The making of middle ear.., p.1

The Making of Middle-Earth, page 1

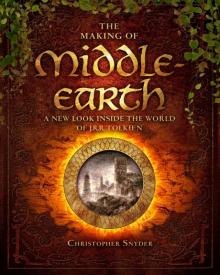

Frontispiece: A ca. 1890 photochrom of Magdalen College, Oxford, where J. R. R. Tolkien and his fellow Inklings would meet on Thursday evenings.

THE

MAKING OF

Middle-earth

A NEW LOOK INSIDE THE WORLD OF J.R.R. TOLKIEN

CHRISTOPHER SNYDER

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

© 2013 by Christopher Snyder For photographic copyright information, please see picture credits at the end of the book.

Produced by Laurie Dolphin for Authorscape, Inc. Interior design by Amy Wahlfield

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4027-9222-9

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com.

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

www.sterlingpublishing.com

Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company:

Excerpts from THE HOBBIT by J.R.R. Tolkien. Copyright © 1937 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd. Copyright © 1966 by J.R.R. Tolkien. Copyright © Renewed 1994 by Christopher R. Tolkien, John F.R. Tolkien and Priscilla M.A.R. Tolkien. Copyright © Restored 1996 by the Estate of J.R.R. Tolkien, assigned 1997 to the J.R.R. Tolkien Copyright Trust.

Excerpts from THE LORD OF THE RINGS by J.R.R. Tolkien. Copyright © 1954, 1955, 1965, 1966 by J.R.R. Tolkien. Copyright © Renewed 1982, 1983 by Christopher R. Tolkien, Michael H.R. Tolkien, John F.R. Tolkien, and Priscilla M.A.R. Tolkien. Copyright © Renewed 1993, 1994 by Christopher R. Tolkien, Michael H.R. Tolkien, John F.R. Tolkien, and Priscilla M.A.R. Tolkien.

Excerpts from THE SILMARILLION, Second Edition by J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien. Copyright © 1977 by The J.R.R. Tolkien Copyright Trust and Christopher Reuel Tolkien. Copyright © 1981 by The J.R.R. Tolkien Copyright Trust. Copyright © 1999 by Christopher Reuel Tolkien.

Excerpts from “On Fairy-Stories” from TREE AND LEAF by J.R.R. Tolkien. Copyright © 1964 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd. Copyright © Renewed 1992 by John F.R. Tolkien, Christopher R. Tolkien, and Priscilla M.A.R. Tolkien. Copyright © 1988 by The Tolkien Trust.

Excerpts from “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” from SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT, PEARL AND SIR ORFEO, translated by J.R.R. Tolkien. Copyright © 1975 by The J.R.R. Tolkien Copyright Trust. Copyright © 1975 by Christopher Reuel Tolkien,

Excerpts from “English and Welsh” and “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” from THE MONSTERS AND THE CRITICS AND OTHER ESSAYS by J.R.R. Tolkien. Copyright © 1983 by Frank Richard Williamson and Christopher Reuel Tolkien as Executors of the Estate of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Excerpts from THE CHILDREN OF HURIN by J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien. Copyright © 2007 by the J.R.R. Tolkien Copyright Trust and Christopher Reuel Tolkien

Excerpts from THE LETTERS OF J.R.R. TOLKIEN, edited by Humphrey Carpenter with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien. Copyright © 1981 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd.

All rights reserved

J.R.R. Tolkien excerpts reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers (UK) © The Trustees of The J.R.R. Tolkien 1967 Settlement 1954, 1955, 1966

C.S. Lewis: The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature; An Experiment in Criticism; and Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature © Cambridge University Press 1964; 1961; and 1966 and 1998 respectively.

Quotes by C.S. Lewis in Humphrey Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, Copyright © 1977, 1978, 1987 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd.

C.S. Lewis excerpts reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company (US) and HarperCollins Publishers (US and UK). All rights reserved: All My Road Before Me: The Diary of C.S. Lewis 1922–1927, Copyright © 1991 C.S. Lewis Pte. Ltd.; The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, Copyright © 1952 by C.S. Lewis Pte. Ltd, © renewed 1980; Surprised by Joy, Copyright © 1955 by C.S. Lewis Pte. Ltd; The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, vol II, ed. by Walter Hooper, Copyright © 2004 C.S. Lewis Pte. Ltd; The Complete C. S. Lewis Signature Classics, Copyright © 2002 C.S. Lewis Pte. Ltd; Letters of C.S. Lewis, revised ed., ed. by Walter Hooper, Copyright © 1966 by W.H. Lewis; Copyright © 1966, 1988 by C.S. Lewis Pte. Ltd.

“The making of things is in my heart from my own making by Thee.”1

—J. R. R. TOLKIEN, THE SILMARILLION, “OF AULË AND YAVANNA,” 1977

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PREFACE

1: LEARNING HIS CRAFT

From Africa to Birmingham

Oxford

The Great War

Tolkien the Scholar

Tolkien the Teacher

The Inklings

Fame and Retirement

Writing Tolkien

2: TOLKIEN’s MIDDLE AGES

Back to the Sources

Ancient Greece and Rome

Celtic Britain and Ireland

The Anglo-Saxons and Old English

The Vikings and Old Norse

Middle English Literature

King Arthur and the Matter of Britain

Victorian Fairy Tales and the Gothic Revival

Finnish and The Kalevala

William Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites

Andrew Lang

George MacDonald

The Northern Land

3: “THERE AND BACK AGAIN”

Hobbits and Dwarves

Trolls and Goblins, Gnomes and Elves

Mountains, Rings, and Riddles in the Dark

Beorn

Mirkwood and Lake-town

Smaug

Endings

4: TALES OF THE THIRD AGE

The Fellowship of the Ring

The Two Towers

The Return of the King

5: THE SONG OF ILÚVATAR

The Silmarillion

The Children of Húrin

Appendix I:

MONSTERS AND CRITICS

Appendix II:

MEDIA AND MIDDLE-EARTH

Appendix III:

TOLKIENIANA

Appendix IV:

THE MORAL VIRTUES OF MIDDLE EARTH

A TOLKIEN TIMELINE

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND TOLKIEN RESOURCES

PICTURE CREDITS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Unlike most medievalists I have met, I did not have an appreciation for Tolkien as a young reader. I fell in love with the Arthurian legends as a teenager, became a professional historian, and only discovered the genius of Tolkien later in life. I owe a debt to all the Tolkien enthusiasts I have met during these years; to Peter Jackson, for kindling the flames; and to my Oxford Honors students for helping me focus my thoughts for this book. Special thanks are due to the staff of the Bodleian Library, the University of Oxford; the Emerson G. Reinsch Library, Marymount University; the Mitchell Memorial Library, Mississippi State University; and to Tom Shippey and Walter Hooper, for their help and encouragement.

This book in its final form would not have been a reality without the efforts of Joelle Delbourgo, my agent; Barbara Berger, my diligent and enthusiastic editor at Sterling Publishing; and the Tolkien Estate and publishers, with special thanks to Cathleen Blackburn and Stuart Patterson. Illustrated books like this one are a team effort, and the bulk of the work in this area was done by Sterling’s Michael Fragnito, Editorial Director; Elizabeth Mihaltse, Art Director, Trade Covers; Chris Thompson, Art Director; Rodman Neumann, Managing Editor; and Elana Mitchel, Manager, Digital Asset Services; with assistance from packager Laurie Dolphin at Authorscape, interior designer Amy Wahlfield, and cover designer the BookDesigners.

Lastly, I thank my daughter Carys for reading Tolkien (and watching the films) with me, and give my love to my wife Renée for never complaining about this newest obsession. And Professor Tolkien, in caelum observans, I beg your forgiveness for all errors herein.

PREFACE

“The world has changed. I feel it in the water. I feel it in the earth. I smell it in the air. Much that once was is lost, for none now live who remember it.”2

—GALADRIEL [CATE BLANCHETT] IN THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING, THE MOVIE, 2001

MANY WHO HAVE READ the fictional works of J. R. R. Tolkien, or who have seen the trilogy of films made by Peter Jackson, would agree with the above sentiment of Galadriel. After our first encounter with Middleearth, our world does not quite feel the same. We cannot look at gently rolling hills without thinking of the Shire, cannot watch autumn leaves turning gold without recalling Lothlorien, while the call of seagulls over the waves carries our spirits “into the West.” Indeed, how many of us have looked hard into a mighty tree hoping to find the eyes of Treebeard peering out at us.

Tolkien’s Middle-earth seems at first to be an utterly new and exciting creation. But on closer inspection, it is a very old world and dimly recognizable. Professor Tolkien—like his friend and colleague C. S. Lewis—was one living among us who did remember it. To be more accurate, he recognized this world in the languages, myths, and history of ancient and medieval Europe. Captivated as a child by what he later called “fairy stories,” he became a professional medievalist and devote

There seems to be at least three worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien. There is the physical world in which he was born and educated, and in which he taught, wrote, made friendships, worshipped, and raised a family. These experiences—and places like Birmingham and Oxford—had an enormous impact on Tolkien the person as well as Tolkien the writer. The second world is the intellectual realm where Tolkien spent much of his time, beginning with his first fascination with fairy tales through his adult obsessions with Northern languages and legends. This is the world of Beowulf and Brunhild, of Gawain and Fafnir, and the power and beauty of this world emanates from the very names of its places: Avalon, Heorot, Valhalla. Lastly, there is the world most familiar to Tolkien fans: Middle-earth, a land of elves and dark powers and Tom Bombadil. All three worlds will be discussed in this book, along with a fourth of which Tolkien had only a glimpse before he died: that of Tolkieniana, of fandom and franchise, culminating (as of this writing) in three of the most successful movies ever made.

Water, earth, and sky: a bucolic scene photographed ca. 1890, in Devon, England, where Tolkien visited as a boy.

FOR A LONG TIME THERE WAS ONLY ONE significant biography of J. R. R. Tolkien. It was written by Humphrey Carpenter in 1977 and based, in part, on interviews he conducted with Tolkien and his family and friends.5 This biography is a companion and very similar in approach to Carpenter’s The Inklings (1978), which deals with Tolkien alongside other members of his Oxfordian circle, especially the writers C. S. Lewis and Charles Williams. Carpenter felt that Tolkien deserved separate treatment, but wisely sought to publish the biography only after Tolkien’s death, for Tolkien was not at all fond of the genre. Carpenter’s biography has never been surpassed, though now it should be supplemented by the published letters of Tolkien, the recently discovered war record given full treatment by John Garth, and the invaluable two-volume reference work by Christina Scull and Wayne Hammond. Tom Shippey succeeds admirably in peering into the “inner life” of Tolkien the Philologist—philology, now called historical linguistics—being both Tolkien’s passion and his profession, as it is for Shippey as well).6 But the handful of competing biographies, many of which appeared around the time of Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films, reveal little more than what Carpenter, Shippey, Garth, and Tolkien himself have provided us.7

Conversely, literary criticism of at least Tolkien’s major works has never been lacking. As the modern literary genre of fantasy—virtually invented by Tolkien—has matured in the second half of the twentieth century, many academics have turned to serious and scholarly discussion of its major works. Those who have specialized in Tolkien studies (see Appendix I) have been aided in recent years by the publication of annotated scholarly editions of both The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1954–55) as well as the History of Middle-earth series (1983–96), edited by Christopher Tolkien, which traces the permutations of The Lord of the Rings and the “legendarium” (i.e., The Silmarillion and related stories of Middle-earth legends). The release of new Tolkien material, such as The Children of Húrin (2007) and The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún (2009), provides yet more discussion for fans and critics alike.8

A few recent books have attempted to look at the whole Tolkien phenomenon, or at least at the varying reception of Tolkien’s fictional works over the last few decades and of Jackson’s films.9 With the release of the three Hobbit films in 2012, 2013, and 2014, the name J. R. R. Tolkien may then be associated with one of the most successful film franchises in the history of cinema (alongside Harry Potter, James Bond, and Star Wars). Since Tolkien was overwhelmingly critical of an attempted animated version of the Lord of the Rings (he read the script in 1957–58) and thought that a live-action version could never be accomplished, one can only imagine his astonishment at the fact that his invented world is now equally as well known from cinematic images as it is from books.

Still, despite the continuing popularity of Tolkien’s books and the flurry of attention surrounding the Jackson films, no one book has attempted to connect these modern literary and cinematic threads with the Middle-earth that Tolkien knew first, the one he found in the ancient languages and poetry of northwestern Europe. Long have we known the influence of works like Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight upon Tolkien’s fiction, but what of the historical cultures from whence these came? Historians and archeologists have, since the publication of The Lord of the Rings, revealed much about the cultures of the Celts, the Anglo-Saxons, and the Norse in the late Iron Age and the early Middle Ages. Tolkien himself embarked on such pursuits through his academic publications, seldom read by the fans of his fiction. The Making of Middle Earth will attempt to place Tolkien’s scholarship and his fiction within the context of his wider pursuit of knowledge about the early inhabitants of the British Isles and of the remote Germanic-speaking realms on the Continent. Both the material and the literary cultures of these ancient peoples can help us to have a deeper appreciation of Tolkien’s books and even their recent film and gaming adaptations.

In a famous 1936 essay, Professor Tolkien once excoriated historians for dismantling the masterful poem Beowulf in search of mundane clues about Anglo-Saxon society.10 Let this book serve as an apology—not an apologia—from one historian who tries not to knock over towers in order to understand how they are built. In recent years archaeologists and historians have uncovered a few monuments that might even have prompted the professor to remove his ever-present pipe—if just for a moment—and take notice of the boldness and beauty, of the craft and ingenuity of his beloved Northern peoples.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, ca. 1955.

1

Learning His Craft

FROM AFRICA TO BIRMINGHAM

JOHN RONALD REUEL TOLKIEN was born on January 3, 1892, in Bloemfontein, the capital of the Orange Free State, which was later incorporated into South Africa. His parents were Arthur Reuel Tolkien and Mabel Suffield, who had come to southern Africa a year earlier and were married in Cape Town. Mabel gave birth to two sons there, John Ronald (later known to his friends as Ronald) and Hilary. Arthur Tolkien, a bank manager, was the descendant of German immigrants who had come to England in the eighteenth century. His eldest son later took a linguistic interest in the family name, Tolkiehn, with its origins in Old Saxony, birthplace of “that noble northern spirit, a supreme contribution to Europe.”1 But two wars against Germany—and the virulent anti-Semitism of the Nazi period—somewhat tempered Ronald’s pride in his German roots.2

Ronald Tolkien had a far greater interest in his mother’s family, the Suffields, whose origins he believed lay in the Anglo-Saxon West Midlands county. “Though a Tolkien by name, I am a Suffield by tastes, talents, and upbringing, and any corner of that country [Worcestershire] (however fair or squalid) is in an indefinable way ‘home’ to me, as no other part of the world is.”3 It became literally home to him when, suffering from the torrid South African climate, Mabel moved back to the West Midlands, bringing Ronald and Hilary with her to live in Birmingham in 1895. Though meant to be a temporary move, it became permanent when the tragic news of Arthur Tolkien’s death from rheumatic fever reached his family in February 1896.

Mabel Tolkien sent this hand-colored Christmas card from South Africa to her family, the Suffields, in Birmingham, in 1892. A nurse holds baby Ronald, then ten months old. Their cook and a servant pose with the Tolkiens.