C m kornbluth, p.1

C M Kornbluth, page 1

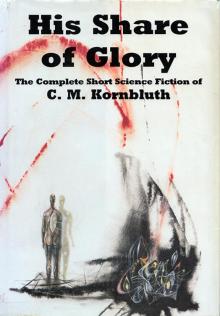

His Share of Glory

The Complete Short Science Fiction of C. M. Kornbluth

His Share of Glory contains all the short science fiction written solely by Cyril M. Kornbluth. Many of the stories are SF “classics,” such as “The Little Black Bag,” “Two Dooms,” “The Mindworm,” and, of course, “That Share of Glory.” There are fifty-six works of short SF, with the original bibliographic details including pseudonymous by-line.

The introduction is by Frederik Pohl, noted SF writer and life-long friend and collaborator of C. M. Kornbluth.

“For brilliant conceptions and literate use of words, for exciting imagination and characters to make it real, the science-fiction field is fortunate in many talented writers—but none better than he [C. M. Kornbluth].”

—Frederik Pohl

“Cyril has been one of the best writers in the business for a long time.”

—James Blish

For a complete list of books available from NESFA Press, please write to:

NESFA Press

P.O. Box 809

Framingham, MA 01701-0203

U.S.A.

Dust jacket illustration Copyright 1958 by Richard Powers; design by Suford Lewis, Ann Broomhead, and the Hertels.

Photo courtesy of Robert A. Madle, circa 1939

C. M. Kornbluth

Cyril M. Kornbluth (1923-1958) was a member of the Futurians (a group of SF writers and fans in the late 1930s, who greatly influenced the course of the Science Fiction field). Known for his insightful, cynical and humorous stories, he began writing professionally at the age of 15. As an infantryman in WW II, he fought in the Battle of the Bulge, for which he was decorated. He attended the University of Chicago before becoming a news wire-service reporter. Rising to become bureau editor, Kornbluth quit in 1951 to write full-time, but died of a heart attack at the age of 35. A prolific writer both in the SF field and other genres, he wrote over a hundred stories and twenty-eight books, by himself and with others. Kornbluth is best known for his collaborations, such as the Gunner Cade stories with Judith Merril. His more extensive collaborative work with Frederik Pohl resulted in such books as Critical Mass, Gladiator-At-Law, The Space Merchants and short stories like “Best Friend,” “The Castle on Outerplanet,” “The Engineer,” “A Gentle Dying,” “Gravy Planet,” “Mars-Tube,” and “Mute Inglorious Tam.” In 1973 Kornbluth and Pohl’s short story “The Meeting” won the Hugo award.

Copyrights

Copyright 1997 by the Estate of Cyril M. Kornbluth

Cyril

Copyright 1997 by Frederik Pohl

Editor’s Introduction

Copyright 1997 by Timothy P. Szczesuil

Dust Jacket Illustration

Copyright 1958 by the Estate of Richard Powers

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY ELECTRONIC, MAGICAL OR MECHANICAL MEANS INCLUDING INFORMATION STORAGE AND RETRIEVAL WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER, EXCEPT BY A REVIEWER, WHO MAY QUOTE BRIEF PASSAGES IN A REVIEW.

FIRST EDITION

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 95-067735

International Standard Book Number:

0-915368-60-9

Copyright Acknowledgments

The following stories appeared under the by-line of C. M. Kornbluth or one of the following pseudonyms: Edward J. Bellin, Cecil Corwin, Walter C. Davies, Simon Eisner, Kenneth Falconer, and S. D. Gottesman.

“That Share of Glory” first appeared in Astounding, January 1952.

“The Adventurer” first appeared in Space SF, May 1953.

“Dominoes” first appeared in Star Science Fiction Stories, edited by Frederik Pohl, Ballantine, 1953.

“The Golden Road” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, March 1942.

“The Rocket of 1955” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, April 1941.

“The Mindworm” first appeared in Worlds Beyond, December 1950.

“The Education of Tigress McCardle” first appeared in Venture, July 1957.

“Shark Ship” first appeared as “Reap the Dark Tide” in Vanguard, June 1958.

“The Meddlers” first appeared in SF Adventures, September 1953.

“The Luckiest Man in Denv” first appeared in Galaxy, June 1952.

“The Reversible Revolutions” first appeared in Cosmic Stories, March 1941.

“The City in the Sofa” first appeared in Cosmic Stories, July 1941.

“Gomez” first appeared in The Explorers by C. M. Kornbluth, Ballantine, 1954.

“Masquerade” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, March 1942.

“The Slave” first appeared in SF Adventures, September 1957.

“The Words of Guru” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, June 1941.

“Thirteen O’Clock” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, February 1941.

“Mr. Packer Goes to Hell” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, June 1941.

“With These Hands” first appeared in Galaxy, December 1951.

“Iteration” first appeared in Future, September/October 1950.

“The Goodly Creatures” first appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (F&SF), December 1952.

“Time Bum” first appeared in Fantastic, January/February 1953.

“Two Dooms” first appeared in Venture, July 1958.

“Passion Pills” first appeared in A Mile Beyond the Moon by C. M. Kornbluth, Doubleday, 1958.

“The Silly Season” first appeared in F&SF, Fall 1950.

“Fire-Power” first appeared in Cosmic Stories, July 1941.

“The Perfect Invasion” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, March 1942.

“The Adventurers” first appeared in SF Quarterly, February 1955.

“Kazam Collects” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, June 1941.

“The Marching Morons” first appeared in Galaxy, April 1951.

“The Altar at Midnight” first appeared in Galaxy, November 1952.

“Crisis!” first appeared in SF Quarterly, Spring 1942.

“Theory of Rocketry” first appeared in F&SF, July 1958.

“The Cosmic Charge Account” first appeared in F&SF, January 1956, and has appeared elsewhere as “The Cosmic Expense Account.”

“Friend to Man” first appeared in Ten Story Fantasy, Spring 1951.

“I Never Ast No Favors” first appeared in F&SF, April 1954.

“The Little Black Bag” first appeared in Astounding, July 1950.

“What Sorghum Says” first appeared in Cosmic Stories, May 1941.

“MS. Found in a Chinese Fortune Cookie” first appeared in F&SF, July 1957.

“The Only Thing We Learn” first appeared in Startling Stories, July 1949.

“The Last Man Left in the Bar” first appeared in Infinity, October 1957.

“Virginia” first appeared in Venture, March 1958.

“The Advent on Channel 12” first appeared in Star Science Fiction Stories No. 4, edited by Frederik Pohl, Ballantine, 1958.

“Make Mine Mars” first appeared in SF Adventures, November 1952.

“Everybody Knows Joe” first appeared in Fantastic Universe, October/November 1953.

“The Remorseful” first appeared in Star Science Fiction Stories No. 2, edited by Frederik Pohl, Ballantine, 1954.

“Sir Mallory’s Magnitude” first appeared in SF Quarterly, Winter 1941/1942.

“The Events Leading Down to the Tragedy” first appeared in F&SF, January 1958.

“King Cole of Pluto” first appeared in Super Science Stories, May 1940.

“No Place to Go” first appeared in Cosmic Stories, May 1841.

“Dimension of Darkness” first appeared in Cosmic Stories, May 1941.

“Dead Center” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, Febrary 1941.

“Interference” first appeared in Cosmic Stories, July 1941.

“Forgotten Tongue” first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, June 1941.

“Return From M-15” first appeared in Cosmic Stories, March 1941.

“The Core” first appeared in Future, April 1942.

The editor dedicates this book to

All the Members of

The New England Science Fiction Association

without whom this book would not be possible.

Contents

Cyril by Frederik Pohl

Editor’s Introduction

That Share of Glory

The Adventurer

Dominoes

The Golden Road

The Rocket of 1955

The Mindworm

The Education of Tigress McCardle

Shark Ship

The Meddlers

The Luckiest Man in Denv

The Reversible Revolutions

The City in the Sofa

Gomez

Masquerade

The Slave

The Words of Guru

Thirteen O’Clock

Mr. Packer Goes to Hell

With These Hands

Iteration

The Goodly Creatures

Time Bum

Two Dooms

Passion Pills

The Silly Season

Fire-Power

The Perfect Invasion

The Adventurers

Kazam Collects

The Marching Morons

The Altar at Midnight

Crisis!

Theory of Rocketry

Friend to Man

I Never Ast No Favors

The Little Black Bag

What Sorghum Says

MS. Found in a Chinese Fortune Cookie

Fhe Only Thing We Learn

The Last Man Left in the Bar

Virginia

The Advent on Channel Twelve

Make Mine Mars

Everybody Knows Joe

The Remorseful

Sir Mallory’s Magnitude

The Events Leading Down to the Tragedy

Early “to spec” Stories

King Cole of Pluto

No Place to Go

Dimension of Darkness

Dead Center

Interference

Forgotten Tongue

Return from M-15

The Core

Cyril

by

Frederik Pohl

In the late 1930s a bunch of us New York City fans, tiring of being members of other people’s fan clubs, decided to start our own. We called it “the Futurians.” As nearly as I can remember the prime perpetrators were Don Wollheim, Johnny Michel, Bob Lowndes and myself, but we quickly acquired a couple of dozen other like-minded actifans and writer wannabees, and among them was a pudgy, acerbic fourteen-year-old from the far northern reaches of Manhattan whose name was Cyril Kornbluth.

All the Futurians had an attitude; it was what made us so universally loved by other New York fans. Even so, Cyril was special. He had a quick and abrasive wit, and he exercised it on anyone within reach. What he also had, though, was a boundless talent. Even at fourteen, Cyril knew how to use the English language. I think he was born with the gift of writing in coherent, pointed, colorful sentences, and, although I don’t think any of his very earliest writing survives, some of the stories in this book were written when he was no more than sixteen.

Most of what Cyril wrote (what all of us Futurians wrote, assiduously and often) was science fiction, but he also had a streak of the poet in him. Cyril possessed a copy of a textbook—written, I think, by one of his high-school teachers—which described all the traditional forms of verse, from haiku to chant royale, and it was his ambition to write one of each. I don’t think he made it. I do remember that he did a villanelle and several sonnets, both Shakespearean and Petrarchan, but I don’t remember the poems themselves. All I do remember of Cyril’s verse is a fragment from the beginning of a long, erotic poem called “Elephanta”—

How long, my love, shall I behold this wall

Between our gardens, yours the rose

And mine the swooning lily?

—and a short piece called “Calisthenics”:

One, two, three, four,

Flap your arms and prance

In stinky shirt and stinky socks

And stinky little pants.

By 1939 a few of the Futurians had begun making an occasional sale to the prozines. Then the gates of Heaven opened. In October of that year I fell into a job editing two science-fiction magazines for the great pulp house of Popular Publications; a few months later Don Wollheim persuaded Albing Publications to give him a similar deal, while Bob Lowndes got the call to take over Louis Silberkleit’s magazines. These were not major markets. None of us had much to spend in the way of story budgets—Donald essentially had no budget at all—and we were at a disadvantage in competing with magazines like Amazing, Astounding and Thrilling Wonder for the work of the established pros. What we did have, though, was each other, and all the rest of the Futurians.

I think Cyril’s first published story was a collaboration with Dick Wilson, “Stepson of Space,” published under the pseudonym of “Ivar Towers” (the Futurian headquarters apartment was called “the Ivory Tower”) in my magazine, Astonishing Stories. He and I also collaborated on a batch of not very good stories for my own magazines, mostly bylined “S. D. Gottesman” at Cyril’s prompting—I think he was getting back at a hated math teacher of that name—but his solo work, under one pen-name or another, generally appeared in Don Wollheim’s Stirring and Cosmic. Most of them are herein.

Then the war came along.

Cyril, who had worked now and then as a machinist, got into uniform as an artillery maintenance man, working in a machine shop far behind the lines to keep the guns going. He probably could have survived the war in relative comfort there, except that the Army had an inspiration. In its wisdom it imagined that the war would go on for a good long time, that it would need educated officers beyond the apparently available supply toward its final stages and that it would be a good idea to send some of its brighter soldiers to school ahead of time. The program was called “ASTP,” and Cyril signed up for it at once. It was a very good deal. Cyril went back to school at the Army’s expense quite happily…until the Army noticed that the war was moving toward a close faster than they had expected, with some very big battles yet to be fought. The need was not for future officers but for present combat troops. They met it by canceling ASTP overnight and throwing all its members into the infantry, and so Cyril wound up lugging a 50-caliber machine gun through the snows of the Battle of the Bulge.

The war did finally end. We all got back to civilian life again, and Cyril moved to Chicago to go back to school, at the University of Chicago, on the G.I. Bill. Meanwhile Dick Wilson had also wound up there as a reporter for the news wire service Trans-Radio Press; he was their bureau chief for the city, and when he needed to hire another reporter he gave the job to Cyril. For a couple of years Cyril divided his time between the news bureau and the university, somehow finding enough spare hours to write an occasional short story for the magazines (all of them herein).

Then he came east on a visit. He stayed at our house just outside of Red Bank, New Jersey, for a while, and I was glad to see him because I needed help on a project.

The project was a novel I had begun about the future of the advertising business. I had been working on it desultorily for a year or so and succeeded in getting about the first third of it on paper. I showed that much to Horace Gold, then the editor of Galaxy, and Horace said, “Fine. I’ll print it as soon as I finish the current serial.” “But it isn’t finished,” I said. “So go home and finish it,” said Horace.

I didn’t see how that was possible in the time allowed, and so Cyril’s arrival was a godsend. When I showed what I had to him and suggested we try collaborating again he agreed instantly; he wrote the next third by himself, and the two of us collaborated, turn and about, on the final section. After some polishing and cleaning up of loose ends we turned it in and Horace ran it as “Gravy Planet”; a little later Ian Ballantine published it in book form as The Space Merchants and so it has remained, in many editions and several dozen translations, ever since.

Working with Cyril Kornbluth was one of the great privileges of my life. First to last, we wrote seven novels together: The Space Merchants, Gladiator-at-Law, Search the Sky and Wolfbane in the field of science fiction, plus our three “mainstream” novels, Presidential Year, A Town Is Drowning and Sorority House (that last one published under the pseudonym of “Jordan Park”). I can’t say that we never quarreled about anything—after all, we were both graduates of the feisty Futurians—but the writing always, always went quickly and well. As editor, agent and collaborator I have worked with literally hundreds of writers over the years, in one degree or another of intimacy, but never with one more competent and talented than Cyril. Even when we were not actually collaborating we would now and then help each other out. Once when Cyril complained that he wanted to write a story but couldn’t seem to come up with an attractive idea, I reminded him that he had once mentioned to me that he’d like to write a story about medical instruments from the future somehow appearing today; “The Little Black Bag” was the result. And after that was published I urged him to do more with the future background from which those instruments had come, and that turned into “The Marching Morons.” And I am indebted to him for any number of details, plot twists and bits of business in my own stories of the time.

All the while we were writing together, of course, he had other irons in the fire. With Judy Merril he wrote two novels, Marschild and Gunner Cade; he continued to pour out his own wonderful shorter pieces, and he wrote half a dozen novels all his own. Some of them were mainstream—Valerie, The Naked Storm and Man of Cold Rages—but three were science fiction. They were, of course, brilliant. They are also, however, sadly, somewhat dated; Takeoff was all about the first spaceflight, Not This August about the results of the anticipated Russian-American World War III, which in his story the Russians had won. By 1958 he had larger plans, with two novels in the works. Neither was science fiction; both were historical. One was to be about the life of St. Dacius, and that is all I know about it; if any part of it was ever on paper it has long since been lost. The other was to be about the battle of the Crater in the Civil War, and for that one Cyril had done an immense quantity of research. He completed several hundred pages of notes and reference material…but that’s as far as it got. The Battle of the Bulge finally took its toll.