City of last chances, p.1

City of Last Chances, page 1

CITY

OF

LAST

CHANCES

ALSO BY ADRIAN TCHAIKOVSKY

SHADOWS OF THE APT

Empire in Black and Gold

Dragonfly Falling

Blood of the Mantis

Salute the Dark

The Scarab Path

The Sea Watch

Heirs of the Blade

The Air War

War Master’s Gate

Seal of the Worm

TALES OF THE APT

Spoils of War

A Time for Grief

For Love of Distant Shores

The Scent of Tears (with Frances Hardinge et al.)

ECHOES OF THE FALL

The Tiger and the Wolf

The Bear and the Serpent

The Hyena and the Hawk

CHILDREN OF TIME

Children of Time

Children of Ruin

Children of Memory

DOGS OF WAR

Dogs of War

Bear Head

OTHER FICTION

Guns of the Dawn

Spiderlight

Ironclads

Cage of Souls

Firewalkers

The Doors of Eden

Feast and Famine

(collection)

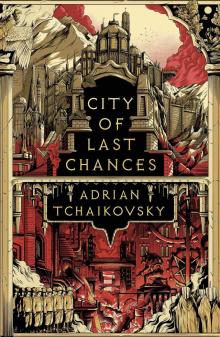

CITY

OF

LAST

CHANCES

ADRIAN

TCHAIKOVSKY

www.headofzeus.com

First published in the UK in 2022 by Head of Zeus Ltd,

part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright © Adrian Tchaikovsky, 2022

The moral right of Adrian Tchaikovsky to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB): 9781801108423

ISBN (XTPB): 9781801108430

ISBN (E): 9781801108454

Map © Joe Wilson

First Floor East

5–8 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

WWW.HEADOFZEUS.COM

Contents

Also by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Title Page

Copyright

Factions

Dramatis Personae

Map of Ilmar

Yasnic’s Relationship with God

The Final Moments of Sage-Archivist Ochelby

A Game of Chaq

Ruslav in Love Again

Blackmane’s New Collar

The Old Songs

Parliament of Fowls

Maestro in Durance

Mother Guame’s Interrogation

Mosaic: City of Last Chances

The Reproach of Statlos Shrievsby

The Pawnbroker

The Face of Perfection

Ruslav’s Master’s Voice

Jem’s Reasons for Leaving

Unleashing Hell

Mosaic: The Hospitality of the Varatsins

Ruslav in the Teeth

Nihilostes Loses a Convert

Going Home

Chains

Not Venom but Eggs

Conversations About God

Breaking Things

The Second Murder

Dancing on Air

Through the Bottom of a Bottle

Orvechin’s Boots

The Price of Rope

Evidence

The Day Gets Only Worse

Mosaic: Wings

Drinking Alone

The Bitter Sisters

Past the Threshold

Blackmane’s Reckoning

Mosaic: The Spark

Fire

Mosaic: The Dousing

Higher Powers

The Apostate

Hellgram’s War

The Fine Print

Unity and Division

Port to Nowhere

A Single Piece of Bronze

Mosaic: Resurrections

Mentioned in Reports

Another Round

Acknowledgements

About the Author

An Invitation from the Publisher

FACTIONS OF THE CITY OF ILMAR

Allorwen – from the nation of Allor

Armigers – the aristocratic families of Ilmar

Divinati – from the nation of the Divinates

Gownhall – the Ilmari university

Herons – resistance faction of the riverfolk

Indwellers – the people of the Anchorwood

Lodges – criminal gangs

Loruthi – from the nation of Lor

Ravens – resistance faction of the Armiger families

Shrikes – murderers for the resistance

Siblingries – workers’ organisations

Vultures – resistance faction of the Ilmar streets

FACTIONS OF THE PALLESEEN OCCUPATION

Temporary Commission of Ends and Means – the ruling body of Pallesand

Palleseen Sway – the occupied territories as a whole

Perfecture – an individual occupied territory

School of Correct Erudition (Archivists) – responsible for learning and magic

School of Correct Appreciation (Invigilators) – responsible for art and the judiciary

School of Correct Exchange (Brokers) – responsible for trade

School of Correct Conduct (Monitors) – responsible for military and enforcement

School of Correct Speech (Inquirers) – responsible for religion, language and espionage

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Aullaime – Allorwen conjurer with the Siblingries

Benno – Vulture thug

Blackmane – Allorwen pawnbroker

Fellow-Monitor Brockelsby – Correct Conduct

Carelia – one half of the Bitter Sisters, Vulture leader

Cheryn – Vulture thug

Sage-Invigilator Culvern – Perfector of Ilmar, Correct Appreciation

Dorae – Allorwen antiques dealer

Dostritsyn – ruin-diver

Mother Ellaime – Allorwen landlady

Emlar – student

Ergice – Vulture thug

Companion-Monitor Estern – Correct Conduct

Evene – the other half of the Bitter Sisters, Vulture leader

Fleance – Heron gambler

Fyon – Shrike murderer

Archivist Gadders – Correct Erudition

God – divine entity

Maestra Gowdi – Gownhall master

Grymme – ruin-diver

Mother Guame – Allorwen brothel-keeper

Fellow-Inquirer Hegelsy – Correct Speech

Hellgram – bouncer at the Anchorage, foreigner

Hervenya – student

Hoyst – hangman

Jem – Divinati bartender at the Anchorage

Kosha – priest, Yasnic’s master, dead

Langrice – keeper of the Anchorage

Lemya – student

Petric Lesselkin – Siblingry scrapherd

Meraqui – ruin-diver

Companion-Archivist Nasely – Correct Erudition

Nihilostes – priestess of the divine scorpionfly

Fellow-Broker Nisbet – Correct Exchange

Sage-Archivist Ochelby – Correct Erudition

Father Orvechin – Siblingry leader

Orvost, the Divine Bull – divine entity

Maestro Ivarn Ostravar – Gownhall master

Maestro Porvilleau – Allorwen Gownhall master

Archivist Riechy – Correct Erudition

Ruslav – Vulture thug

Statlos Shrievsby – officer, Correct Conduct

Sachemel Sirovar – former head of the family, dead

Shantrov Sirovar – Armiger and student

Vidsya Sirovar – Armiger and Raven

Fellow-Invigilator Temsel – Correct Appreciation

Tobriant – Allorwen furniture maker

Johanger Tulmueric – Loruthi merchant

Maestro Vorkovin – Gownhall master

Yasnic – priest

Zenotheus, Scorpionfly God of Chaos – divine entity

Map of Ilmar

Yasnic’s Relationship with God

Yasnic the priest. Thin and not young, though not quite old. Half lost in clothes tailored for a larger man in the voluminous Ilmari style. Face hollow, hair greying before it should, thinning, creeping back from his temples like an army that, seeing its opposition is time, no longer has the will to fight…

That morning, God was complaining again. Yasnic lay crunched up in bed, knees almost to his chin and his feet twined together. Trying to tell from the way the light filtered in through the filthy window whether the frost was just on the outside, or on the inside again. He could have put a hand out to touch the panes and check. He could have put a foot out and kicked out at God. Or the far wall. It was, he decided, a blessing. A small room held his body heat longer. If he’d been able to afford anything larger, the

“It’s cold,” God said. “It’s so cold.” The divine presence was curled up on His shelf like an emaciated cat, and about the same size. He had shrunk since the night before, and perhaps that, too, was a blessing. Sometimes Yasnic could do with a little less God in his life, and here he was this morning, and God was smaller by at least a quarter. He gave thanks, his knee-jerk reaction ingrained from long years of good upbringing from Kosha, the previous priest of God. Back when Ilmar had been a more tolerant place, and old Kosha and Yasnic and God had lived in three rooms above a tanner’s and had meat at least once a twelveday.

Not a twelveday, he reminded himself. The School of Correct Exchange was levying fines and making arrests for people using the old calendar, he’d heard. He had to start thinking in terms of a seven-day week, except then he couldn’t look back on the way things had been and quantify the time properly. How often had they had meat, back when he’d been a boy learning at Kosha’s knee? What was seven into twelve or twelve into seven or however it might work? His mathematics weren’t good enough to work it out. And so, obscurely, it felt as though a swathe of his memories was locked away by the new ordnances. Also, he’d just given thanks to God that he had less God in his life, and God, the recipient of those thanks, was right there and staring at him accusingly.

“I need a blanket,” said God. “It’s only the beginning of winter, and it’s so cold.”

God looked all skin and bones. He wore rags. It was only a season since Yasnic had sacrificed a good shirt to God, but the diminished state of the faith – meaning Yasnic – tended to mean anything God got His hands on didn’t last. A blanket would go the same way.

“I only have one blanket,” Yasnic told God.

“Get another one.” God stared at His sole priest from His place on the shelf up by the low ceiling. His spidery hands were gripping the edge, His nose and wisps of beard projecting over them. His skin was wrinkled and greyish, hollowed until the shape of His bones could be seen quite clearly. “In the old days I had robes of fur and velvet, and my acolytes burned sandalwood—”

“Yes, yes, I know.” Yasnic cut God off. “I only have this blanket.” He lifted the threadbare covering and regretted it instantly, the chill of the morning taking up residence in a bed with room only for one. “I suppose I’m getting up now,” he added pettily.

“Please,” said God. Yasnic stopped halfway through forcing numb feet into his overtrousers. God looked in a bad way, he had to admit. It was easy just to think that God was being selfish. God had, after all, been very used to people doing what He said and giving Him all good things, back in the day. Back in a day long before Yasnic, last priest of God, had come along. Their religion had been dying for over a century, ever since the big Mahanic Temple had been raised. And yes, Mahanism had actively spoken against other religions, but more, they’d just… expanded to fill all the available faith. People went where the social capital was. And now, under the Occupation, there really were people purging religions. Making arrests for Incorrect Speech. Just as well it’s only me and God, Yasnic thought. Easier to go unnoticed.

“Ask the woman,” God said. “Ask her for another blanket. I’m cold.”

“Mother Ellaime will not give us another blanket,” Yasnic said. In fact, their landlady would more likely want to ask about last twelved—last week’s rent. And that was another thing, of course. Since the Occupation, everything had to be paid sooner, because of the weeks. And he couldn’t quite make the maths work, but it seemed he was paying more each day of the seven than he had each day of the twelve. And it wasn’t as though being the sole surviving holy man of God actually brought in much. There were few perks and no regular take-home wage. And, under the Occupation, begging meant risking arrest for Incorrect Exchange.

“I’ll see what I can do.” Clothes on, he shambled out of the room and went down for tea. One thing Mother Ellaime did provide her boarders with was a constantly churning samovar by the fire, and both fire and tea were just about enough to set up Yasnic for a day’s scrounging.

God hadn’t been with him on the stairs but was sitting beside the samovar down in the common room. Yasnic took down a cup from its hook and filled it with dark green, steaming liquid. He wanted to avoid Mother Ellaime’s notice as he jostled elbows with his fellow boarders to get space at the single table. God was there, though. God was hunched cross-legged on the tin plate Yasnic’s neighbour had eaten porridge off.

“Ask her,” God insisted.

“I won’t do it,” murmured Yasnic. His neighbour, the big man named Ruslav who never seemed to have a job but always seemed to have money, stared at him. He couldn’t see God sitting in the remains of his porridge. He probably thought Yasnic wanted to lick his plate clean. Jealously, he pulled it closer to himself, making God scrabble for balance. Yasnic winced, aware that everyone was looking at him now, even the student girl who’d turned up a tw—two weeks ago, and whom he dreaded talking to. She was very clever, and Gownhall people loved to argue metaphysics. He was afraid he’d listen to her tortuous logic too much and then look around for God, only to find God wasn’t there anymore. And he was afraid of what he might feel, if that were ever the case.

“Ask,” God insisted peevishly. “I command it.”

“Mother,” Yasnic said. “I don’t suppose I could beg another blanket from you?” Loud enough to carry to the old woman. Aware that his quiet words were expanding to fill the room. Feeling the student’s judging eyes on him. Feeling ashamed. And it wasn’t even a useful shame, the sort that earned you credit with God or, in this case, got you a blanket, because Mother Ellaime was already shaking her head. And if there was a little more money, there might be another blanket. And likely that would mean someone at the table, who had a little less money, would be missing a blanket, because it was a closed blanket economy here at Mother Ellaime’s boarding house. And if it had just been Yasnic, he would have accepted the lack of a blanket and known that he was making someone else’s life better, and tried to warm himself with that. But it was God, and God was old and petty and selfish, but God was also cold, and Yasnic had given himself into God’s service. And so he begged Mother Ellaime, with the whole table listening archly to every word. With Ruslav, who probably had two blankets or even three, snickering in his ear. God was cold, and God didn’t have anyone else. And it was all for nothing because there wasn’t another blanket to be had, not without money he didn’t possess.

*

When darkness and the cold at last drove him back to the boarding house that night, he still didn’t possess the money. He’d tried to find work, because he could translate two dead languages, he could teach, he could sing, and even though he was a priest, he could also lift and carry and scrub. Nobody wanted him to do any of those things, or at least not if it meant giving him any money. He mostly begged, but nobody wanted to give him money for that, either.

The common room seemed swelteringly hot as he came in, the fire banked profligately high, so that he was loosening his collars immediately and shrugging out of his shapeless, too-big coat. God was waiting for him by the samovar. Even smaller, of a size to fit into the teacup Yasnic reached down. He found barely half a cup left in the urn. The discovery felt like a blow. It had never happened before. Mother Ellaime treated her tea-making responsibilities with considerably more fervour than he treated his duty to God, and that was with God actually sharing a room with him.

“Ah…” Hearing his own voice, thin and cracked.

The room was oddly quiet. He hadn’t actually registered its contents, save for God – whom he could always see clearly – and the samovar, which he had found by long familiarity and the smell of roasting tea. He had the sense of more people than usual present, and a peculiarly pregnant silence as of all of them staring at him. He rubbed at his eyes and squinted, mole-like.

The front room of Mother Ellaime’s boarding house was filled with Palleseen soldiers. Or, if not filled, they had all the seats around the single table, and they had all the tea.

The old woman herself was waiting on them. She’d pulled her shawl close around her to hide the little beaded choker she had about her neck. Not because they might steal it – though they might, glossing the act with the word ‘confiscate’. But because it would tell them she wasn’t native Ilmari, and though the Occupiers weren’t exactly kind towards the locals, they could be a great deal worse if you were from over the border in Allor.