to eat the whole thing. You told me so. Now go away. This instant.”

Drake turned and began to walk away from Geraldine, and it was then she saw that one of his legs, at the very back of his body, was missing. As he moved over the grass, he wobbled slowly side to side, and Geraldine couldn’t help but think that a raven would find him a tasty—and very easy to catch—treat.

The beetle couldn’t run, and there were few places around the pond to hide. The fallen maple leaves in the forest would provide shelter, but as she watched Drake, she knew it would take him all day to reach the forest. For her, it was ten seconds away.

“Drake, wait.”

The beetle stopped. He wiggled his body around until he was facing Geraldine. “Why should I wait? You’re the most unpleasant creature I’ve ever come across.”

Geraldine couldn’t believe her ears. “I’m nothing of the sort! I’m a very pleasant mouse. You interrupted me. You interrupted my . . . my private stewing, and you tried to steal my blackberry.”

Drake shook his head. “Why can’t you share just a little of what you don’t even want? I can’t climb blackberry bushes anymore. Or raspberry. I haven’t had fruit in a very long time.”

Regretting her ungracious behavior, Geraldine plopped down in the grass and tried to plant a kinder expression on her face. “What happened to your leg?”

Drake looked over his shoulder, back to where his leg used to be. “I was playing and I caught it under a rock. After a while I squirmed and pulled to get free and it broke off.”

“That must have hurt.”

“It did a little, but it doesn’t now. Though climbing and walking are hard.”

“Can’t your family share their fruit with you?”

“They don’t know where I am. I lost them when my leg got caught. They called and called and I couldn’t come. I’m pretty sure they think I ran away.”

Geraldine sat straight as a river reed. “That’s terrible! When did this happen?”

Drake hung his head. “Three days ago. I was under the rock you were sitting on.”

“And you’ve been by that rock all this time?”

“Yes, Geraldine. I always stay near it, in case the ravens come. My family lives in the Maple Forest. I know the tree where they live, but it’s far away, and the ravens will get me if I try to walk there.”

Geraldine leaned backward, twisted a little, and seized hold of her breakfast. She rolled it forward and stopped it half an inch from Drake. Then she unwrapped the blackberry and told Drake to eat just as much as he wanted. “You can have the dandelion leaf too, if you want.”

Drake smiled. He leaned toward the berry but didn’t eat it. “What will you eat, Geraldine?”

“I can eat plenty of other things later. You eat the blackberry.”

Seeing the berry unwrapped on the grass before her, the sun glinting off its purple-black skin, she was suddenly hungry. But there would be more berries at home in a few days, and in the meantime there were leaves and roots and leftover sunflower seeds from the pantry.

And Mama was making soup for lunch. Or dinner. It didn’t matter which, for Mama always made good soup.

Drake hobbled forward and sniffed the blackberry. “Are you sure? It’s all mine?”

“All of it. I don’t care.”

He took a tiny bite, and the look on his face—and the juice dripping from his chin—told Geraldine that the berry was quite delicious.

Then Drake took another bite, and another, and in no time he had finished more than half the berry and his belly was puffing out like Geraldine’s belly sometimes did after a particularly large piece of her mama’s pumpkin pie.

He settled happily into the grass, and his face wore such a big smile that Geraldine almost laughed. Indeed, she would have laughed if she hadn’t stopped herself and remembered how miserable she was and what a terrible, hot day it was.