The duchess, p.1

The Duchess, page 1

Copyright

Published in 2021 by Welbeck Fiction Limited,

part of Welbeck Publishing Group

20 Mortimer Street London W1T 3JW

Copyright © Murgatroyd Limited 2021

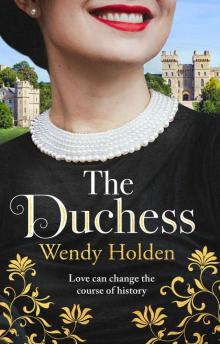

Cover design by Alexandra Allden

Cover photographs © Matilda Delves / Arcangel (woman);

Ian Dagnall / Alamy (Windsor castle); Shutterstock.com

The moral right of Wendy Holden to be identified as the author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners and the publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book: 978-1-78739-626-5

Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Dedication

To Noj, Andrew and Isabella

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue: The Duke of Windsor’s funeral, June 1972

Chapter One: Honeymoon in Paris, 1928

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: Driving from the airport, June 1972

Chapter Four: The new Mrs Simpson, Upper Berkeley Street, London W1, 1928

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: London, June 1972

Chapter Eight: Embarking for America, 1929

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: Buckingham Palace, June 1972

Chapter Eleven: Bryanston Court, London W1

Chapter Twelve

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: Buckingham Palace, June 1972

Chapter Thirteen: Bryanston Court, London W1

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: Buckingham Palace, June 1972

Chapter Sixteen: Fort Belvedere, Windsor

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: Windsor Castle, June 1972

Chapter Seventeen: Fort Belvedere, Windsor

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: Buckingham Palace, June 1972

Chapter Twenty-One: Bryanston Court, London W1

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: Windsor Castle, June 1972

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Chelsea, London SW3

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, June 1972

Chapter Thirty-Nine: London, 1935

Chapter Forty

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, June 1972

Chapter Forty-One: St James’s Palace, London, 1936

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

The Duke of Windsor’s Funeral: Royal Burial Ground, Frogmore, Windsor, June 1972

Paris: June 1972

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Prologue

The Duke of Windsor’s funeral, June 1972

In his coffin of English oak, on the Royal Air Force plane, he had gone before her. She had not wanted him to be alone on that last journey. But grief had weakened her and her doctor insisted she stay in Paris. A few days later a plane of the Queen’s Flight arrived to bring her to England for the funeral. Now they were almost here. Below, London spread flat and grey. There was the squiggle of the Thames, there the Tower, Tower Bridge, St Paul’s.

Wallis stared at her reflection in the cabin window. She had never felt old before. He had made her feel youthful and beautiful always. But with him gone, she was suddenly a woman in her late seventies.

Her once-smooth, pale skin was furrowed and powdered. Behind her brave red lipstick her mouth was wrinkled. Hair that had been naturally black and glossy was now dyed and lacquered. Only her navy-blue eyes were the same. Framed thickly with mascara, they registered shock and bewilderment.

She still could not believe it. It was a dream from which she would soon wake, in her bedroom at home in the Bois de Boulogne. Bwah de Bolone, as he always drawlingly pronounced it.

Opposite, her companion shifted in her armchair. ‘The Queen’s Flight might be the most prestigious in the world,’ she remarked, ‘but no one could claim its aircraft are the most luxurious.’

Wallis gave Grace a weary smile. She knew her old friend was only acting the spoilt part, trying to distract her from the trials that lay ahead. How would she bear a single moment of any of it? And yet borne it must be.

‘I suppose her Purple Passage has proved useful,’ Grace conceded, referring to the invisible red carpet in the sky that only the Queen’s Flight could use.

‘It’s called Purple Air Space,’ Wallis corrected. ‘As well you know!’

Grace had been Princess Radziwill in a former marriage – Jacqueline Kennedy’s sister Lee was the current one. Grace, meanwhile, had moved on to become the reigning Countess of Dudley. She and Wallis went back years; besides a dry sense of humour they shared a similar taste in clothes and an outsider’s perspective on the British upper class. Both were foreigners – Grace from Dubrovnik – and neither had been born aristocrats.

‘I’m grateful to Lilibet anyway,’ Wallis went on. ‘She’s been very kind. She came to see us, which was good of her.’

After decades of cold war with the Windsors, the call had come out of the blue. The Foreign Office relayed that the queen wished to visit her uncle at his Paris home. She would come during her five-day state visit to France.

Lilibet had clearly heard about the ex-king’s cancer. Someone had said that after the failed radiation treatment his life hung by a thread. She wanted to say goodbye, but only afterwards had the high-stakes game that was the run-up to the visit been revealed. Britain’s ambassador in Paris had been adamantly against the idea. It would, he had warned, spell disaster for Anglo-French relations if the ex-monarch died before the present one left England. The state visit would have to be cancelled and President de Pompidou would be greatly offended.

The farcical aspect this lent the situation would, in other circumstances, have amused the former Edward VIII. But he rose to the occasion. His country needed him. He was important in a way he hadn’t been these past thirty-six years. Through sheer strength of will he hung on and waited during the whole of the royal visit. Lilibet did not hurry, dazzling banquets at Versailles and the British Embassy in one tiara after another before touring Provence and attending the races. Finally, accompanied by Princes Philip and Charles, she arrived at rue du Champ d’Entraînement on a sunny May afternoon.

Grateful as she was to her niece-in-law, Wallis could not help being struck by the hideousness of the royal-blue hat and the horrible matching box-pleated suit. Amid the riot of pattern, Lilibet’s bow-shaped diamond brooch and three strings of perfect pearls were completely lost. How could such a naturally pretty woman with such wonderful skin contrive to seem so plain?

In his overcoat Philip had looked like a testy bank manager while Charles, his striped shirt clashing with his floral tie, had just looked uncomfortable. Beneath his checked tweed jacket, his shoulders sloped. His eyebrows too; his face wore a permanent expression of weary disappointment.

Wallis had felt sorry for him. She knew what it was to be steamrollered by the Windsors. And Charles was obviously terrified of his father, whose mannerisms he seemed condemned to imitate; pulling at his cuffs, clasping his hands, even walking with one arm behind his back.

As she entered the airy marble-floored hall, Lilibet had glanced without comment on the great silk Garter banner fixed to the ornate balcony. If she was surprised, in the drawing room of an abdicated monarch, to take tea under his full-length portrait in kingly robes and another of Queen Mary in all her splendour, she did not show it.

Philip had been another matter, lounging against the Louis XV sofa and gazing satirically around at the collection of Meissen pug dogs and Black Diamond and Gin-Seng, their panting real-life counterparts. ‘Is it true you’ve got one called Peter Townsend?’ he had smirked.

‘We used to,’ Wallis had answered levelly. ‘But we gave the Group Captain away.’

‘Ha. As did Margaret, of course.’

But afterwards, once the queen had left, David seemed annoyed.

‘Oh, David. You didn’t ask her about my HRH again?’ Exasperation and love twisted within Wallis. Surely he hadn’t wasted a precious – and final – personal interview with the sovereign on something so utterly pointless? The Windsors would never let her be a Royal Highness and she didn’t care anyway. But David did, passionately, and had spent a lifetime trying to bring it about.

Wordless, spent from the recent effort, he shook his head. But he was growling, trying to speak, and eventually she gathered that he had been irked by his doctor, Monsieur Thin, not being presented to Her Majesty. ‘He would have remembered it all his life.’

She shook her head. Oh, the irony. No one was ever more aware of the power of the Crown than David, who had been so eager to give it up.

He had lasted just nine days after that. On the night he died, black ravens, harbingers of death, sat in the bright leaves outside his window. They had come for him. When, much later, she was called by the nurse it was to see that Black Diamond, who always slept on his bed, now lay on the rug on the floor. The pug too knew what was about to happen. At 2.20 in the morning, the one-time King Edward VIII of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions Beyond the Seas, Emperor of India, breathed his last. It was 28 May 1972.

Chapter One

Honeymoon in Paris, 1928

The hotel room was dingy and had an odd smell. There was a brass double bed whose counterpane sagged in the middle. The floral wallpaper was faded, with rust-edged stains.

Two long windows looked out into the street. Wallis went across to them. The window opposite had dried-up plants and dirty curtains.

She had not expected Paris to look like this. All the way over on the boat from Dover she had imagined views of the Eiffel Tower. But Wallis was an optimist, and never more so than now. This was her wedding day. A fresh start. A new life.

There was a mirror on the wall by the window, positioned to throw light on the face. Critically, she examined hers. She was no longer young – thirty-four at her last birthday – but she looked pretty good, she thought. Poised, sleek, fashionable. And hopeful, most of all.

Her wedding outfit – primrose-yellow dress, sky-blue coat – made a colourful contrast to the glossy black hair centre-parted and curled in two ‘earphones’. In her pale face her lips were a bold slash of red. If, in her dark-blue eyes, there was still something sad behind the sparkle, that would not stay long. Everything would be fine from now on.

They had married that morning in London. At the Chelsea Register Office, as both were divorcees. But Wallis did not regret being unable to wed in church. She had done that the first time round, and to a cad. Ernest could not be more different. He was a fine, kind, honourable man, and she was a lucky woman.

A movement in the mirror caught her eye. She saw that the bellhop who had brought their bags up was still standing in the doorway, scratching himself.

‘Ernest,’ she prompted, smiling. ‘I think he expects a tip.’

Her new husband rummaged in his overcoat pocket and handed over a small coin. The boy looked at it, raised his eyebrows and disappeared.

Wallis heaved her suitcase on to her bed and snapped the locks open. In the dingy surroundings her dresses, new for the honeymoon, bolstered her feelings of optimism. She had bought them all for a song and altered them herself. She was clever with her needle and had once thought of a career in fashion. After the divorce, the idea of supporting herself, of becoming an independent woman, had strongly appealed.

But her shattered self-confidence and her lack of practical skills had made this more difficult than she expected. And once she met Ernest, she had abandoned the effort altogether. He had been a port in a storm, quite literally, as his family owned a shipping firm. When he announced he was leaving America for the London office, and asked her to marry him and come too, she had seized the chance to begin again.

She shook out a dress and thought about the great Paris fashion houses. She was keen to see them even if there was no chance of buying anything. Money was tight, hence the shabby hotel room. Hence the tiny stone in the ring on her finger, so small it struggled to catch the limited light.

The family firm was in trouble, although Ernest was determined to turn it round. There were also the alimony payments to his first wife and young daughter. He had thought that would annoy her, but it didn’t. On the contrary, she was pleased that he already had a child. She was in her early thirties and the prospect was fading, but after her own miserable childhood, she had no wish for one anyway. She felt sorry for the little stepdaughter whose life had been upended by her parents’ divorce. When Audrey came to stay with them in London, she would give her a good time. They would be friends.

She felt Ernest’s solid, reassuring presence behind her. He came close and put his large hands over hers. She leant her head back, into his chest, and relished, for a few moments, his tall broadness, the feeling of utter safety, of being cherished and protected.

‘Don’t do that now,’ he murmured into her shoulder. He meant the open case before her.

‘But I have to unpack. My things will be so creased.’ The cheap material needed to be hung to look good.

He pulled her closer. His moustache was tickling her neck. ‘Who cares if your things are creased? I’d like to crease them some more!’

Her reaction was as instant as it was unexpected. Panic swept through her like a tidal wave. An alarm bell shrilled loudly in her head and her heart rose in her throat, banging violently. The urge to wrench herself away was overwhelming and only by inhaling slowly, shudderingly, could she gain any control.

Ernest had not noticed. He was sliding his arms round, pressing his body into her back. Through his coat and jacket she could feel how aroused he was. ‘Wallis,’ he murmured into her ear. ‘I’ve wanted you for so long.’

As his hand explored her breast, her whole body screamed silently. Her teeth began to chatter. She clamped them hard together so he would not hear. He pushed her gently forward, on to the bed. She fell like a stone, hands by her side, and lay rigid, face pressed in the cover. Its sour smell filled her nostrils.

She braced herself, as if against some expected blow or other act of violence. Great waves of heat followed by sickening swirls of cold were chasing each other round her stomach. She could not breathe. She turned her head, gasped.

He seemed to take this as encouragement, perhaps as a pant of desire. His hand was on her thigh now. It was pulling up her dress; she could feel his fingers on her stocking top. She was going to be sick, she pressed her mouth and body hard into the bed. If those fingers got through, if they touched her …

Oh God, no. Please, no.

She must have spoken aloud. The fingers stopped. The hand pulled away. Beneath her ear, there was a grate and groan of bedsprings as he sat down. ‘Wallis, whatever’s the matter?’

She raised her head. He sat at the other side of her case, his overcoat still on. His basset hound face with its round brown eyes registered absolute bewilderment.

She could not blame him. Throughout their short courtship, kissing was as far as he had gone. He was the very pattern of chivalry and had treated her with the utmost respect. But on their wedding night he was naturally hoping for more. She was a divorcee, after all, a woman of experience. That he had absolutely no idea what her experience had been was not his fault.

Perhaps she should have told him, but what could she have said? That she had, for nine years, been married to someone who had beaten and abused her, who drank himself senseless, who had not only forced himself upon her but made her watch him with other women?

How could she have told him? Ernest would have been appalled; it would have lessened her in his eyes. It lessened her in her own. She had pushed her first husband into the depths of the furthest cupboard at the back of her mind, the one marked ‘The Past’, and done her best to forget all about him.