Space gladiators, p.1

Space Gladiators, page 1

01-10-2023

MAN AND BEAST-HUNTER AND PREY . . .

Lycon was less than a hundred yards from the hedge, when the blue-scaled killer vaulted over the thorny barrier with an acrobat’s grace. It writhed through the air, and one needle-clawed hand slashed out—tearing the throat from the nearest Molossian before the dog was fully aware of its presence. The creature bounced to the earth like a cat, as the last two snarling hounds sprang for it together. Spinning and slashing as it ducked under and away, the thing was literally a blur of motion. Deadly motion. Neither hound completed its leap, as lethal talons tore and gutted—slew with nightmarish precision.

Lycon skidded to a stop on the muddy held. He did not need to glance behind him to know he was alone with the beast. Its eyes glowed in the sunset as it turned from the butchered dogs and stared at its pursuer.

The hunter advanced his spear, making no attempt to throw. As fast as it moved, the thing would easily dodge his cast. And Lycon knew that if the beast leaped, he was dead …

—From “Killer”

by Karl Edward Wagner

and David Drake

Ace Books by David Drake

HAMMER’S SLAMMERS

KILL RATIO

(with Janet Morris)

Ace Books Edited by David Drake and Bill Fawcett

THE FLEET

THE FLEET: COUNTERATTACK

THE FLEET: BREAKTHROUGH

Ace Books Edited by Joe Haldeman with Charles G. Waugh and Martin Harry Greenberg

SPACEFIGHTER

SUPERTANKS

BODY ARMOR: 2000

EDITED BY DAVID DRAKE

WITH CHARLES C. WAUGH

AND MARTIN HARRY GREENBERG

ACE BOOKS, NEW YORK

Introduction copyright © 1989 by David Drake

“Diplomat-at-Arms” copyright © 1968 by Keith Laumer. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“In the Arena” copyright © 1963 by Brian W. Aldiss. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Kokod Warriors” copyright 1952 by Standard Magazines, Inc.; renewed © 1980 by Jack Vance. Reprinted by permission by Kirby McCauley, Ltd.

“Fiesta Brava” copyright © 1967 by Condé Nast Publications, Inc. Reprinted by permission of the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc., 845 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10022.

“Arena” copyright 1944 by Street &. Smith Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1972 by Fredric Brown. Reprinted by permission of Roberta Pryor, Inc.

“Brood World Barbarian” copyright © 1969 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Dueling Machine” copyright © 1963 by Condé Nast Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1985 by Ben Bova. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Killer” copyright © 1974 by Karl Edward Wagner and David A. Drake for Midnight Sun No. 1. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

SPACE GLADIATORS

An Ace Book / published by arrangement with

the editors

PRINTING HISTORY

Ace edition/April 1989

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1989 by Martin Harry Greenberg.

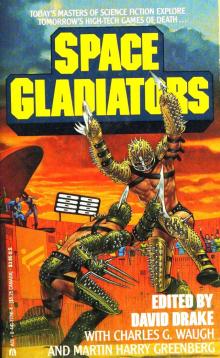

Cover art by Walter Velez.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part,

by mimeograph or any other means, without permission.

For information address: The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016.

ISBN: 0-441-77741-4

Ace Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016.

The name “ACE” and the “A” logo are trademarks belonging to

Charter Communications, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

10 9 8 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

INTRODUCTION - LET THE GAMES BEGIN…. - by David Drake

DIPLOMAT-AT-ARMS - by Keith Laumer

IN THE ARENA - by Brian W. Aldiss

THE KOKOD WARRIORS - by Jack Vance

FIESTA BRAVA - by Mack Reynolds

ARENA - by Fredric Brown

BROOD WORLD BARBARIAN - by Perry A. Chapdelaine

THE DUELING MACHINE - by Ben Bova

KILLER - by Karl Edward Wagner and David Drake

SPACE

GLADIATORS

INTRODUCTION

LET THE GAMES

BEGIN …

by David Drake

The classical world knew there were two different species of elephant, the African and the Asian. There was a general tendency to call the eastern variety ‘Syrian elephants’ rather than ‘Indian’ as we do, because Syria was the port of entry, but they were talking about the same animal.

Many Romans could tell you that the most striking difference between African and Asian elephants was that the eastern variety was much larger than its African cousin.

That isn’t how we learned it in school, because Romans knew nothing of the sub-Saharan species that we think of as African elephants. The Romans meant a northern variety inhabiting the mountains of Mauretania—very similar to the sub-Saharan species, but dwarfed in size.

Whereas we aren’t familiar with Mauretanian elephants, because they’ve been extinct since Roman times. The species was wiped out in the centuries-long slaughter of the Roman Games.

‘Games’ is a slight mistranslation of the Latin word Ludus. The Latin vocabulary is much more limited than that of English, so the same word did duty for dicing in a tavern, a performance of Sophocles—and the slaughter in the arena.

Call them entertainments, then. It’s even been suggested there was some socially-redeeming value in them. A city dweller in the Roman world had almost as good an opportunity as an avid viewer of public television today to see varied life forms.

And then watch them die. By the hundreds, by the thousands. … By the species.

A Roman also had the opportunity to watch humans slaughtered by the thousands. So far as I know, there hasn’t been an attempt to find social benefit in that, though during World War II both the Germans and the Japanese slaughtered prisoners of war in much greater numbers than the Romans managed in their arenas.

The thing is, modem Germans and Japanese made an attempt to hide what they were doing. There were a few Romans (and rather more Greeks under Roman rule) who objected to the Games on philosophical grounds; but they tended to be the folk who objected to slavery also, and slavery was the foundation of classical society. So a few otherworldly philosophers carped, but the citizenry as a whole crammed the amphitheaters.

The human victims of the arena were mostly prisoners of war and criminals (among whom Christians seeking martyrdom amounted to a significant percentage at various times). Sometimes they were armed and set against one another, but only the immediate participants had the slightest interest in who won.

Very often, the prisoners weren’t expected to fight: they only had to die. Watching unarmed humans being torn by lions ranked right up there in Roman popularity with seeing antelope shot by archers from high platforms that avoided any risk of the shooters being accidentally gored.

Mass human victims were in a class identical to that of the beasts who died in other events of the day. Professional gladiators were in quite a different category.

A top gladiator was a sports hero who could expect wealth in addition to adulation. He could expect to hobnob with the raffish members of ‘the best people’. Very occasionally, he was from a noble family himself.

He didn’t expect to die in the arena.

Oh, it could happen; the way a wide receiver can get his neck broken in a modem football game. But we have, in the form of graffiti, the Won-Lost records of enough gladiators to know that while it was a tough business, a professional gladiator wasn’t simply serving a deferred death sentence.

Gladiators weren’t at the pinnacle of their own social class. That place was filled by the charioteers, whose races were an even greater part of the classical social order than gladiatorial combats. (Juvenal’s ‘bread and circuses’ refers to chariot races, not sword-fights.)

Since the races were incredibly brutal events themselves— imagine a combination of Demo Derby and Italian-style motorcycle racing—they can be considered combat with a different style of weapon.

Gladiatorial bouts probably began as battles at funerals to achieve a religious purpose: sending the deceased off with a blood offering. Religious motives also underlie the kindred practice of Trial by Combat: the Gods know who is right, who is pure, who is fit. Let the contenders compete under controlled conditions so that the Gods can give the victory where it is due.

Historically, combat by champions hasn’t proven a very effective alternative to battle. It’s hard to convince an army to go home in defeat simply because one of its members had a bad day against the opposing champion. Indeed, even the semilegendary accounts—for which David and Goliath can stand for any number of other examples—usually end with the victor’s side butchering the army of the defeated champion.

Formal single combat was more effective when it was intended to solve some more personal matter—usually honor, though that was as likely to be ‘the honor of winning the tournament’ as anything directly involving a lady’s name. It did, after all, prove who was the better man that day, and a surviving loser had his bruises as encouragement not to pursue matters further.

If the loser didn’t survive, matters had been settled even more firmly.

Violence is a terrible intrusion in

An interesting arena, if you’ll permit me.

The stories we’ve chosen here explore a number of the aspects of the subject in the context of science fiction. As you go through them, consider the continuum of peace; gladiatorial games; war; and the utter chaos toward which war always tends.

I’d like to live in a world at peace.

But I might settle for a world in which the bloodiest slaughter could be covered as sports news, rather than international affairs.

DIPLOMAT-AT-ARMS

by Keith Laumer

The cold white sun of Northroyal glared on pale dust and vivid colors in the narrow raucous street. Retief rode slowly, unconscious of the huckster’s shouts, the kaleidoscope of smells, the noisy milling crowd. His thoughts were on events of long ago on distant worlds; thoughts that set his features in narrow-eyed grimness. His bony, powerful horse, unguided, picked his way carefully, with flaring nostrils, wary eyes alert in the turmoil.

The mount sidestepped a darting gamin and Retief leaned forward, patted the sleek neck. The job had some compensations, he thought; it was good to sit on a fine horse again, to shed the gray business suit—

A dirty-faced man pushed a fruit cart almost under the animal’s head; the horse shied, knocked over the cart. At once a muttering crowd began to gather around the heavy-shouldered gray-haired man. He reined in and sat scowling, an ancient brown cape over his shoulders, a covered buckler slung at the side of the worn saddle, a scarred silver-worked claymore strapped across his back in the old cavalier fashion.

Retief hadn’t liked this job when he had first heard of it. He had gone alone on madman’s errands before, but that had been long ago—a phase of his career that should have been finished.

And the information he had turned up in his background research had broken his professional detachment. Now the locals were trying an old tourist game on him; ease the outlander into a spot, then demand money… .

Well, Retief thought, this was as good a time as any to start playing the role; there was a hell of a lot here in the quaint city of Fragonard that needed straightening out.

“Make way, you rabble!” he roared suddenly. “Or by the chains of the sea-god I’ll make a path through you!” He spurred the horse; neck arching, the mount stepped daintily forward.

The crowd made way reluctantly before him. “Pay for the merchandise you’ve destroyed,” called a voice.

“Let peddlers keep a wary eye for their betters,” snorted the man loudly, his eye roving over the faces before him. A tall fellow with long yellow hair stepped squarely into his path.

“There are no rabble or peddlers here,” he said angrily. “Only true cavaliers of the Clan Imperial. …”

The mounted man leaned from his saddle to stare into the eyes of the other. His seamed brown face radiated scorn. “When did a true Cavalier turn to commerce? If you were trained to the Code you’d know a gentleman doesn’t soil his hands with penny-grubbing, and that the Emperor’s highroad belongs to the mounted knight. So clear your rubbish out of my path, if you’d save it.”

“Climb down off that nag,” shouted the tall young man, reaching for the bridle. “I’ll show you some practical knowledge of the Code. I challenge you to stand and defend yourself.”

In an instant the thick barrel of an antique Imperial Guards power gun was in the gray-haired man’s hand. He leaned negligently on the high pommel of his saddle with his left elbow, the pistol laid across his forearm pointing unwaveringly at the man before him.

The hard old face smiled grimly. “I don’t soil my hands in street brawling with new-hatched nobodies,” he said. He nodded toward the arch spanning the street ahead. “Follow me through the arch, if you call yourself a man and a Cavalier.” He moved on then; no one hindered him. He rode in silence through the crowd, pulled up at the gate barring the street. This would be the first real test of his cover identity. The papers which had gotten him through Customs and Immigration at Fragonard Spaceport the day before had been burned along with the civilian clothes. From here on he’d be getting by on the uniform and a cast-iron nerve.

A purse-mouthed fellow wearing the uniform of a Lieutenant-Ensign in the Household Escort Regiment looked him over, squinted his eyes, smiled sourly.

“What can I do for you, Uncle?” He spoke carelessly, leaning against the engraved buttress mounting the wrought-iron gate. Yellow and green sunlight filtered down through the leaves of the giant linden trees bordering the cobbled street.

The gray-haired man stared down at him. “The first thing you can do, Lieutenant-Ensign,” he said in a voice of cold steel, “is come to a position of attention.”

The thin man straightened, frowning. “What’s that?” His expression hardened. “Get down off that beast and let’s have a look at your papers—if you’ve got any.”

The mounted man didn’t move. “I’m making allowances for the fact that your regiment is made of up idlers who’ve never learned to soldier,” he said quietly. “But having had your attention called to it, even you should recognize the insignia of a Battle Commander.”

The officer stared, glancing over the drab figure of the old man. Then he saw the tarnished gold thread worked into the design of a dragon rampant, almost invisible against the faded color of the heavy velvet cape.

He licked his lips, cleared his throat, hesitated. What in name of the Tormented One would a top-ranking battle officer be doing on this thin old horse, dressed in plain worn clothing? “Let me see your papers—Commander,” he said.

The Commander flipped back the cape to expose the ornate butt of the power pistol.

“Here are my credentials,” he said. “Open the gate.”

“Here,” the Ensign spluttered, “What’s this …”

“For a man who’s taken the Emperor’s commission,” the old man said, “you’re criminally ignorant of the courtesies due a general officer. Open the gate or I’ll blow it open. You’ll not deny the way to an Imperial battle officer.” He drew the pistol.

The Ensign gulped, thought fleetingly of sounding the alarm signal, of insisting on seeing papers … then as the pistol came up, he closed the switch, and the gate swung open. The heavy hooves of the gaunt horse clattered past him; he caught a glimpse of a small brand on the lean flank. Then he was staring after the retreating back of the terrible old man. Battle Commander indeed! The old fool was wearing a fortune in valuable antiques, and the animal bore the brand of a thoroughbred battle-horse. He’d better report this. … He picked up the communicator, as a tall young man with an angry face came up to the gate.

Retief rode slowly down the narrow street lined with the stalls of suttlers, metalsmiths, weapons technicians, free-lance squires. The first obstacle was behind him. He hadn’t played it very suavely, but he had been in no mood for bandying words. He had been angry ever since he had started this job; and that, he told himself, wouldn’t do. He was beginning to regret his highhandedness with the crowd outside the gate. He should save the temper for those responsible, not the bystanders; and in any event, an agent of the Corps should stay cool at all times. That was essentially the same criticism that Magnan had handed him along with the assignment, three months ago.