Roxy, p.1

Roxy, page 1

-

A blast of a trip through revenge and grief

Roxy’s life is turned upside down when her husband is killed in a car crash, his naked body found entangled with his lover’s. Twenty-seven-year-old Roxy is left behind with their daughter, her husband’s personal assistant, and their babysitter to come to terms with this shameful end to her marriage. Looking to break free from her grief, Roxy takes the three of them on an impromptu road trip filled with darkly humorous observations about loss, parental responsibility, and the expiration date of love. Through masterful dialogues and in her trademark lucid style, Gerritsen introduces the reader to a woman whose response to grief both shocks and endears.

-

Praise for Roxy

‘A novel you devour in one sitting: elegiac, beautiful, and very strong.’

HERMAN KOCH, author of The Dinner

‘Roxy is a novel to read slowly—like a good wine is to be savored rather than drank down in one gulp.’

Het Parool

‘Some sentences in Roxy are as if carved in stone; like Samuel Beckett, Gerritsen knows how to capture moments of terrifying precision and darkness.’

De Morgen

‘In her fifth book Esther Gerritsen has continued to grow to the level of an author who dares to incorporate everything—from comical cross-talk to heartrending silence. Once again, she displays her gift for striking sentences and dialogue that teeters on the thin line between normality and alienation, between entertaining kookiness and harrowing absurdism.’

De Volkskrant

‘An excellent new novel from Gerritsen written with indestructible good cheer.’

NRC Handelsblad

‘Even more than we have grown used to, in Roxy Gerritsen strips her scenes and language to the bone, leaving us with the core, which is ridiculously good.’

OPZIJ LITERATURE PRIZE

‘The stories of Esther Gerritsen, one of the best Dutch writers for years, are always extreme, dramatic, and confrontational. What is so special about Gerritsen’s work is that within a somewhat outrageous story she wraps a deeper, existential message.’

Trouw

‘Not only in her choice of subjects but also in her feeling for style, Gerritsen is one of a kind. Her absurdist logic and subtle humoristic voice make every sentence in her novels and columns a “typical Gerritsen.”’

JURY, FRANS KELLENDONK PRIZE

‘Esther Gerritsen´s characters have their own, extremely unique way of viewing the world.’

Vogue

Praise for Craving

‘The lives of others, in all their peculiarity, are given sympathetic scrutiny in this diverting European oddity, in cool prose and naturalistic dialogue.’

Kirkus Reviews

‘I don’t know if I’ve ever read a novel that captures the emotional labor of people-pleasing language quite so well … Droll and horrific and incredibly moving.’

New York Times

‘Cool, sparse, and delicious, Esther Gerritsen’s Craving hits all the right notes. This is an author who is unafraid of both complex characters and complex emotion (Thank God!).’

ALICE SEBOLD, author of The Lovely Bones

-

ESTHER GERRITSEN is a Dutch novelist, columnist, and playwright. She made her literary debut in 2000. She is one of the most widely read and highly praised authors in the Netherlands, and makes regular appearances on radio programs and at international literary festivals, such as Litquake and Wordfest. Esther Gerritsen had the honor of writing the Dutch Book Week gift in 2016, which had a print run of 700,000 copies. In 2014 she was awarded the Frans Kellendonk Prize for her entire oeuvre. Her novel Craving was shortlisted for the Vondel Prize and was published in the US in September 2018. Roxy has sold over 20,000 copies in the Netherlands and was shortlisted for the Libris Literature Prize.

MICHELE HUTCHISON studied at UEA, Cambridge, and Lyon universities and worked in publishing for a number of years. In 2004, she moved to Amsterdam. Among the many works she has translated are La Superba by Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer, Fortunate Slaves by Tom Lanoye, Craving by Esther Gerritsen, and An American Princess by Annejet van der Zijl. She also co-authored the successful parenting book, The Happiest Kids in the World.

-

AUTHOR

‘I asked myself the question: What happens when a woman is furious but there is no enemy in sight? Roxy materialized out of this consideration.’

TRANSLATOR

‘I felt an immediate affinity with Esther Gerritsen’s writing, so translating her is always a delight. In Roxy I love the smart sense of dialogue and the badinage between the characters; and while working on the translation I often found myself reading it out loud to check I had retained Gerritsen’s natural flow of speech.’

PUBLISHER

‘Esther Gerritsen stands out as one of the most original voices in Dutch literature. Her characters are driven by irrational and instinctive forces, which find their sources in grief, anger, and despair. Her writing is astute, funny, daring, and full of life; and discomfits the reader in a way only great literature is able.’

-

ESTHER GERRITSEN

ROXY

Translated from the Dutch

by Michele Hutchison

WORLD EDITIONS

New York, London, Amsterdam

-

Published in the USA in 2019 by World Editions LLC, New York

Published in the UK in 2016 by World Editions Ltd., London

World Editions

New York/London/Amsterdam

Copyright © Esther Gerritsen, 2014

English translation copyright © Michele Hutchison, 2016

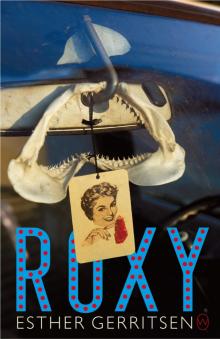

Cover image © Patrice Hauser

Author portrait © Paulina Szafrańska

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data is available

ISBN Trade paperback 978-1-64286-040-5

ISBN E-book 978-1-64286-048-1

First published as Roxy in the Netherlands in 2014 by De Geus

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the Dutch Foundation for Literature

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Twitter: @WorldEdBooks

Instagram: @WorldEdBooks

Facebook: WorldEditionsInternationalPublishing

www.worldeditions.org

Book Club Discussion Guides are available on our website.

-

Dost thou behold

How I, stout heart and bold,

I, the undaunted once in open battle,

Lay violent hands on unsuspecting cattle?

Alas for scorn! How am I put to shame!

Sophocles, Ajax, translation by Sir George Young

-

THERE ARE TWO of them: a man and a woman. The man asks her if she is Roxy—a strange policeman saying her name in the middle of the night. Yes, she is. Can they come in? Roxy would rather they didn’t.

She assumes the worst: her husband could be dead. He’s always worrying about having a heart attack. He has the risk factors. This way, the news can only be better than expected. And the policeman will have already come out with it.

Roxy waits for the moment of relief, but her husband is dead and after that there’s nothing to be relieved about. She says, ‘Well, come on in then.’

She doesn’t like having strangers in the house. Half a day can be wasted on a washing-machine repairman. First there are the hours spent waiting for the stranger, then the house no longer belongs to her. When the man finally rings the bell and she opens the door, all the oxygen in the house escapes. She’s friendly to the washing-machine repairman—cracking jokes, making coffee, smiling a lot. She pays and gives him an appropriate tip. But it all seems to take place under water; you can’t keep it up for long.

‘Sit down,’ Roxy says. She points at the bar stools. The bar was her idea. Arthur gave her permission. Arthur doesn’t like her saying he ‘allowed’ her to do something. The bar stools are for people who drop by, drink coffee for an hour and then leave. It’s rare anyone stays an hour.

The policeman and woman sit down and now it’s Roxy’s turn to talk, cry, ask questions, maybe even scream. She wonders what they are expecting. She has reluctantly allowed these strangers in, but she understands this can’t be dealt with quickly. She can’t nod politely, say, ‘thanks for the information’ and rush them out the door—this is going to take time.

She hasn’t realized she’s been holding her breath; now she gasps for air. But the only thing that goes in is water, and she chokes on stifled tears.

She tries to say, ‘I can’t,’ but of course she can and soon she is breathing in this world, just like the others. Okay, so this is going to take a while.

‘I’ll fetch my dressing gown.’

She goes upstairs and quietly enters her daughter’s bedroom. The child is lying on her stomach. Roxy lays her hand on her daughter’s back and waits until she can feel the life in the small body.

When she’s back in

‘My dressing gown.’ She goes back upstairs.

The younger of the two police officers—the woman—looks anxious. Roxy doesn’t envy her.

‘Have you had to do this before?’

The man nods.

‘And you?’

‘No.’ The policewoman smiles and Roxy is grateful because it’s the first time for both of them.

Their total lack of haste is remarkable; their calm says that everything has already happened.

‘Now what?’ She looks at the man.

‘You can go to him … see him. We’ll take you.’

‘He is dead, isn’t he?’ Roxy says, shocked, as though she hadn’t understood and was actually supposed to be hurrying.

‘Yes,’ the man says, ‘he’s dead. He died on the spot and was taken to the hospital mortuary. We can take you there.’

‘My daughter. She’s sleeping.’

‘How old is your daughter?’

‘Three.’

‘Can’t you ask a babysitter to come? Family member?’

‘My family live a long way away.’

‘Neighbours?’ She shakes her head and doesn’t say that the girl next door, an economics student, picks up her daughter and babysits her practically every day. She even has a key. Although all three of them are breathing in the same space, they remain strangers, and naturally she lies to strangers. It doesn’t occur to her to say she’d do anything except leave her daughter, wake her up, unsettle her.

‘Do I have to go to the hospital?’

‘Nothing’s compulsory,’ the man says.

‘You have to call someone,’ the woman says.

‘It’s late,’ Roxy says. ‘Everyone’s in bed.’

‘There are times when it’s all right to wake people up. You have to call someone, madam.’

‘All right.’ Roxy looks outside. ‘It’s almost full moon.’

It’s silent for a moment. Everyone looks outside and the young policewoman says, ‘Yes, almost.’

‘You’re the one who wrote that book, aren’t you?’ the man says.

Roxy knows which book he means. There’s only one book people know—her first—but she can’t resist saying: ‘Which book? I’ve written three.’

‘With the truck on the front.’

She nods.

‘Fancy that,’ he says.

‘Do you want a drink?’

‘We’ll wait here with you until you’ve called someone.’

Roxy feels a rush of fear. ‘You don’t have to leave on my account.’

‘Just make the call.’

‘My phone’s upstairs.’

‘We’ll wait here.’

She goes upstairs again. She doesn’t know who to call in a situation like this. She can’t think of anyone other than Arthur. She goes into their bedroom. The telephone is on her bedside table: she likes to have it within reach. She sits down on the bed, takes the phone and stares at it, a pointless thing now. She lets it slip through her fingers and waits until enough time has passed for her to have called someone.

She stands facing the two police officers in her kitchen. As soon as she says she’s called someone they’ll go. She shouldn’t have lied about the babysitter. She shouldn’t have been so silly about the book. The intruders have become her forsakers at an inconceivable rate of knots.

There’s a business card on the kitchen table.

‘Did you make the call?’

‘Yes, my … somebody … somebody’s coming.’

They get up.

‘Won’t you have a drink?’ They could be friends.

‘How did you meet?’ people would ask later.

‘Yes, it’s an unusual story,’ she’d say. ‘They were the ones who came to tell me about Arthur’s accident. They stayed the entire night afterward. They’d read my books—that was nice. We drank the wine that Arthur had stored right at the bottom of the rack in the basement, the expensive bottles.’

The man says, ‘My colleague will come and see you again early tomorrow morning. Okay?’

‘Okay,’ Roxy says. ‘Lovely.’

Roxy doesn’t ask herself how you tell a three-year-old something like this—you just say it. She sits on the bar stool in the open kitchen and knows she’ll have to wait until her daughter wakes up before she tells her. Louise has a father for one last night.

The counter is spotless. It’s Wednesday; the cleaner has been. The espresso machine Roxy struggles with shines. All of this belongs to just her now. The house has become alien in one swift blow. They’d never owned it together: she’d lived in his house.

She mentally runs through her possessions, beginning with the kitchenware, then the furniture, the house, the car (the Camaro was a total write-off of course, but she still has the SUV), the bank accounts. If you’ve never taken care of yourself, it’s a scary mystery how you accumulate goods. It’s inconceivable that you might have qualities, or be able to do things that people would pay good money for.

When she was seventeen, she left home carrying two weekend bags. She didn’t look back. Arthur would be waiting around the corner to pick her up. It was a golden ticket that left no room for doubts. Arthur arrived twenty minutes after the agreed time. That wasn’t right, she thought at the time. It was a bad sign. Like James Bond, she had to step from one flying aeroplane onto another—a perilous stunt but not impossible—but the plane you step onto can’t coolly turn up twenty minutes late.

Twenty minutes of freefall on the corner of Saint Vitus Street and the Molenhof.

Ten years later she falls even further. She sits calmly on the bar stool at three in the morning, wide awake, searching for ideas, comparisons. She has spent years of her life sitting in her study pondering these kinds of metaphors. She can spend an entire afternoon working on a sentence and be happy. Although, on those tranquil afternoons, she has an increasing sense that she won’t be able to get away with this much longer.

She has always known that she skipped something, took a short cut to adulthood. Now they’re coming to get me, she thinks. Now I have to go back, and of course she doesn’t call anybody. Not only to her daughter is Arthur not dead yet, but also to Roxy herself. Roxy is happy, one more night, one last hour.

The darkness does its work. She’s lying in bed; she has turned off the light but her eyes are still open and she is afraid. She screams into her pillow so as not to wake her daughter.

Before she falls asleep, she hears the birds. She is awoken by her daughter’s voice.

‘It’s morning,’ Louise cries, ‘the sun has risen!’ It’s a line she must have remembered from a story, a film. For the last few weeks, that strange, complete sentence has been coming from her daughter’s bedroom: It’s morning; the sun has risen.

-

THEY ARE IN the kitchen when Liza, the babysitter, lets herself in. It’s Thursday, one of the days Arthur used to look after their daughter. Arthur insisted they share the childcare. He was proud that he was doing half of it, which meant that he arranged half of it. Liza came on his days with Louise.

‘Good morning,’ Liza says.

‘Daddy is dead,’ Louise says. ‘We’re eating pancakes.’

That morning she’d lifted her daughter out of bed, taken her into her own, and waited patiently until she was properly awake.

‘Daddy working?’ Louise was used to him being away a lot, yet she often asked after him.

‘No,’ Roxy said. ‘I have to tell you something. Daddy is dead. He had an accident in the car and now he can’t come back to us.’

The girl looked frightened and said, ‘Don’t be silly.’

The concept of death was brand new. She’d seen her father swatting flies—it had interested her. She’d wanted to look at the dead insects.

Later, she’d called out to her mother: ‘I will make you dead,’ and when that had been forbidden, she’d tried again: ‘You are dead,’ but that wasn’t allowed either. So on that morning, when her mother said that her father was dead, it was breaking all the rules.