The best american poetry.., p.1

The Best American Poetry 2024, page 1

Praise for The Best American Poetry

“Each year, a vivid snapshot of what a distinguished poet finds exciting, fresh, and memorable: and over the years, as good a comprehensive overview of contemporary poetry as there can be.”

—Robert Pinsky

“The Best American Poetry series has become one of the mainstays of the poetry publication world. For each volume, a guest editor is enlisted to cull the collective output of large and small literary journals published that year to select seventy-five of the year’s ‘best’ poems. The guest editor is also asked to write an introduction to the collection, and the anthologies would be indispensable for these essays alone; combined with [David] Lehman’s ‘state-of-poetry’ forewords and the guest editors’ introductions, these anthologies seem to capture the zeitgeist of the current attitudes in American poetry.”

—Academy of American Poets

“A high volume of poetic greatness… in all of these volumes… there is brilliance, there is innovation, there are surprises.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A year’s worth of the very best!”

—People

“A preponderance of intelligent, straightforward poems.”

—Booklist

“A ‘best’ anthology that really lives up to its title.”

—Chicago Tribune

“An essential purchase.”

—The Washington Post

“For the small community of American poets, The Best American Poetry is the Michelin Guide, the Reader’s Digest, and the Prix Goncourt.”

—L’Observateur

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

DAVID LEHMAN was born in New York City in 1948, the son of Holocaust survivors. A graduate of Stuyvesant High School and Columbia University, he spent two years at Clare College, Cambridge, as a Kellett Fellow. Upon his return to New York, he worked as Lionel Trilling’s research assistant and earned his PhD at Columbia with a thesis on prose poems. He taught for four years at Hamilton College, and then, after a postdoctoral fellowship at Cornell, he turned to writing as a full-time occupation. Lehman launched The Best American Poetry series in 1988. He edited The Oxford Book of American Poetry (2006). The Morning Line (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021) is the most recent of his poetry collections; his prose books include The Mysterious Romance of Murder (Cornell University Press, 2022), One Hundred Autobiographies: A Memoir (Cornell, 2019), and Signs of the Times: Deconstruction and the Fall of Paul de Man (Simon & Schuster, 1991). In 2010 he received the Deems Taylor Award from the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) for A Fine Romance: Jewish Songwriters, American Songs (Schocken, 2009). Lehman lives in New York City and in Ithaca, New York.

FOREWORD by David Lehman

Lord Byron had a knack for the clever stanza-closing couplet in Don Juan, his comic masterwork, but his lines on John Keats’s death miss the mark. “ ’Tis strange, the mind, that very fiery particle, / Should let itself be snuffed out by an article,” Byron wrote. The Quarterly Review did trash Keats’s efforts. But he died young—shy of his twenty-sixth birthday—not from insult but from an acute case of consumption. He knew he was dying. “An English winter would put an end to me, and do so in a lingering hateful manner,” Keats wrote in a letter to the slightly older Percy Bysshe Shelley. “Therefore, I must either voyage or journey to Italy, as a soldier marches up to a battery.” In Italy he died.

Asked to name the first poem that profoundly moved them, some readers opt for Keats’s “When I Have Fears,” which he wrote in January 1818, just three years before his death from tuberculosis. Even if you didn’t know that Keats died at age twenty-five, this immortal sonnet is bound to affect you. No other poem treats the fear of death, and in particular an untimely death, in so noble a fashion:

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain,

Before high-piled books, in charact’ry,

Hold like rich garners the full-ripen’d grain;

When I behold, upon the night’s starr’d face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour!

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love!—then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.

Adhering to the structure of a Shakespearean sonnet, the poem consists of just one sentence stretched over fourteen lines. The first twelve advance the theme in three four-line movements (beginning “When,” “When,” and “And when”). The eloquent closing couplet provides the “then” on which all these dependent clauses rest. It raises the poem from trepidation to a kind of visionary heroism.

Keats wastes no time. He opens with startling directness, ten monosyllables in a row: “When I have fears that I may cease to be.” Then he turns to metaphor: “Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain.” Keats uses the verb “to glean” in its original sense of “to gather for a harvest.” The “pen” and “brain” specify that it is a writer who is contemplating his demise, but “glean’d” does double duty, likening the act of writing to that of bringing forth the fruit of the earth.

A rich simile concludes the first movement of the poem: “Before high-piled books, in charact’ry, / Hold like rich garners the full-ripen’d grain.” Keats uses “in charact’ry” as we would say “in print”; he is imagining the grandeur of publication. Note the double alliteration—“rich garners,” “ripen’d grain”—that makes the line so characteristic of a poet whose words you can almost taste. Or would, if you possessed the “strenuous tongue” that “can burst Joy’s grape against his palate fine,” to quote from Keats’s “Ode on Melancholy.”

The sonnet’s second movement changes the metaphorical terrain from earth to sky, from writing to seeing, and from books to stars: “When I behold, upon the night’s starr’d face, / Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance.” The very word “romance” signals the theme of the poem’s third movement. From stellar glory we move to “unreflecting love,” the love of a “fair creature of an hour,” a love doomed to go unfulfilled, unrequited.

In his masterly study Shakespeare, the scholar and poet Mark Van Doren argued that the weak part of a Shakespeare sonnet may be its closing couplet.1 Not here. “Then on the shore / Of the wide world I stand alone, and think / Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.” As he positions himself at the edge of the world, in intense contemplation of a dire fate, Keats arrives at a transcendent moment. He transports himself into an almost palpable “nothingness” that makes all hope of “love and fame” seem somehow vain and irrelevant. It is as if the poet can feel, can “think” his way into feeling, the annihilation of consciousness—as if he can apprehend the oblivion that he intends to meet head-on. The subtle pauses between these lines enhance their impact. The couplet exists in counterpoint to this amazing sentence from the last of his deathbed letters: “I have an habitual feeling of my real life having past, and that I am leading a posthumous existence.”

In another of his poignant and profound letters, Keats develops his concept of “negative capability,” a phrase that has launched a thousand fellowships. Keats explains that “the excellence of every art is its intensity, capable of making all disagreeables evaporate.” The observation can help to illuminate the logic of his otherwise hard-to-grasp assertion that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” King Lear is Keats’s example of how greatness of poetry can transform ugly truth into artistic beauty.

“When I Have Fears” is a second example of Keats’s negative capability in practice. Keats describes his fears in a heartbreaking way. But it is as if he can produce verbally what he will not be able to experience. His intensity, his acceptance of what fate has in store, and his fearless resolution substantiate Lionel Trilling’s belief that Keats exemplified nothing less than “the poet as hero.”

* * *

Some things don’t change. It seems someone is always announcing the death of poetry with nearly the same breathless urgency of Nietzsche asserting the demise of God. “Poetry Died 100 Years Ago This Month” ran the headline of a piece in The New York Times on December 29, 2022. Matthew Walther, the author, goes over previous “autopsy reports,” before trotting out his own theory, which is that T. S. Eliot “finished poetry off” in The Waste Land (1922). “The problem,” Walther contends, “is not that Eliot put poetry on the wrong track. It’s that he went as far down that track as anyone could, exhausting its possibilities and leaving little or no work for those who came after him.” The statement leaves unclear whether the “track” Eliot went down was either the wrong one or possibly a poetics equal to the disjunctions of modern life. In any case, as Walther sees it, poetry has disappeared, except perhaps for MFA progr

Poetry claimed its honorable place in one of the year’s most celebrated films, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. The physicist who supervised the building of the atom bomb came up with “Trinity” as a code name for the first test in July 1945. Why? Because of John Donne’s “Holy Sonnet #14,” which the movie quotes. The poem begins “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.” Full of paradox in Donne’s best manner—“Take me to you, imprison me, for I, / Except you enthrall me, never shall be free”—the sonnet is quite apt for the intense contradictory impulses in J. Robert Oppenheimer’s mind.

To poetry I turn for relief from the ferocity of hatred that has come more and more to define our public discourse. Poetry, especially great poetry, is my favored mode of resistance in the teeth of bestial violence, rabid tribalism, false accusations, and the shaming that is our digital equivalent of the ritual stoning undergone by Tessie Hutchinson, the unlucky woman who draws the slip marked with the black spot in Shirley Jackson’s story “The Lottery.”

Only in the dialogue between reader and writer can poetry defeat its enemies: rage, terror, dread, prejudice, cruelty, greed, violence. No poem will end a war, or protect the innocent who are its casualties, but all art worthy of the name stands up for life, love, the act of creation, the liberty of the mind, the vital realm of the imagination. Poetry, in Wallace Stevens’s words, presses back against “the pressure of reality.” Stevens argues that “individuals of extraordinary imagination” can “cancel” the pressure by resisting it. Like all stays against confusion, it is momentary in its consolation though immortal as a source of inspiration.

* * *

Nobel laureate Louise Glück, wonderful poet and friend, died at the age of eighty on Friday the 13th of October 2023. Louise edited The Best American Poetry 1993, and the experience of working closely with her—primarily by old-fashioned mail and the occasional phone call—was unforgettable. She took on the job despite a natural inclination to remain “on the sidelines, preferably the very front of the sidelines.” In a moment of moral clarity characteristic of Louise, she recognized that “continuous refusal to expose my judgment to public scrutiny seemed vanity and self-protection.” When the year began, Louise clamored for literary magazines “like a person in a restaurant banging the table for service,” in her words. They came, so many you could fill a small office with them.

Louise proved herself to be a peerless close reader of poems, and when I said this to her, she, usually distrustful of compliments, seemed genuinely touched. She chose the contents of the volume with “the generosity on which exacting criticism depends.” And she paid me the compliment of treating me like a partner in the enterprise; her decisions were final, but she welcomed discussion, and it was fun exchanging views.

In a biographical note written for the Nobel Prize committee, Louise wrote that growing up she was good at school, not so good at “the social world,” and that during adolescence she felt “ostracized” everywhere but summer camp. As a student at Columbia, she came under the influence of Stanley Kunitz, who championed her work. His “endorsement of high ambition” continued to inspire her, though “there was a deep fissure” with her erstwhile mentor when she strove to banish figurative language from the poems in her 1990 book, Ararat. It signaled a new direction for her, and it was precisely the poems in Ararat and in the volume that succeeded it, The Wild Iris, that made me feel that Louise was writing the best poems of her life and we would be lucky if she agreed to take the helm of the 1993 edition of The Best American Poetry. In a moving remembrance in The Paris Review, Elisa Gonzalez wrote, “I trace what feels like her love for me. She read. She listened. She critiqued. She encouraged. She nagged. Her faith in me exceeded my faith in myself.”

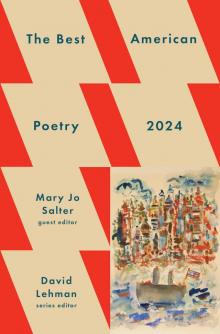

In this year’s Best American Poetry, we have a three-line poem by Louise Glück, “Passion and Form,” in addition to work by other poets who have served as guest editors in this series as long ago as 1991 and as recently as 2023: in chronological order, Mark Strand, Rita Dove, Yusef Komunyakaa, Paul Muldoon, Billy Collins, Heather McHugh, Kevin Young, Terrance Hayes, Dana Gioia, and Elaine Equi. We have poems that embrace the fruitful exigencies of rhyme and form: the sonnet sequence, the Rubáiyát stanza, couplets, haiku stanzas, free verse that lends itself to two-line or three-line stanzas, a meditation on the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins. There are arresting titles: “Satan’s Management Style,” “Wallace Stevens Comes Back to Read His Poems at the 92nd Street Y.” I regret that I could not prevail upon Mary Jo Salter, our guest editor, to choose “The Mailman,” a poem of hers that exemplifies the virtues that made me feel she would be an excellent editor for the BAP series.

Mary Jo has abundant editorial experience. After graduating from Harvard, where she studied with Elizabeth Bishop, she read for The Atlantic and was one of the first to recognize Amy Clampitt’s brilliance. As poetry editor at The New Republic, she got used to having sacks of submissions deposited on her doorstep. As an editor of the hugely influential Norton Anthology of Poetry, she understands the demands and complexities of putting together an ambitious anthology. She writes beautifully on the poets she loves. In an essay on W. H. Auden published last year in Literary Matters, she reveals the secret of the last line in his “Epitaph on a Tyrant”: “And when he cried the little children died in the streets.”2

It is as a poet that Mary Jo Salter has distinguished herself among her contemporaries. She uses the conventions and devices of poetry to confront, with rare humility, the radical changes and problems we face in the twenty-first century. A humane and compassionate intelligence informs her work. She writes with subtlety, self-awareness, and an utter delight in wordplay. Errors of speech can function as implicit metaphors, as in “Last Words,” which appeared on the BAP blog on January 20, 2023:

Forgive me for not writing sober,

I mean sooner, but I almost don’t

dare see what I write, I keep mating mistakes,

I mean making, and I’m wandering

if I’ve inherited what

my father’s got.

I first understood it when he tried

to introduce me to somebunny:

“This is my doctor,” he said,

then didn’t say more, “my daughter.”

The man kindly nodded

out the door.

I thought: is this dimension

what I’m headed for?

I mean dementia.

Not Autheimer’s, but that kind he has,

possessive aphasia: oh that’s good,

I meant to say progressive.

Talk about euthanasia!

I mean euphemasia,

nice words inside your head not there,

and it’s not progress at all.

No, he’s up against the boil

after years now of a sad, slow wall

and he’s so hungry,

I mean angry.

Me too. I need to get my rhymes in

while I still mean. I mean can.3

It is rare that metaphysical wit can support a thesis about a poet’s fear of aphasia as emblematic of the larger fear of dementia that strikes us even as we live longer lives.

* * *

In 1988, when this series began, the Internet did not exist. The Berlin Wall had not yet come down. The words of the day were glasnost, perestroika, and “leveraged buyout.” No one had heard of the dot.com bubble, the iPhone, the selfie, the cloud, or Taylor Swift. Some people, not many, had heard of the maverick American inventor, Nikola Tesla. Time and Newsweek were still important, but the press was more interested in Donna Rice and Monkey Business than in Gary Hart’s foreign policy ideas, and evidence of plagiarism wiped out Joe Biden’s campaign for the presidency. Michael Jordan scored thirty-five points a game and was the NBA’s best scorer and best defender. Candice Bergen played Murphy Brown, a single mother, on television, and Kirk Gibson hit a home run more improbable than any imagined by Bernard Malamud or the creators of the 1955 musical Damn Yankees. Though the crash of October 1987 was still on people’s minds, money remained the caffeine of the ambitious. Oliver Stone’s Wall Street opened with the Twin Towers rising majestically while Frank Sinatra sang “Fly Me to the Moon.”