Journal of the plague ye.., p.1

Journal of the Plague Year, page 1

An Abaddon Books™ Publication

www.abaddonbooks.com

abaddon@rebellion.co.uk

First published 2014 by Abaddon Books™, Rebellion Intellectual Property Limited, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford, OX2 0ES, UK.

Editor-in Chief: Jonathan Oliver

Commissioning Editor: David Moore

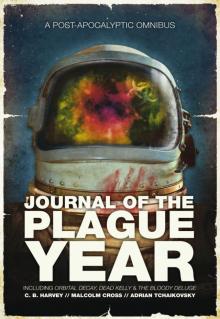

Cover Art: Sam Gretton

Design: Simon Parr & Sam Gretton

Marketing and PR: Lydia Gittins

Publishing Manager: Ben Smith

Creative Director and CEO: Jason Kingsley

Chief Technical Officer: Chris Kingsley

The Afterblight Chronicles™ created by Simon Spurrier & Andy Boot

Orbital Decay Copyright © 2014 Rebellion.

Dead Kelly Copyright © 2014 Rebellion.

The Bloody Deluge Copyright © 2014 Rebellion.

All rights reserved.

The Afterblight Chronicles™, Abaddon Books and Abaddon Books logo are trademarks owned or used exclusively by Rebellion Intellectual Property Limited. The trademarks have been registered or protection sought in all member states of the European Union and other countries around the world. All right reserved.

ISBN (epub): 978-1-84997-682-4

ISBN (mobi): 978-1-84997-683-1

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

The Afterblight Chronicles Series

Novels

The Culled by Simon Spurrier

Kill Or Cure by Rebecca Levene

Dawn Over Doomsday by Jasper Bark

Death Got No Mercy by Al Ewing

Blood Ocean by Weston Ochse

Arrowhead by Paul Kane

Broken Arrow by Paul Kane

Arrowland by Paul Kane

School’s Out by Scott K Andrews

Operation Motherland by Scott K Andrews

Children’s Crusade by Scott K Andrews

Novellas

Orbital Decay by Malcolm Cross

Dead Kelly by CB Harvey

The Bloody Deluge by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Omnibus Editions

The Afterblight Chronicles: America,

collecting The Culled, Kill or Cure and Death Got No Mercy

School’s Out Forever,

collecting School’s Out, Operation Motherland and Children’s Crusade

with bonus content

Hooded Man,

collecting Arrowhead, Broken Arrow and Arrowland

with bonus content

Journal of the Plague Year,

collecting Orbital Decay, Dead Kelly and The Bloody Deluge

CONTENTS

Introduction, by David Thomas Moore

Orbital Decay, by Malcolm Cross

Dead Kelly, by CB Harvey

The Bloody Deluge, by Adrian Tchaikovsky

The Afterblight Chronicles Chronology

Also from Abaddon Books

INTRODUCTION

It was about the beginning of September, 1664, that I, among the rest of my neighbours, heard in ordinary discourse that the plague was returned again... it was brought, some said from Italy, others from the Levant... others said it was brought from Candia; others from Cyprus. It mattered not from whence it came; but all agreed it was come again.

—Daniel DeFoe, The Journal of the Plague Year

IT’S HARD TO imagine, in our pampered world of antibiotics, vaccinations and modern hygiene, how terrifying plague must have been, in years long past. How unstoppable and overwhelming the threat, how uncertain the future. In the understated terms of his opening lines, DeFoe quietly conveys a panic so general it hardly bears explaining; the widespread gossip, the frantic guessing as to where the disease had originated, and in the end that simple statement: all agreed it was come again.

That isn’t to say that we’re strangers to dread, in this day and age. Economic collapse, environmental disaster, social breakdown, religious fundamentalism; these are the real, believable dangers—in many cases, dangers that DeFoe could barely have imagined—of our age. And in a way, the raw simplicity of a true apocalypse is almost preferable. Because the terrors of our time are so nebulous, so hard to engage with, to even pinpoint. Who are the villains? Who the heroes? Does the threat even exist, or are we (as some insist) being lied to, by the wealthy and the powerful with agendas of their own? How can downfall be averted, if it can be at all?

There, then, is the appeal of post-apocalyptic literature, the reason for its flourishing, even decades after the Cold War that ushered the genre into the mainstream has ended. Because the problems in those stories seem so simple. In the end, calamity—nuclear war, plague, global winter—takes all of that anxiety and uncertainty away, and boils everything down to a single, very straightforward problem: survival, at any cost.

There’s a reason it’s called post-apocalyptic. The disaster itself almost doesn’t matter; it’s scenery, the reason why our heroes have to fight to survive. It gives us modern characters, but takes away the complexity of the modern age, and with it the protection of society. It gives us warlords and killers, striving to clamber to the top of the heap in the aftermath of the end. Nice, simple villains to despise and oppose, in a time of nice, simple problems to overcome. Even as we indulge ourselves in a world of our fears, we diminish it, make it into something to fight.

And it’s an injustice. How can you really do credit to a world of destruction, if you relegate the destruction itself to a backdrop? Take a leaf from DeFoe’s remarkable journalistic work! Show me that terror and that dread, that sense of the world come apart and the shock the survivors feel at suddenly losing everything they once depended on! It’s always been a core theme of the Afterblight books: Lee Keegan, Rob Stokes, the nameless hero of The Culled aren’t walking over the cooling body of a civilisation long-dead, but running through its death throes, trying to hold onto something not quite lost.

JOURNAL OF THE Plague Year rewinds the clock, takes us back through the first year or two of the Cull. Our heroes see a world still collapsing, new powers just beginning to rise; one actually watches the collapse from the outset, from the dubious safety of an orbiting space station. It shows us, if my authors and I have done our jobs right, that creeping dread, and rising panic, that DeFoe reveals in just a few bald words.

But it does more than that besides. I wanted to see the world. Four of the Afterblight books are set in North America; six in the former United Kingdom. We’ve heard hints of the rest of the world—a little about Japan, a hint of France and Germany, a suggestion of Russia—but (aside from Blood Ocean’s floating city in the Pacific) the stories themselves have largely stayed in the bounds of the Special Relationship. So I asked my authors: where else can you show me?

Malcolm Cross set himself two near-impossible goals. First, to tease together the many different snatches and glimpses of what the AB-virus actually is—by authors who, if we’re honest, aren’t biologists—and tie them into some coherent, plausible explanation (damned if I can tell you if he achieved it, since I’m not a biologist either, but I applaud the attempt). Secondly, he set out to tell a post-apocalyptic story set in the remote, clinical environment of the International Space Station; and this, I am proud to say, he delivered in spades. Orbital Decay is a tense, gripping thriller that somehow manages to be both claustrophobically isolated and terribly vulnerable to the chaos outside. Malcolm is a talented, hardworking young author who deserves to be better known.

I’m a bit of a sucker for old-school Ozsploitation stories—an Australian by birth, I watched a lot of really terrible movies as a teenager—and CB Harvey’s Dead Kelly brilliantly captures the mood of this very bleak, bloodthirsty subgenre. The wasted Outback always seemed, in these movies, packed full of leather-clad gangs, shooting and stabbing each other and doing awful things to each other’s girlfriends (it’s not, though; I checked), and “Dead” Kelly McGuire’s revenge drama is no exception. Colin got his break when he won the first Pulp Idol storytelling prize issued by SFX magazine and Gollancz, and it’s a real pleasure to publish him here.

I’m both a fan and a friend of Adrian Tchaikovsky, and I was thrilled when he offered to contribute to this omnibus, and intrigued when he wanted to step outside the safety of the Anglophone world and take us to his ancestral Poland. The Bloody Deluge not only forced me to go on Wikipedia and investigate the seventeenth-century war it’s named for (a fascinating period about which, I’m embarrassed to say, I knew nothing), it also perfectly captures the mood of hope amidst adversity at the heart of the series, and does it all with a distinctly European feel. He also offers a fresh, thoughtful take on the faith-versus-rationalism theme; delightfully, the staunchly atheist scientist running around after our heroine turns out to be not much less of a pain in the ass than his fanatical counterpart in the enemy camp.

Herein, then, three short stand-alone instalments in the post-apocalyptic world of the Afterblight Chronicles, shedding light on corners of the globe (and above it) you’ve never seen before. I hope you enjoy them.

David Moore, Editor

May 2014

ORBITAL DECAY

MALCOLM CROSS

CHAPTER ONE

&n

The transmission ended, leaving only a static-eaten silence.

Two hundred and fifty miles over Emily, and travelling at a little under twenty-eight thousand kilometres an hour, Alvin froze. He nudged the ham radio’s tuner just a hair, giving himself another second to delay before answering Emily’s question.

Kids were meant to ask ‘How do you go to the toilet in space?’ He had an answer for that. But this? All he had was the canned response Mission Control had given him.

“Well, Emily, before we were launched to Space Station, we were held in quarantine to make sure none of us were sick. But if we do get sick, we have the training and equipment to take care of each other, and if we need to we can even get advice from doctors on the ground. Thanks for your question, Emily.” He swallowed back a tense, tin-foil taste in the back of his throat. “We have enough time for one more question.”

A moment passed while microphones changed hands, and then a far more enthusiastic voice came across the radio. “Hi, my name’s Oliver and I’m ten years old and I want to be an astronaut and my question for Alvin is can you please tell us how to be an astronaut because I really, really want to be an astronaut!”

Alvin smiled. At least you could count on kids to want to be astronauts when they grew up, no matter what was happening on the ground. “Thanks, Oliver. What a great question. The most important thing is to find something you love doing, something you can practise until you become real good at it, but studying math and science help a lot! I’m sure your school or parents can help you look up more about that on the NASA website, and good luck with achieving your dream, Oliver.”

Oliver’s ‘thank you’ came through fuzzy, burned with radio hiss. It took just a nudge of the tuner knob to correct—Space Station’s orbit was fast and low, fast enough that radio signals between Station and ground receivers Doppler-shifted across radio frequencies depending on the alignment of orbit and Earth. Even corrected for, though, Alvin could hear the trademark bubble and pop of ground interference.

“I think that’s all we have time for. Station’s probably about to pass over the horizon from your perspective.”

“Well, thank you, Alvin, for talking to us down here at Bannerton Elementary in New Jersey,” one of the teachers said, so grave and formal he must have thought he was part of a historic broadcast to the moon landings, his voice torn to bits by static. “The Amateur Radio on the ISS program is a fantastic opportunity—”

“Thank you for the opportunity to talk to all the kids,” Alvin cut in. “Our transmit window’s closing, so this is NA-One-SS signing out. Good luck and God Bless to all the kids and staff at Bannerton Elementary. Out.”

No matter how hard he listened, adjusting the dial, all the static gave him were a few warbles that might have been a class full of kids yelling an enthusiastic ‘bye!’ at him. It had been a short window; from the ground, Space Station had streaked across a corner of the sky in just twelve minutes.

Alvin Burrows hooked his toes under the handrails on the surface he was treating as a floor, to anchor himself down while he turned the amateur radio set off. The silence in Zvezda, the Russian command module, was broken only by the ever-present humming of the airflow fans. As far as Alvin was concerned, after five months and one week in space, that just about qualified as pin-drop silence.

“Space Station, this is Houston. You’ve finished with the ARISS event?”

Alvin unhooked his toes and pushed away from the radio set, turning and twisting to re-orient himself toward the ceiling, and the communications panel. He leaned in to touch ‘transmit’ on the microphone. “That is correct, Houston. All went as scheduled.”

“Okay, Alvin. That was your last piece of volunteer work for today. For next week’s session you’re going to be in contact with the school in Reims, France. Any issues?”

Alvin shut his eyes and tried to picture the path that Space Station took over Earth. On a flat map it looked like a sine wave, bobbing North and South in long curves, although in reality it was just a regular orbit around the Earth, tilted away from the equator and making a full circle every hour and a half, while the world rolled sedately beneath. If France passed below, before that they’d either be coming in from the direction of Spain, or Britain... “Will the orbit let us fit in that private boys’ school if we start early? Have the session with them, then the French, one after the other?”

“I think so, Alvin. We’ll check into that for you. Any other business?”

“No.” Alvin stopped, staring at the photographs the Russians had stuck up on the bottom end of Zvezda. He was alone in the module right now, but it was part of the Russian living space. They, or their predecessors from earlier expeditions, had turned a wall into a shrine to rocketry, with photographs of Yuri Gagarin and other Russian heroes of their space program, but his crewmates Matvey and Yegor had colour photos of their children there, too.

Their children on the ground.

The taste of tin-foil in Alvin’s mouth was overpowering. He swallowed. “Actually, Tom, what’s the news on the pandemic down there?”

It was okay for the kids to ask, Mission Control had a rehearsed answer for them, but if Alvin asked about the pandemic there was always a thirty second pause before Tom transmitted an answer.

It wasn’t officially a pandemic, of course. Officially it wasn’t anything except this year’s bird flu outbreak. But whatever it was, officially or unofficially, the plague simply hadn’t existed when Alvin had launched on his Soyuz from Baikonur to Space Station. Now, people were infected everywhere from Alaska to Azerbaijan to Australia, and in the past few days victims were beginning to die. First, one or two; then dozens. Now? Hundreds.

It felt like Tom took far more than the usual thirty seconds to come up with an answer. “Not much different than in the news this morning. What’s the problem, Alvin?”

“I just don’t know what to keep telling these kids, Tom. They all want to know about the bird flu, whether we’re safe up here, if we’ve got a cure. They’re scared, and it’s heartbreaking, it’s just real heartbreaking, you know?”

Another thirty second delay ticked away, but it wasn’t Tom’s fault. Tom was another astronaut, assigned as CAPCOM on one of the communication shifts from Mission Control at Houston. He was older, though Alvin knew him well on a personal basis. Tom invited him over to barbecues and church fairly regularly, even though Alvin was still fresh blood, this his first mission. Hell, Marla—Alvin’s wife—traded baking recipes with Tom’s eldest daughter. Tom Rawlings was good people; Alvin trusted Tom. But that thirty-second delay put a sick, half-electric tinny taste down the back of Alvin’s throat.

“Well,” Tom said, “if necessary we can cancel some of the amateur radio sessions until the pandemic settles down and things start cooling off.”

“I’m coming home in three weeks, Tom. There aren’t that many ARISS sessions left.”

“Three weeks is a long time. I’m sure we’ll start hearing some good news about all this before the end of the week.”

Now it was Alvin’s turn to remain silent for a stunned thirty seconds. He shook his head slowly. “Well, I hope so, Tom. I guess that about does it.”

“Okay, Alvin.” No delay at all, now. “Once again, thanks for volunteering some of your free time. We all appreciate it.”

“No problem, Houston. Station out.”

Giving up free time was a big deal. On Space Station, free time meant time to clean, eat, and sleep. Thankfully, so far as sleep went, Alvin had found himself needing less and less since coming up to Station. His usual seven hours a night had dwindled to six, then gradually to five and a half. He hadn’t lost that last half hour of sleep a night until the pandemic had started.