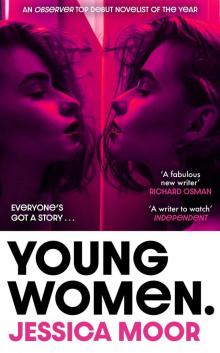

Young women, p.1

Young Women, page 1

For Jason, who wanted to know what happened next.

Dedicated to the memory of John and Audrey Cunningham.

Half victims, half accomplices, like everyone else.

Jean-Paul Sartre, Dirty Hands, used by Simone de Beauvoir

as epigraph for The Second Sex

Contents

Prologue

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Part Two

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Reading Group Questions

Copyright

Prologue

I WATCHED HER FILM last night. Moitié Victime, it was called.

She was sixteen in that movie. You could tell by the way that the director shot the sex scene that he knew that too. Maybe not emotionally, but contractually.

I hunched my body around the laptop, my nose inches from the screen. To see her better. To reach through and grab her.

Her face was perfect for period pieces. She made sense with her hair (chestnut brown here) back in a chignon, Cupid’s bow mouth accentuated in creamy red lipstick. Perfect for an ingénue in Vichy France, a double agent. That was her role in this film, and that was always her gift, her magic. The way she worked in every context, not just plausible but perfectly suited. Inevitable.

She looks so young in that film. Deer-limbed and emeraldeyed, afraid in that way that men find sexy. So different to how she was when I knew her. I watched the film once as a forensic exercise, ignoring the parts of it that weren’t her, or were at least an echo of her.

After I saw her in the footage of the protest, I watched her film a second time. This time I put on my dressing gown, poured a glass of red wine, let myself stretch out over the sofa. I watched for the colour palette and the shot composition and the languid, reproachful pan of the camera over the cafes of a small-town square where the Nazi officers sat.

I treated it as an aesthetic experience. It worked well that way.

Part One

Chapter One

THE FIRST TIME I saw Tamsin her eyes were closed. Her lashes didn’t flicker, even as the sirens wailed closer, even when they were so close that we could feel their screams through our bodies. Even as our skulls jolted with the knock on the tarmac of police boots.

The whole time her face was serene, as if she were dead and laid to rest.

I turned my head to look at her, feeling the road’s grit scrape against my scalp. Her hair was gold. What they call old gold – the colour of gilded furniture, with just the slightest tinge of olive. Skin strobed by the lights of Piccadilly Circus. In all the shouts and slams and the crashes and the cries, she stayed lying there, unmoving. She seemed, in that moment, other-worldly.

As the police drew level with us we were engulfed by noise. It was then that her eyes popped open. They were green and feline, yellow-flecked.

I must have looked afraid. She looked at me. Grabbed my hand. Then she was yanked upright and her fingers were torn from mine. She went limp, resisting arrest as a corpse resists its own concealment.

Cop’s breath on my neck, arms pulled painfully behind me, they half dragged, half carried us away. I couldn’t stop my feet from skittering along in obedience. Tamsin was smiling slightly, as if she thought the whole thing was just a little bit funny.

They put us all into the van and slammed the door shut, harder than I thought they would, as if they were making sure we got the full experience. It was all people like me – young, white, privileged enough to be dizzy with excitement at the thought that they’d actually been arrested. Some were looking around, smirking, heaving in their breath. Others sat there, performatively grim. The flush-cheeked girl beside me on the bench was furiously tweeting.

Tamsin was sitting opposite me. Again, her eyes were closed. She seemed so calm, so sure that the right thing to do was disappear into herself, like her mind was a fortress.

I settled for a little half-smile, as if I’d been here before, as if I knew the drill. I made sure to look around at the other faces in turn, so that nobody would notice that all I really wanted to do was to stare at her.

I lost sight of her for a bit, while we were all being processed at the station. Someone started singing and everyone joined in. First ‘Amazing Grace’, then ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’. I didn’t know most of the words so I just mouthed along and joined in with the chorus. Then nobody seemed to be able to work out what to sing next; someone shouted, ‘Anyway, here’s “Wonderwall”.’ We laughed like we thought it was stupid, but still we sang along. Everyone knew all those words. Then ‘Rehab’ by Amy Winehouse. It didn’t really make sense, but it felt like it meant something when everyone started stamping their feet on the concrete floor and singing no, no, no.

We didn’t find each other again until the singing had died away and everyone was sitting or lying on the floor. I was cross-legged, trying to sit with my spine straight, the way my teacher did in yoga. My hips hurt and my back ached. The adrenaline spike had left me feeling lifeless.

Tamsin touched my arm lightly and said, ‘How are you doing now, sweetie?’ As if we were just carrying on from an earlier conversation.

Her accent wasn’t English. At first it sounded American, but as we talked, I started to wonder if it wasn’t that international inflection that you hear when people speak English like it’s their native tongue, but have no place to tie it to.

‘I’m doing better,’ I said.

‘You looked scared when I saw you. I hope you don’t mind I held your hand. I do stuff like that without thinking it through. You English don’t like being touched.’

‘I didn’t mind.’

I didn’t mind, either, when she pulled out a worn little deck of cards from her pocket and asked if I wanted to play. I didn’t give my standard response – I didn’t like card games, too much organised fun – I just nodded. We sat cross-legged on the floor opposite each other. She bent forward from the hips the way babies do, joints fluid, hair slipping from her shoulders and forming a curtain to encompass the two of us. I couldn’t work out how old she was – she could have been anything from sixteen to thirty – whether the easy way she was talking to me was a sign of naïveté or maturity.

I asked her what had brought her to the protest today.

‘If we don’t do something about climate change, it seems to me like there’s no point in caring about anything else,’ she said.

I nodded, and said that it was something similar for me. That morning I’d set off to the protests with my flatmate and some of her friends, all of us sitting on the Overground with our arms around our placards like they were something we loved.

They let us go sometime after midnight. They processed Tamsin first, and she didn’t say goodbye before she left. I assumed that was that – one of those brief intimacies, like from a plane or in a queue, that never got its chance to take root. I emerged from the holding area with Hana, my flatmate, and a couple of her friends. But when I got to the waiting area of the police station there she was, sitting on one of the plastic chairs among a gaggle of people staring listlessly at their phones. One Doc Marten-clad foot resting on her knee, the way a man crosses his legs. She was reading a paperback book.

Tamsin looked up expectantly when I entered, as if she’d recognised my tread, and smiled.

‘Drink?’

None of the bars were open. Hana and the rest of her gang quickly begged off, and it would have been obvious for me to get the last train home with them. But instead Tamsin and I found an all-night Tesco Metro. Everyone looked dull under that awful strip lighting, but not Tamsin. Her skin seemed to carry with it a patina that couldn’t be scrubbed away by too much reality.

I instinctively reached for the bottle of Pinot Grigio that was on offer, but she waved her hand at me and said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll get this.’

She was scanning the top rack of the bottles of red wine.

‘That one’s on offer.’ I pointed.

She shook her head. ‘They’re bullshitting you with these offer things, ignore them.’

She chose a bottle of Malbec, then went over to the refrigerated section and selected two different kinds of cheese. She cradled them in the crook of her arm like they were kittens, her hand clasped around the neck of the bottle.

‘Okay, we just need . . .’

She walked quickly, on the balls of her feet, to the baked goods section and felt the baguettes in turn, through their cellophane wrappers.

‘These are fresh,’ she announced, and her face seemed to brighten, as if it was the best news anyone could have given her.

All the self-checkouts were available

‘How’s your night going?’ she asked the cashier, a tall, loose-limbed boy of seventeen or so, who looked like he was still waiting to grow into his own frame.

I expected him to grunt something in reply. I expected to find that she didn’t really understand how London worked, how people were here. But he shrugged and said, ‘Yeah, not too bad. We’ve had a lot of people in from the protest today.’

‘That’s where we’ve just come from.’ She gestured at me, and it occurred to me that, as far as this cashier was concerned, we could be old friends. ‘What did you make of it all?’

‘Well, it took me a long time to get in to work.’ I expected him to leave it at that, for him to brusquely twist the card holder towards her and disappear back into his role. ‘But you know, I support it. I’d be out there too, if I could. It’s important. I read this thing online this morning and it said “there’s no Planet B”.’ He laughed. ‘I know it’s cheesy, but it stuck with me. No Planet B. Someone’s got to do something.’

I’d been planning to dart forward, to tap my card on the reader, to beat her to it. But that would have felt like interrupting, so I held off until it was too late. It cost £21.89, the wine and the cheese and the baguette. She didn’t even look at the reader.

The summer night was still warm. None of the parks were open. Tamsin wanted to climb over the railings into Victoria Embankment Gardens on the river. I didn’t. It wasn’t that I was scared – it just felt too raw an exercise of privilege for us to trespass, knowing that if we were caught there would be no real repercussions. I said something along those lines to her.

She gave me a measured look. ‘Who is it that you think that’s helping?’

I didn’t have an answer, so I climbed too. For a moment I felt weightless.

She somehow managed to fashion a cheeseboard out of the cardboard packaging. She poured half of the Malbec into her emptied-out steel water bottle and gave the rest to me. We clinked the two together.

‘Was that your first arrest?’

‘God, yeah. I’m such a rule-abiding little creep.’

‘To many more, then!’ She raised her bottle as if saluting not just me but the Thames, the reflection of the London Eye in its inky surface, the darting lights of the bridges as they lunged across the river. She seemed happy for the silence to remain untouched, and there was something in the quality of it that I liked too. Yet there were some obvious questions that still needed asking.

‘So, you’re from America?’

‘Montréal,’ she said, pronouncing it the French way. ‘Canada. Originally. I moved to the States when I was twelve though, so you’re kind of right. Connecticut. Fucking kill me.’

‘Sorry. I didn’t mean to assume.’

‘Don’t worry. Canadians are too polite to care when we get mistaken for Americans.’

‘Montreal’s in Quebec, right?’ I couldn’t have sworn to it then – it was a guess from the way she said the name.

‘Right.’

‘So you speak French?’

‘Bien sûr.’ She pronounced the words strangely, as if the vowels were dangling from her mouth. ‘French and English from living in Quebec. Then my mom’s Italian and my dad’s Polish.’

‘Like, first generation?’

‘Right. Not that weird thing of saying you’re Irish when no one in your family’s set foot in Ireland for more than a century.’

‘So you speak Polish and Italian too.’

‘Sure.’

‘Wow.’

‘There’s a lot going on there.’ She took a sip of wine from her water bottle and slid down the bench so that her head was resting on the back. Staring up at the stars.

‘Is Tamsin an Italian name? Or Polish? It sounds . . .’ I cast about, unsure.

‘It’s one of those strange bastardised names. A short form that turned into a name all by itself. It’s a contraction of Thomasina. That means twin.’

‘Do you like your name?’ A playground question.

‘I’ve always thought it was kind of ugly. Yours is so much prettier.’ Said without any smile to indicate flattery.

I didn’t agree. I didn’t really think Tamsin was a pretty name either. Rather, it sounded like the name of someone who didn’t care if her name was pretty.

‘Emily means industrious. Striving.’ I sighed. ‘There were seven different Emilys in my year at school.’ I could still count the fleet of Emilys off in my head, ten years later. Morris, Chapman, Kim, Parker-Johns, Sullivan, Cheung.

And me.

‘And are you?’

‘Am I what?’

‘Industrious.’

I took a sip of the wine. ‘I mean, sure.’

‘That’s why you were at the protest. You care.’

‘Everyone cares.’

‘But not everyone gives up their weekend.’

I stayed quiet.

‘Anyway, industrious or not, that doesn’t mean it’s not a pretty name. It’s so classic. So English. Emily.’

She said it in an English accent – not the cod-aristocraticslash-Cockney that I’ve heard Americans do, but an impressive approximation of RP, cut-glass and perfect, like Helena Bonham Carter in A Room With A View.

‘But anyway . . .’ She looked at me, popping a crumb of Stilton into her mouth. ‘My god, the cheese in this country is so fucking good. I still can’t get over it. Anyway. Where are you from?’

‘Here,’ I said, gesturing to the bench. ‘I mean, London.’

‘Amazing.’

‘Not really. I’m not from a cool part. I’m from Wimbledon.’

I waited for her to say ‘Like the tennis’, as if that settled everything, but she didn’t. Instead she said, ‘So what’s that like? Posh? Gritty?’ She articulated the two ts carefully, as if she was enunciating them one at a time. ‘Diverse?’

‘In a sense. I mean, Wimbledon itself is quite posh.’

‘I’m sensing a but. Are you posh? I find it hard to tell.’

‘I’m . . .’ I thought about the red-trousered croquet-playing specimens I’d met at university. ‘I’m sort of medium. Not posh exactly . . . my ex was really posh.’ Harry had always made it clear how gauche I was, that I’d never done a good enough job of imitating people like him. My exact social class without him was another thing that I had yet to work out. ‘I went to a grammar school.’

‘Is that like private school?’

‘No.’ Explaining myself from first principles. It was liberating to not feel stuck in the usual class shorthand. ‘State school. But they did this high-pressure entrance exam, so the mood of the school is completely neurotic. All-girls.’

‘My god.’ She laughed. ‘I don’t want to be mean about it or anything.’ The way she said ‘about’ reminded me that she was part-Canadian. A-boat. ‘It’s just a strange concept to most North Americans, a single-sex school. Unless you’re Catholic or something. Which I actually am, and I still didn’t . . . Anyway, go on.’

‘So yeah . . . crazy school.’

‘Crazy in what way? Is that where you learned to be a “rule-abiding little creep”?’

She repeated my words back to me in another British accent, her imitation too good a mirror to feel like mockery.

I paused. Took a sip of wine.

I didn’t want to give her my spiel, the same little speech about my adolescence that I’d developed on my gap year and perfected during my first week at university. As a lawyer I was prone to the spiel, the shorthand, the potted summary. But mature people didn’t talk like that.

I shook my head. ‘Anyway, that’s all so boring.’

‘It’s not boring to me. Did all that stuff affect you? I mean, I guess it must have, in that atmosphere. But did it . . .’

‘. . . I’d say I got off pretty lightly. I wasn’t exactly down the mines.’

‘Sure.’

‘Tell me about Montreal.’

I guess I was expecting a breakdown of the city’s demographics. Or a quick sound bite on the politics, a survey of rent prices.

Instead, Tamsin told me about a city built on a mountain, a mountain that rose out of the vast icy river that ran all the way from Lake Ontario to the North Atlantic. I couldn’t think exactly where those places were; it seemed enough to embrace the sounds of the names. She told me that sometimes, in the winter, you saw seals in the river. She said the mountain was turned into a park where people hung out and played guitar in the summer. That there was a great cross on top of that mountain that you could see from all over the city. She told me about the network of tunnels that ran underneath the city so that in the winter people could get to work, to the shops, to university, when the temperature dropped so low that you couldn’t go outside.